Welcome to our latest Fresh Stock release. There’s quite a range of Fresh items to browse….

Here’s our new way of browsing: enjoy!

Our Latest stock releases.

To see these items first, join our email list.

Welcome to our latest Fresh Stock release. There’s quite a range of Fresh items to browse….

Here’s our new way of browsing: enjoy!

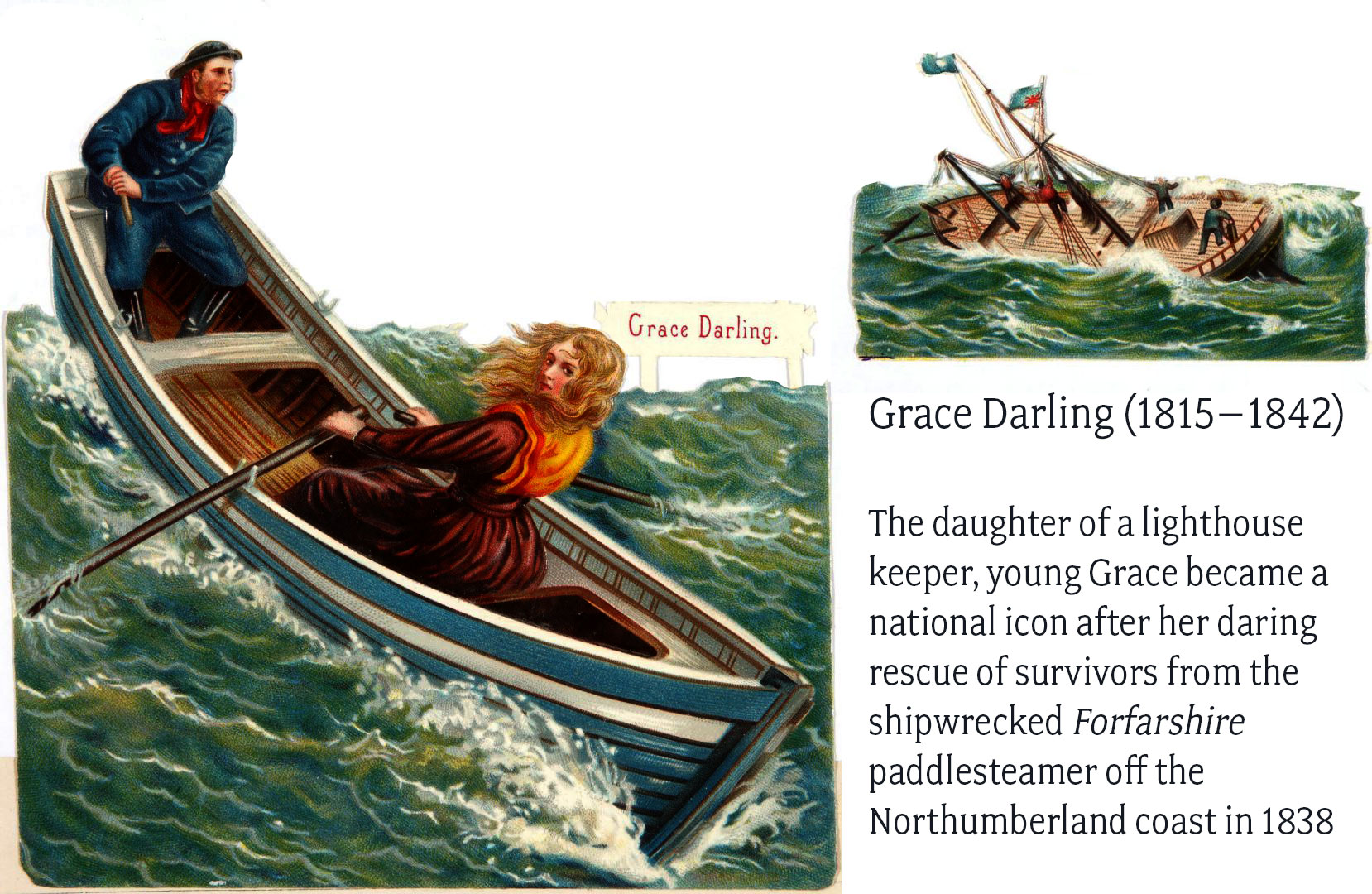

This charming Staffordshire figure commemorates one of the celebrated heroines of the Victorian age—Grace Darling (1815–1842). The daughter of a lighthouse keeper, Grace became a national icon after her daring rescue of survivors from the shipwrecked Forfarshire off the Northumberland coast in 1838. Braving fierce seas in a small rowing boat with her father, she helped save nine lives, against all odds. Just a few years later she died of tuberculosis.

Her youthful bravery captured the public’s imagination, inspiring poetry, paintings—and popular ceramic tributes like this figure.

Grace’s story epitomised Victorian ideals of courage and virtue, making her a popular subject for ‘mementos’ – including children’s books, several ballads with illustrations, and of course the Staffordshire potters were up with the trend, producing these charming figures for the domestic mantel shelf.

There’s probably a print with the scene depicted, as yet not identified.

