February 23rd, 2022.

Welcome to our ‘Fresh Stock’ update – these items are fresh to our stock , and fresh to this website.

Today it’s some Wonderful Worcester.

Founder of Worcester Porcelain

Worcester Porcelain Museum;

Dr Wall, or ‘First Period Worcester’, is the earliest period of this important English porcelain maker. Dr John Wall was a fascinating 18th century Gentleman, a practical doctor who helped found the charitable hospital at Worcester, becoming wealthy and well-known in the process.

In 1751, along with William Davies and 13 other businessmen, he established the Worcester works on the banks of the River Severn, Worcester. Davies was an apothecary, not far removed from alchemy in the mid-18th century, and actively experimenting in the quest for a porcelain body. Together with Wall, and the help of the group of investors, the distinct Worcester porcelain body was developed.

There were many other attempts at making porcelain in England at this time. Bristol had a porcelain factory, and Chelsea and Bow were active in London, while Derby also had a porcelain works. Liverpool, Lowestoft and Bristol followed soon after in their respective cities. 60 miles from Worcester, Caughley made almost identical wares (before the age of copyright…). The pottery makers of Staffordshire soon began their own porcelain production, and so there are quite a number of makers of porcelain in England in the last half of the 18th century.

Confusingly, some of these other makers used the same ‘C’ crescent mark as Worcester. So how do we tell Worcester from the rest? A simple answer may be ‘Quality’. They always had a high standard, at least once they worked out how to consistently produce the same results from their kilns. But many other makers also produced high quality wares, and the decoration is often very similar, following the demands of taste. Without copyright, it was easy to copy a popular design.

The answer to identifying early Worcester is the body. They had developed a soft-paste, or artificial porcelain. Unlike the Chinese – and the Continental porcelains, like Meissen – it lacked a vital ingredient found in ‘true’, or hard-paste porcelain. This ingredient was responsible for the stability, or hardness of the body, and this in turn meant it was more durable. Especially important considering the teawares that came to be a major part of their business; if a teapot cracked when hot liquid was poured in, it was not good for business – and this was what often happened to the likes of early Bow and Derby. Worcester prided itself in the ability to withstand hot water ‘shock’ – but was resistant, not crack proof. We do see an awful lot of Worcester teapots with classic spreading hot-water cracks.

One of the 15 initial partners in the Worcester concern was Richard Holdship. He was somehow aware of a struggling porcelain manufactory at Bristol, the works of Benjamin Lund. This had begin in 1749, with the granting of an exclusive licence to mine ‘soaprock’ at the Lizard, Cornwall. When this special ingredient was combined with their clay, Lund’s Bristol porcelain had a different quality to other English porcelains of the period. The soaprock unified the body, allowing it to distribute heat better, for example when boiling water was poured into it. Lund produced a limited line of products for a limited time, and by 1751, was in financial strife. Holdship was able to come in and buy-out the works, including the equipment, workmen, even Lund himself came to Worcester to the new works there. Most importantly, the Worcester firm now had the rights to the soap-rock of Cornwall, and added to their clay, produced the fine body we are used to with 18th century Dr Wall Worcester.