What makes this example unique is…. she’s alone her boat! Her father should be in there with her, seated opposite. In this case there is a white-glazed area, which closer examination shows to be a pair of legs and nothing else! It looks like the wave that has almost swamped the small lifeboat the brave girl is rowing has swept her father away, leaving only his trousers!

What has happened is a firing flaw in the factory – he’s come off in the initial firing – or the person responsible for placing him into the original clay moulded blank has missed this small additional moulded piece – so that when it came to be glazed, it was simply smoothed over and glazed, and never painted.

Surely a unique example of a rare figure type!

Welcome to our first ‘Fresh Stock’ for 2025.

Chinese bronze censors, Ming Dynasty, 16th-17th Century

We have a lot of splendid items to prepare for you, and will be releasing them over the next few weeks in groups of similar items – let’s call them ‘mini-Exhibitions’.

Starting with….. Asian.

Chinese, Japanese, Burmese, Sri Lankan…. there’s a great variety of cultures represented here.

Thee miniature masterpieces are collectively known as ‘opium’ weights, as that was a common use for them in their countries of origin in South-East Asia – but they were used as the measuring weight for any other spice or item that needed weighing. The most commonly seen is a very cute crested duck – represented in this group by the rarely seen minute example, just ##mm tall…. The majority of these examples are a mythical ‘Lion’ creature, with four legs like a horse, a head that almost has a beak, and a wild main and tail – each also featuring a broad beaded necklace. Rarest in this group is a tiny creature we have called a ‘dog’ – but it may well be something else.

A fine selection of interesting Chinese & Japanese items come from several local collections. One in particular is significant, as it was accumulated in England in the 1960’s before the (now elderly) owner migrated to Australia. This provenance helps us be certain of the authenticity of the items; the copies in the mid-20th century were not as refined as those that are flooding the market today, and therefore more obvious. The downside is there are a lot of damaged, but genuine pieces…. but these are in themselves excellent inexpensive ‘Reference Study Pieces’.

These flamboyant beasts are from Sri Lanka, in particular the city of Kandy.

They represent the annual ceremony known as the Esala Perahera, which is one of the most vibrant and sacred festivals in the country. Celebrated for centuries annually in July or August, this grand procession is dedicated to the Sacred Tooth Relic of Lord Buddha, housed in the Temple of the Tooth Relic (Sri Dalada Maligawa).

The event blends spirituality and culture, with the stars being a mesmerizing parade of elaborately adorned elephants, traditional Kandyan dancers, fire dancers, drummers, and flag bearers. The air is filled with the rhythmic beats of drums and the glow of flickering torches as the procession winds through the city streets at night. At its heart, the largest and most elaborately decorated of the elephants has the honour of carrying the revered golden casket housed in a pagoda on its back, which has inside the Buddha’s Tooth Relic. These silver-clad jewel embossed beauties are a small reminder of an unforgettable experience.

More Elephants!

…. and still more Elephants!

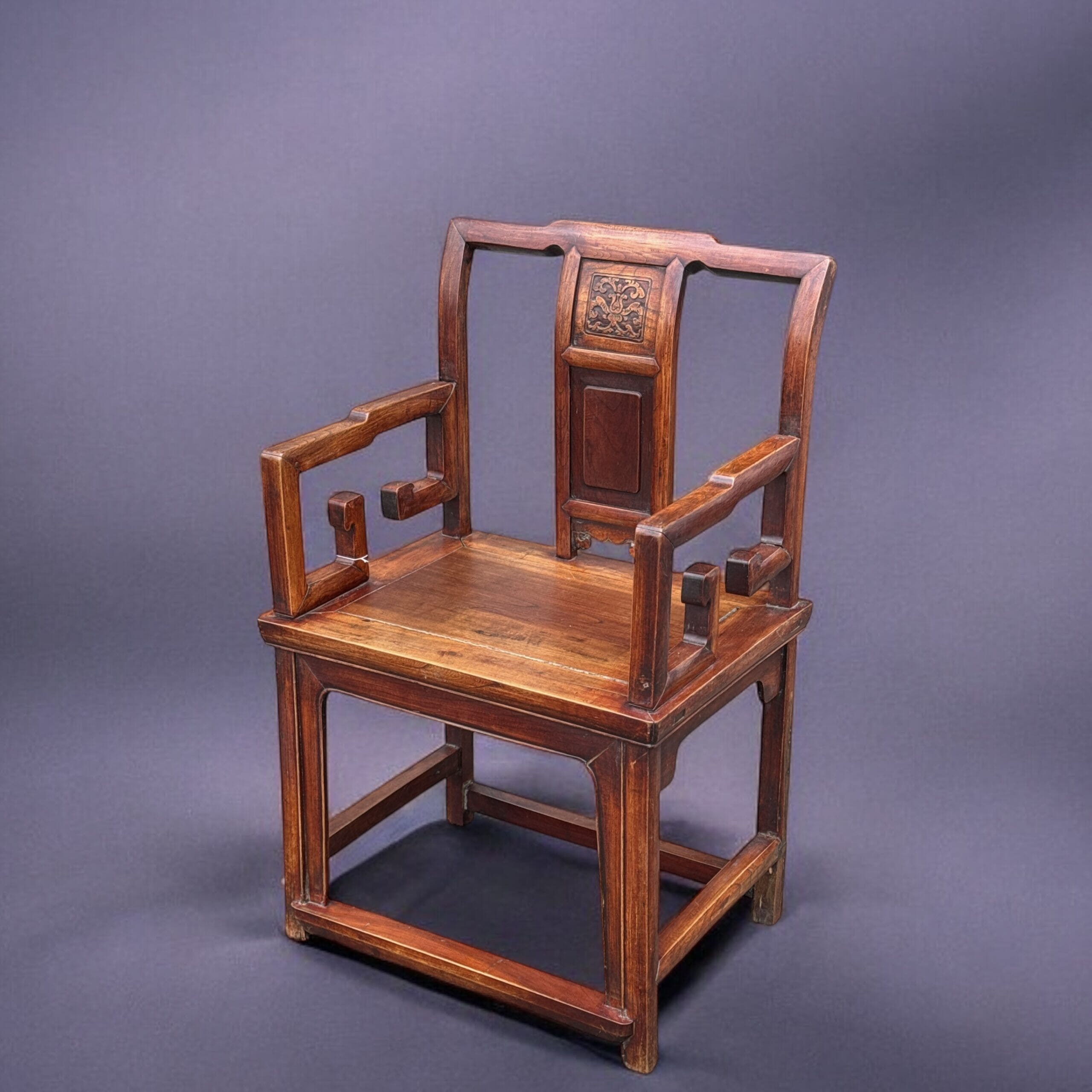

There’s a few houses-full of furniture fresh to stock at Moorabool Antiques. View the latest here:

It’s been a good while since our last ‘Fresh Stock’ – so here’s a bumper issue to make up for it!

You’ll find a fine and varied selection, from Georgian Furniture to fine 18th century Porcelain, Australian Pottery, a host of Candlesticks, and interesting Artworks.

Enjoy!

There’s a fine selection ‘Premium’ rarities Fresh to stock. Here’s a sample: see them all on their own page here >

Some small precious items, perfect presents…..

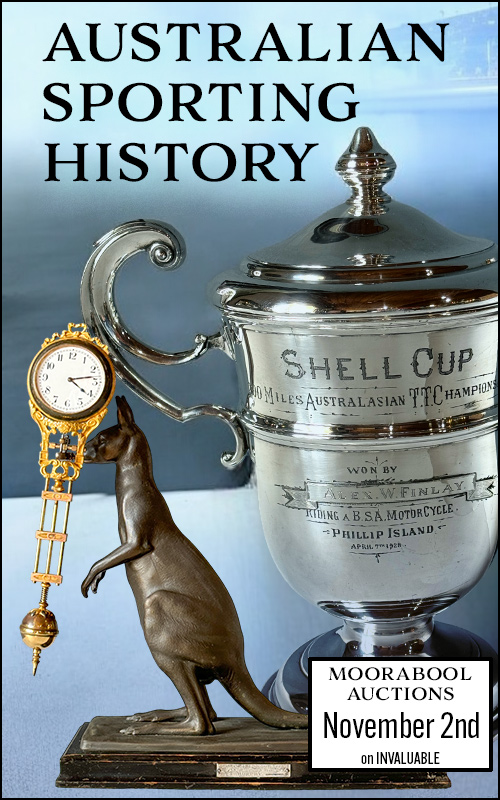

NOVEMBER 2nd – live on Invaluable

Our Auctions continue to grow in content and audience – a terrific way to sell if you are thinking of it, and the perfect place to buy at great prices.

Our next sale is currently being prepared, and features some Australiana rarities, including:

Australian Grand Prix prizes – from the FIRST Australian ‘TT’ Grand Prix, held on Phillip Island in 1928, we have the ‘Shell Cup’, a giant silver-plate affair, won by Alex Finlay on a B.S.A. bike ‘just taken out of the box’!

Rare original German bronze kangaroo ‘Mystery Clock’, 1st prize Time Trials won by Les Murphy in an MG-P in 1935.

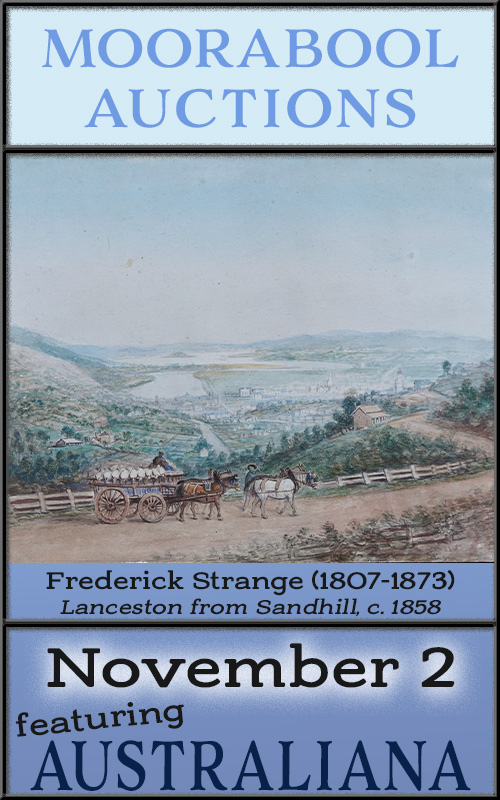

Artworks include a ‘View of Launceston’ watercolour by the extremely rare convict artist Frederick Strange, c. 1858, from the personal collection of Clifford Craig, the original researcher of this interesting colonial identity in the 1960’s.