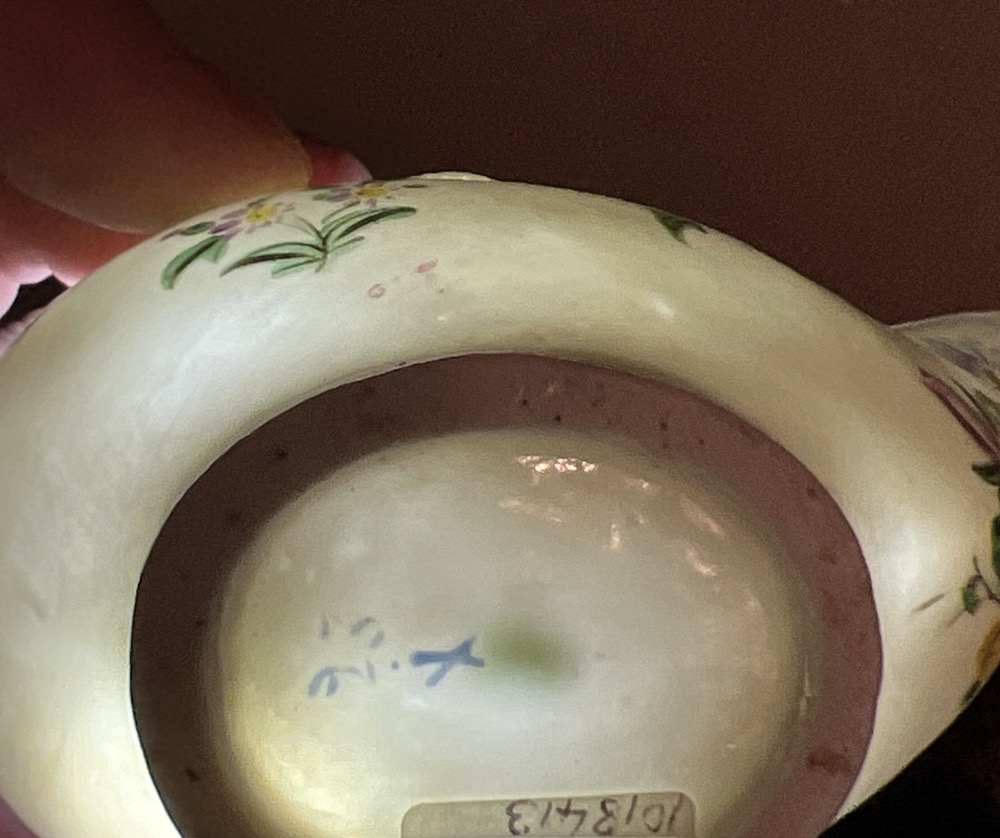

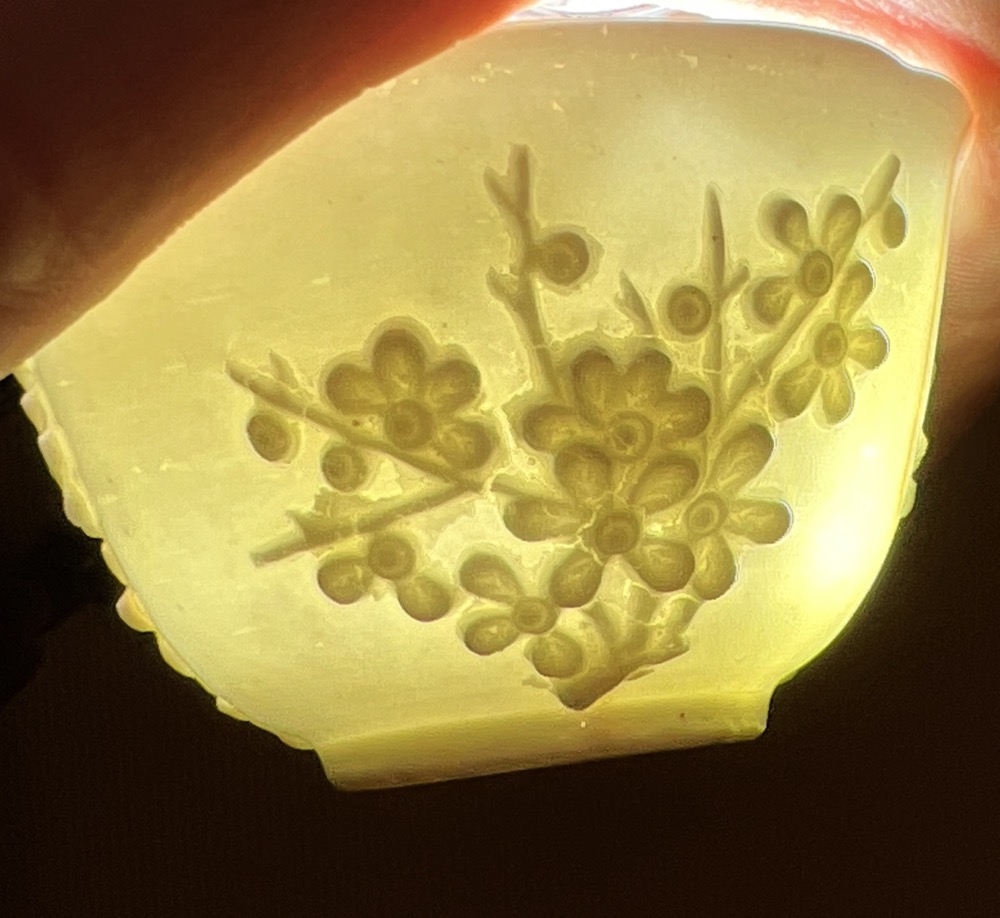

So how do we identify this Worcester body? A very simple process: hold it up to the light!

A porcelain body by definition is translucent. This means the light is able to penetrate into the structure of the fired clay, and some finds its way through. When it strikes the minerals inside – such as the soap-stone – part of the light spectrum will be absorbed, with the remainder of the spectrum escaping to the viewer’s eye, resulting in a certain colour tone. In the case of Worcester with the soap-stone, it’s a greenish tone we look for.