Also Fresh to Market is our recently identified George Peacock oil, ‘View of Sydney Harbour from Carrara House’, circa 1855. We have pinpointed the exact place Peacock painted this view from, with Carrara now being known as ‘Strickland House’, the gardens now public parkland along the waterfront of Vaucluse.

Several desirable oils by W.D. Knox come from the descendants of this fine Australian artist, fresh to the market for the first time.

Plus more….. an email will notify all subscribers when the catalogue is uploaded & ready for exploring.

Welcome to our selection of ‘the Best’ for the end of 2024.

Some stunning rarities have come to us recently, with many local high-quality collections being dispersed.

Enjoy your browse through the following Premium items – with more items being prepared for the near future.

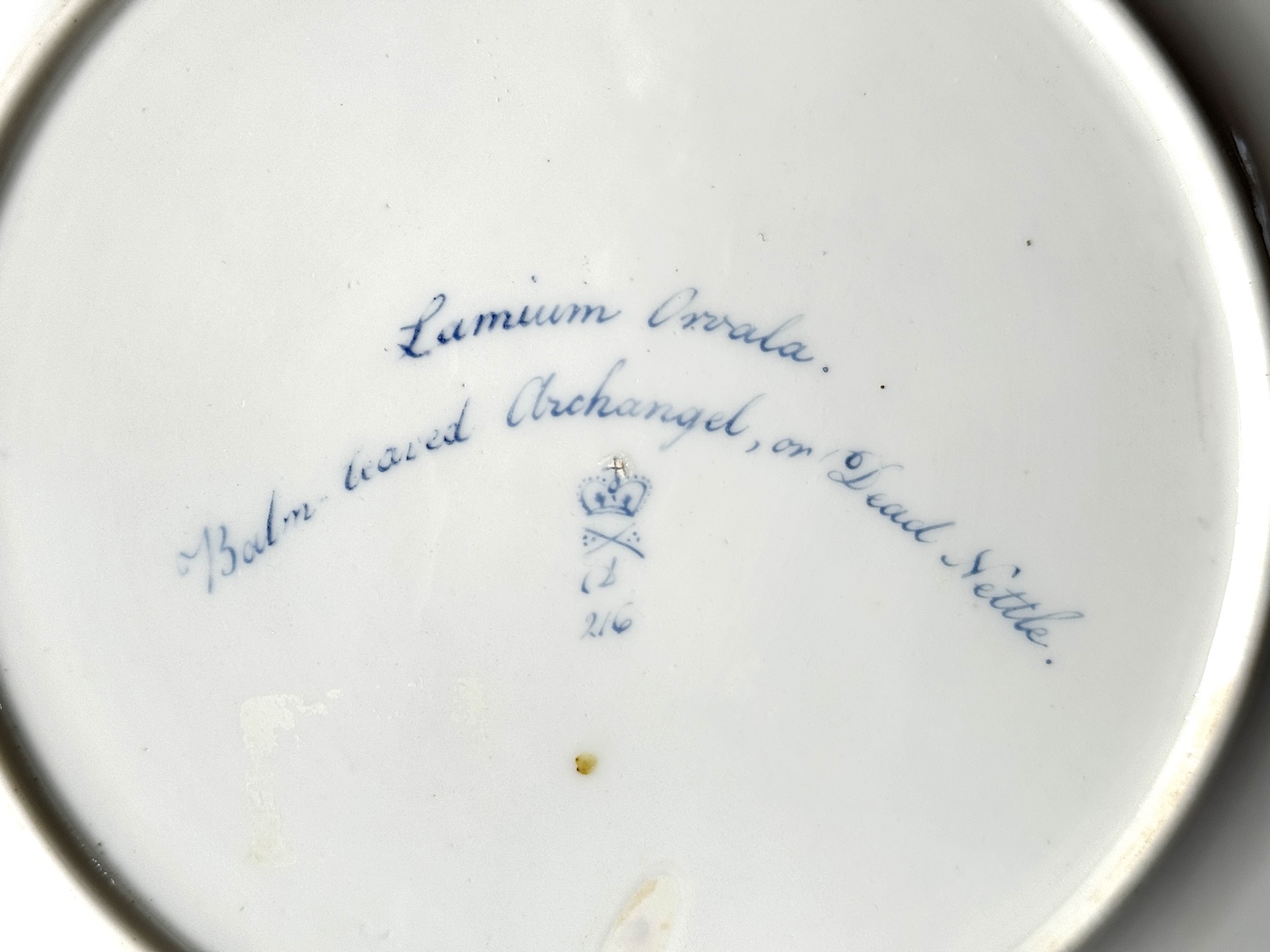

Quaker Pegg – “Balm-leaved Archangel” c. 1796

From the English Derby factory comes a piece by their finest botanical artist, William ‘Quaker’ Pegg.

William Pegg, known as Pegg the Quaker for his personal beliefs, was born in 1775, the son of a gardener, and came to be regarded as one of the finest painters of flowers on porcelain of all time.

He came to Staffordshire – ‘The Potteries’ – aged 10, in 1788. He was apprenticed as a ‘china painter’ – and would have been tasked with the monotonous jobs like ground colours and gilding rims. He collected prints and learnt how to draw, concentrating on plants – hardly surprising considering his father’s profession.

He had heard John Wesley preach in 1786, and had joined the Quaker ‘Society of Friends’ who followed the thoughts of men like George Fox – “…Thou shalt not make any graven Image, or simulate any figure… male or female… winged fowl… creeping thing… fish… by the express command of God”. He took this to heart, and flowers became his focus.

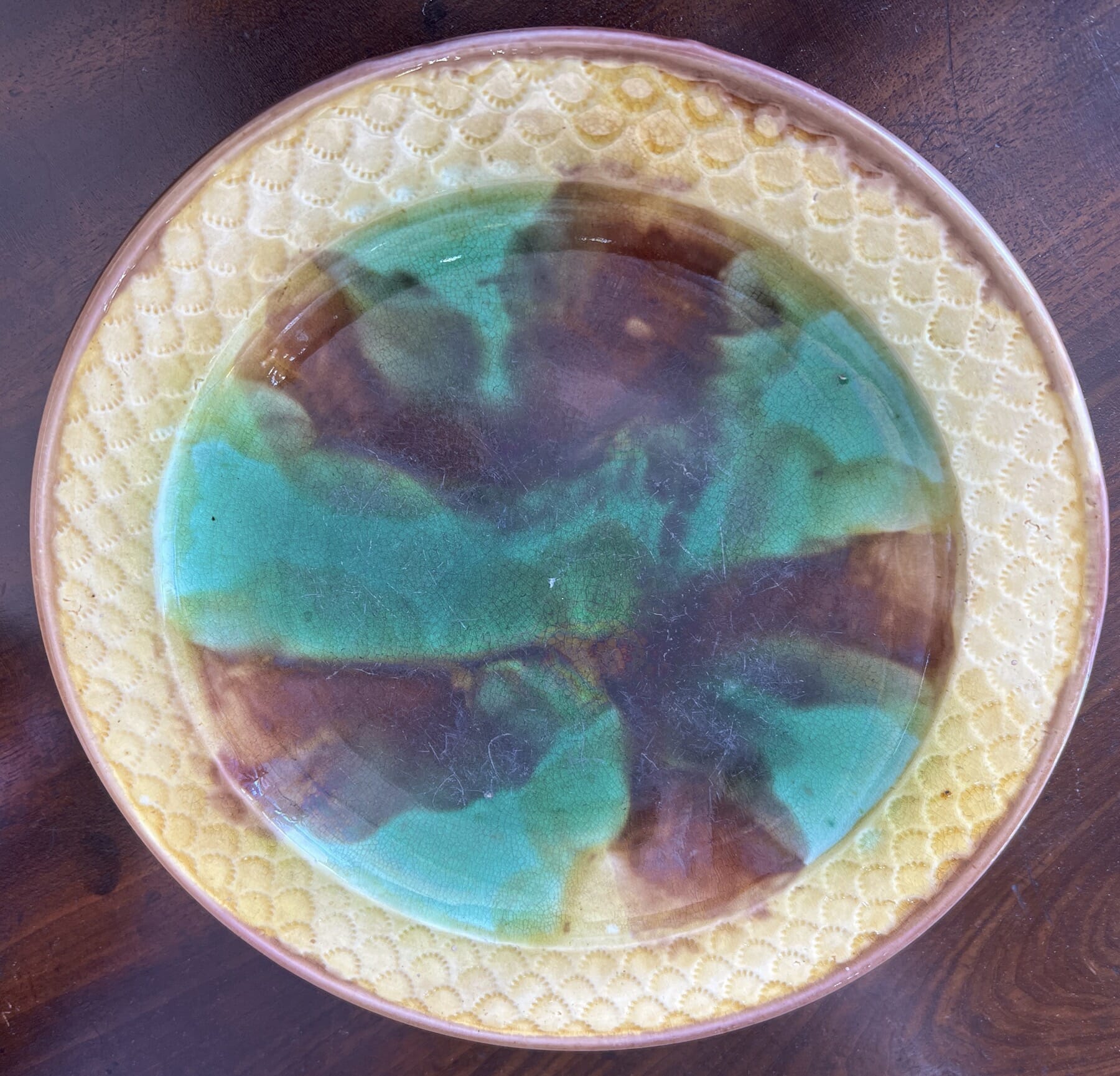

This magnificent yellow-ground plate has a large, accurate specimen to the center. The back has the title in blue – in the distinct script attributed to Pegg’s hand- “Lamium Orvala / Balm-leaved Archangel, or Dead Nettle. “

This was taken from the most current horticultural publication of the period, ‘Curtis’s Botanical Magazine’, plate 172, published in 1791. Other examples are dated to circa 1796, early in Pegg’s botanical works.