Caughley Translucency c. 1780

Bristol (Champion’s) Translucency c. 1775-80

Chelsea Translucency c. 1755

Bow Translucency c. 1755

This of course isn’t definitive test – there are variations, decoration changes things, and other factories could also produce green-tinged bodies. But combined with visual cues like patterns and shapes, spotting Worcester becomes a much simpler task.

This week, our Fresh Stock release has a series of superb Worcester ‘Saucer Dishes’, painted in the various Rococo patterns of the later 18th century. Literally a dish-sized ‘saucer’ shape, there was one, or sometimes two included in a tea service, intended to hold the cake or nice little knibbles the ‘Lady of the House’ was to serve when offering tea in the fashionable sitting room to visitors.

The ‘Marriage’ pattern is beautiful, with hidden symbols of Cupid amongst the flower sprigs. Apparently George III liked this pattern, and had a service made for Kew House. The older tale was it was to celebrate his marriage, although there are no records as such; however, the name ‘Marriage’ for the pattern is totally appropriate considering the hidden symbols of a bow, a quiver, and a lover’s knot.

The ‘Powder Blue’ example is fascinating, in that the flowers are lavish and flamboyant – but the fan-shaped reserves are outlined in a simple straight line of gold, with no scrolls to be seen. This reflects an earlier period, when Chinese porcelains from the Kanxi reign were coming into Europe with similar decoration. The ‘powder-blue’ ground is literally created as it sounds – a powder of blue cobalt pigment is blown onto the piece, which is treated with an oil to make it sticky; where the white panels are to be, a paper stencil cutout is attached. Once fired, this leaves the white panels to be painted by the factory artists. in the case of this plate, the artist was very good – the same hand is at work on a jug in the Zorensky Collection, along with the very stylish flower sprays. This gilding is the thick & rich ‘honey gilding’ , once again created exactly as described – honey is used to suspend the gold and apply it to the porcelain, where it burns off & leaves the gold in place when fired.

The example with the urn in the centre is Dr Wall Worcester at its best. This fluted shape is known as the ‘French’ shape, and was very popular for tea wares. The combination of the central flower-clad urn and the colourful swags of flowers hanging from suspension amongst the rich gilding around the rim is enhanced by the startling splash of turquoise ‘caillouté‘ work, a French word meaning ‘pebbly’. It’s based on the luxurious Sevres imports of the time, and the whole look & feel of these flamboyant pieces deserve their ‘French’ title.

Enjoy!

Remember, we post world-wide at the most reasonable rates – ask for a quote.

Fresh Worcester

-

Worcester fluted coffee cup & saucer, daisy pattern, c. 1770$980.00 AUD

Worcester fluted coffee cup & saucer, daisy pattern, c. 1770$980.00 AUD -

Dr Wall Worcester ‘French’ shape saucer dish with central urn with turquoise frame, c.1770Sold

Dr Wall Worcester ‘French’ shape saucer dish with central urn with turquoise frame, c.1770Sold -

Dr Wall Worcester scalloped edge plate, ‘wet blue’ border with gilt, flower spray, c.1770$1,380.00 AUD

Dr Wall Worcester scalloped edge plate, ‘wet blue’ border with gilt, flower spray, c.1770$1,380.00 AUD -

Flight Worcester plate, gilt wreath & blue band border, C.1790$540.00 AUD

Flight Worcester plate, gilt wreath & blue band border, C.1790$540.00 AUD -

Flight Worcester plate, gilt wreath & blue band border, C.1790$540.00 AUD

Flight Worcester plate, gilt wreath & blue band border, C.1790$540.00 AUD -

Worcester cup & saucer, swags of flowers & urn, c. 1770$1,250.00 AUD

Worcester cup & saucer, swags of flowers & urn, c. 1770$1,250.00 AUD -

Dr Wall Worcester scale blue plate, lobed rim with flowers in panels, c. 1770$795.00 AUD

Dr Wall Worcester scale blue plate, lobed rim with flowers in panels, c. 1770$795.00 AUD -

Dr Wall Worcester saucer-dish, powder blue with flowers, gilding, c. 1768$1,250.00 AUD

Dr Wall Worcester saucer-dish, powder blue with flowers, gilding, c. 1768$1,250.00 AUD -

Flight Barr & Barr cup and saucer in rich Imari, c.1820$585.00 AUD

Flight Barr & Barr cup and saucer in rich Imari, c.1820$585.00 AUD