There’s a number of ‘Delightful Derby’ season figures, illustrating the evolution of their plinth styles.

A stunning silver & etched glass claret jug is Fresh to Moorabool. The body is decorated with blackberry canes, flowers and fruit – which continues to the solid silver mounts, with a twisted cane and root as the handle. The result is a spectacular, useful piece of Art Nouveau beauty.

The marks on the piece indicate the components are actually made in different countries. The glass is French, marked for Verrerie de Sèvres – a glass works located on the outskirts of Paris. The silver is Austrian, made in Vienna by the master-silversmith firm, Brüder Franks, the Franks Brothers. It bears the mark of the company – ‘BF’ – and also a ‘winged hammer’, the mark of one of the brothers, Rudolf Frank. The firm was active in the latter 19th , early 20th century in Vienna, making high-quality pieces like this – although the combination of French Glass and Viennese silver is rarely seen.

While the Verrerie de Sèvres was founded during the reign of Louis XV, and located at the place named Sèvres, it was not part of the Royal manufactory, but an independent concern small size, making useful wares for the local market. This changed in 1870 with a new owner, Landier, who began the manufacture of lead crystal glass, and changed the name to ‘Christallerie de Sèvres’. In 1875 he took over an established glassworks in Clichy, enabling him to introduce new techniques of manufacture and engraving. The name was then added to : ‘Christalleries de Sèvres etClichy Réunis’. As the 1890’s began, they were engaged in the multitude of artistic glass styles, and some naturalistic forms were made. This was the beginning of the Art Nouveau movement, and they developed a splendid range of Nouveau taste designs using acid to etch the background of the vessels to give them a natural texture, reserving designs – such as the leaves on this piece – which were then further embellished. Some were mounted there in silver-plate; this example is rare, having solid-silver mounts.

The mark of ‘V / R’ ranking a sailing ship was used on these quality products from the 1890’s. The V and S are the initials of the firm; the ship is similar to the one found on the arms of the city of Paris, indicating its proximity to the ‘centre of culture’.

NOVEMBER 2nd – live on Invaluable

This is currently being catalogued, but will include over 300 items, with some absolute bargains –

and a number of major pieces of Australian Art & Historical Items.

Robert Prenzel 1866-1941 (German/Australian) – Pair of almost life-size Aboriginal portraits, signed & dated 1921

Includes two Convict artist works ‘Fresh to the Market’:

George Peacock 1806-1890? (English/Australia) – previously undocumented oil painting “Sydney Harbour from Carrara House, Vaucluse” circa 1855 .

Frederick Strange 1807-73 (English/Australian) ‘View of Launceston from Cornhill’ c. 1858 .

William Dunn Knox 1880-1945 (Australian)- previously unseen oil paintings from the Knox family collection including “The Hill”, “Haystack, Olinda”, “Farmhouse”, 1920’s-30’s.

Jan Hendrik Scheltema 1861-1941 (Dutch/Australian) – view in Holland, oil on canvas

Other Australiana includes an Invite to the opening of the 1st parliament, Exhibition Buildings Carlton in 1901; ‘The SHELL Trophy’ important large trophy for the 1st motorcycle Grand Prix to be held on Phillip Island, 1928; a 1935 bronze Kangaroo, used as a Car Racing Trophy 1st prize in Victoria, 1935; an Australian Sterling Silver Belt Plaque awarded to Nathan Ratcliffe of the Lockwood Farmers Cricket Club, by Melbourne silversmith William Edwards, 1860; attributed to William Edwards, a large silver trophy cup circa 1870 awarded by Alfred Felton at his Melbourne Glass Bottle Works in 1900; plus much more – Uranium Glass, Rare Books, Coins, etc. etc. ……..

Catalogue is being prepared, a future email will alert you when it’s all ready to browse.

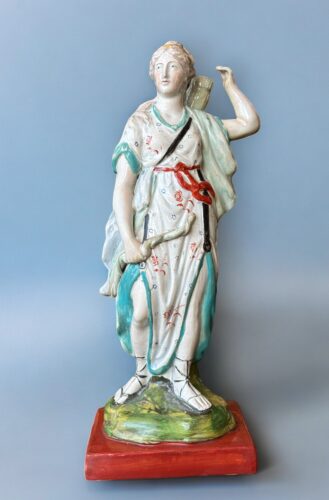

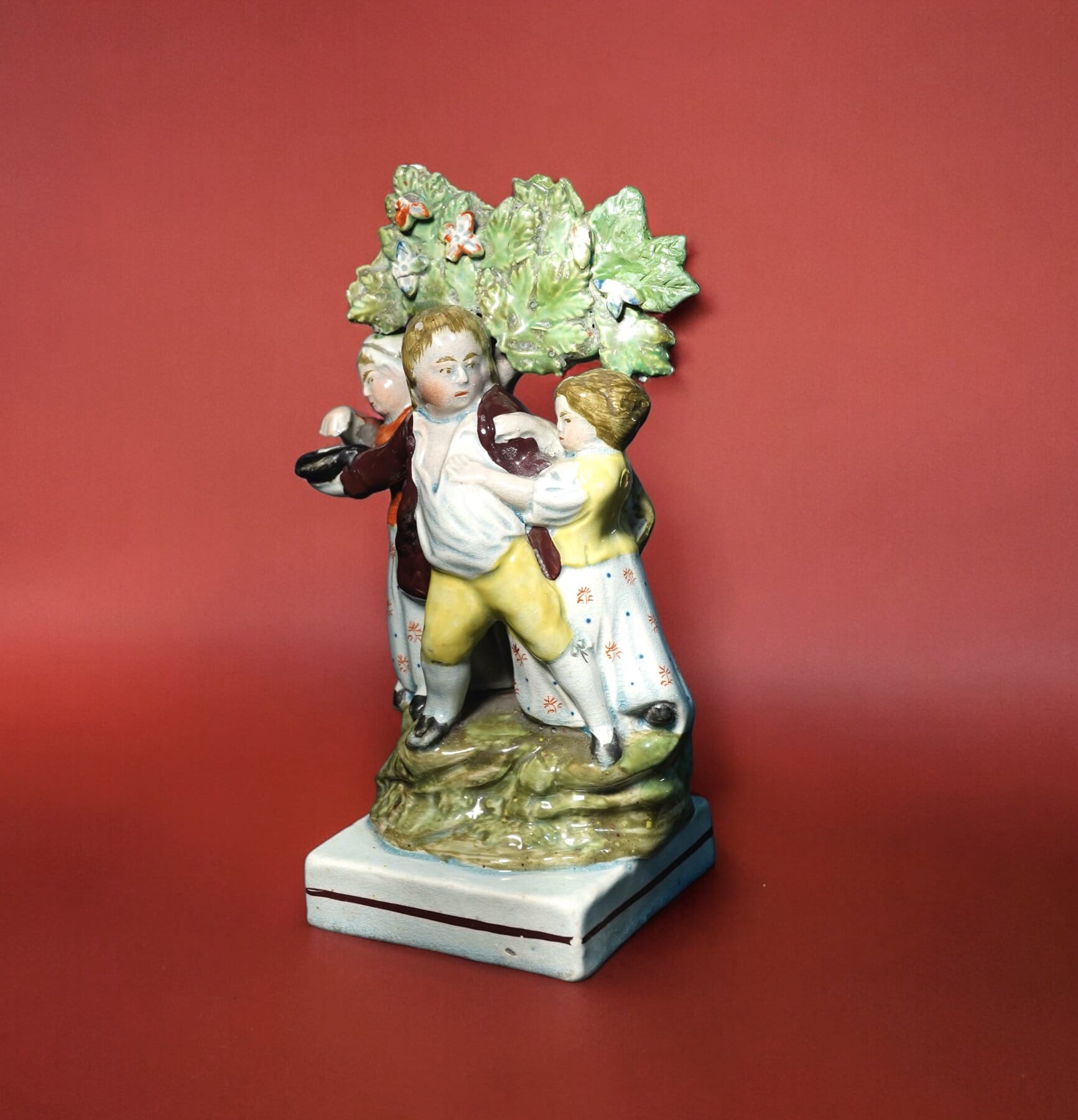

Moorabool has a fascinating group of Derby ‘Seasons’, modelled as children with their respective attributes.

left to right: Spring, Summer, Autumn, Summer, Spring. We have no Winter….

They make for an interesting study, and show the development of the classic rococo-based Derby figures of the latter 18th century.

The earliest version appears during the mid-1750’s, belonging to a group of distinctly modelled figures that are often decorated in a muted pallet of colours, known as the ‘pale-family’. These appear with a flat slab base, and the modelling is a little stiff. Note this example has lost his hand & the wheat he holds in it.

Circa 1756

‘Summer’, Pale Family type, 1756-59. ref. Bradshaw ‘Derby Figures’ p72.

This example, in stock at Moorabool, is late in the ‘Pale Family’ period, or the very beginning of the next period, the ‘Patch Mark’ period, c. 1759-69. The base has an early, rarely-seen rococo scroll moulding, of quite flat form without piercing. The colours are the type used in the 1760’s.

Circa 1760

This example, also in stock at Moorabool, shows the latter 18th century style of Rococo scroll base, with scrolls forming feet on which it rests, and a pierced panel to the center.

This boy is representing ‘Spring’, with a garland of flowers.

Circa 1770

This example, also in stock at Moorabool, shows the latter Rococo scroll base, with scrolls forming feet on which it rests, and a pierced panel to the center.

Once again ‘Spring’, with a garland of flowers. Interestingly, he is not recorded in Bradshaw (Derby Figures), who has only a set of 4 ‘Adolescent Seasons’ listed that are all girls; these boys appear in the earlier sets and were obviously continued into the latter 18th century – it’s a puzzle why he has failed to record them.

Circa 1780

Of course, other factories were actively making ‘Seasons’, with a particularly lovely ‘Spring’ by Bow being a recent addition to Moorabool.com’s stock:

Bow figure of ‘Spring’, with distinct blue enamels, c. 1765. See her here>

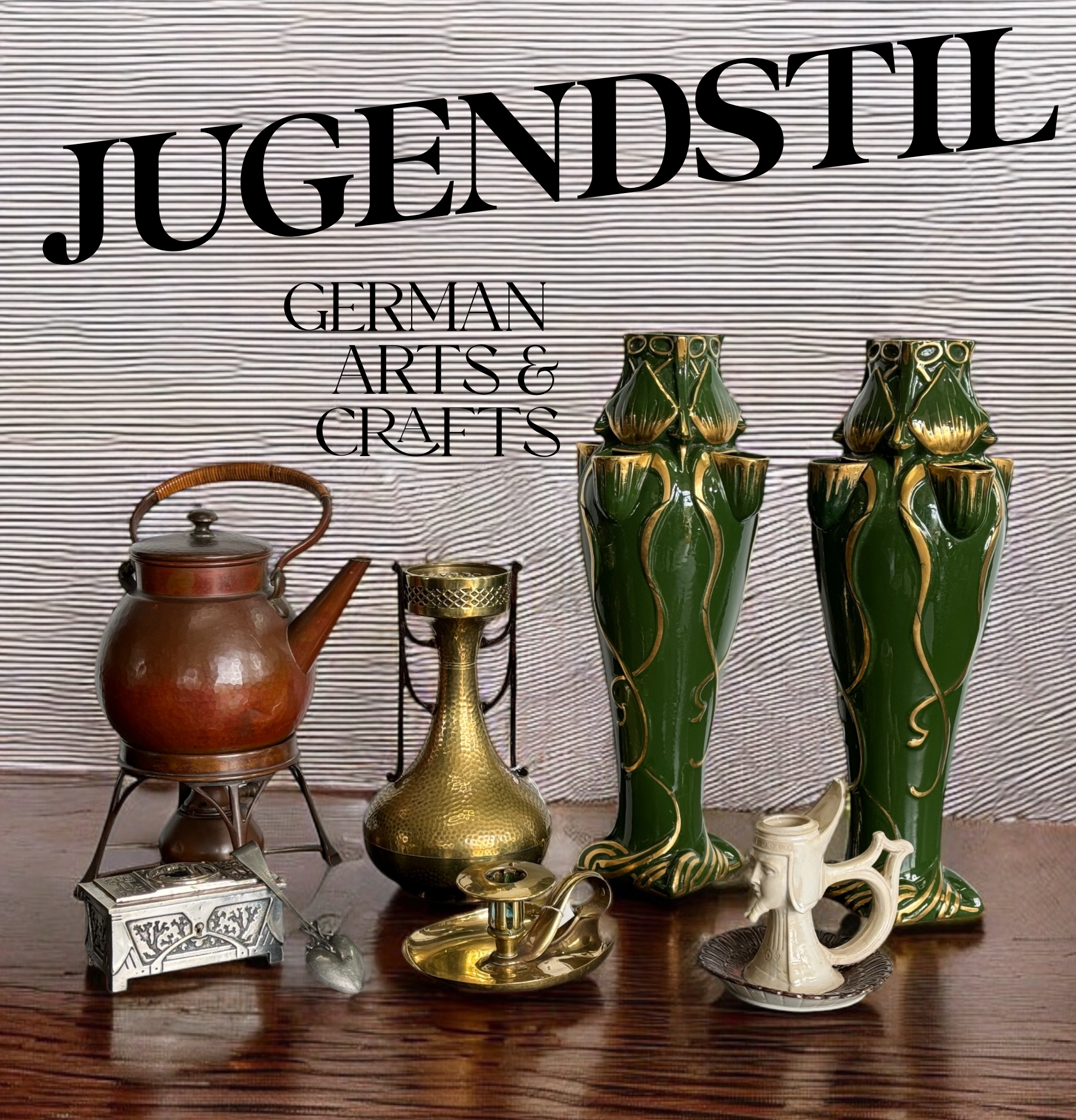

A fine selection of ‘Arts & Crafts’ has just been posted on Moorabool.com . It’s an interesting survey of the late 19th- early 20th century designs that were a reaction against the overly ornate – and predictable – designs of Victorian England. Often borrowing & intermingled, the French Art Nouveau aesthetic blended with the German/Austrian Jugendstil (youthful-style) and even had a major impact on Australian products – although it did take some time to reach us ‘down-under’ !

The rarest, and most dramatic is a pewter teaset & a tray, made to the patterns of Archibald Knox (1864-1933) while he worked at the London workshops of Liberty & Co in the first years of the 20th century. Branded ‘Tudric’, the designs are extraordinary, a mix of Art Nouveau and Celtic, with the simplicity of Christopher Dresser and the design principles of the Arts & Crafts (ie rivets attaching handles evident to show how it is made – although in this case, they are only decorative!). The set was in the possession of a Geelong family since around the time of WWI, and so probably since new; however, the tray is design no. 42, while the teaset is design no. 231, each of which had its own tray/teaset designed alongside. The matching of these two pieces is probably a case of a retailer putting the two together to sell them – they do look rather splendid! We have split them again for sale.

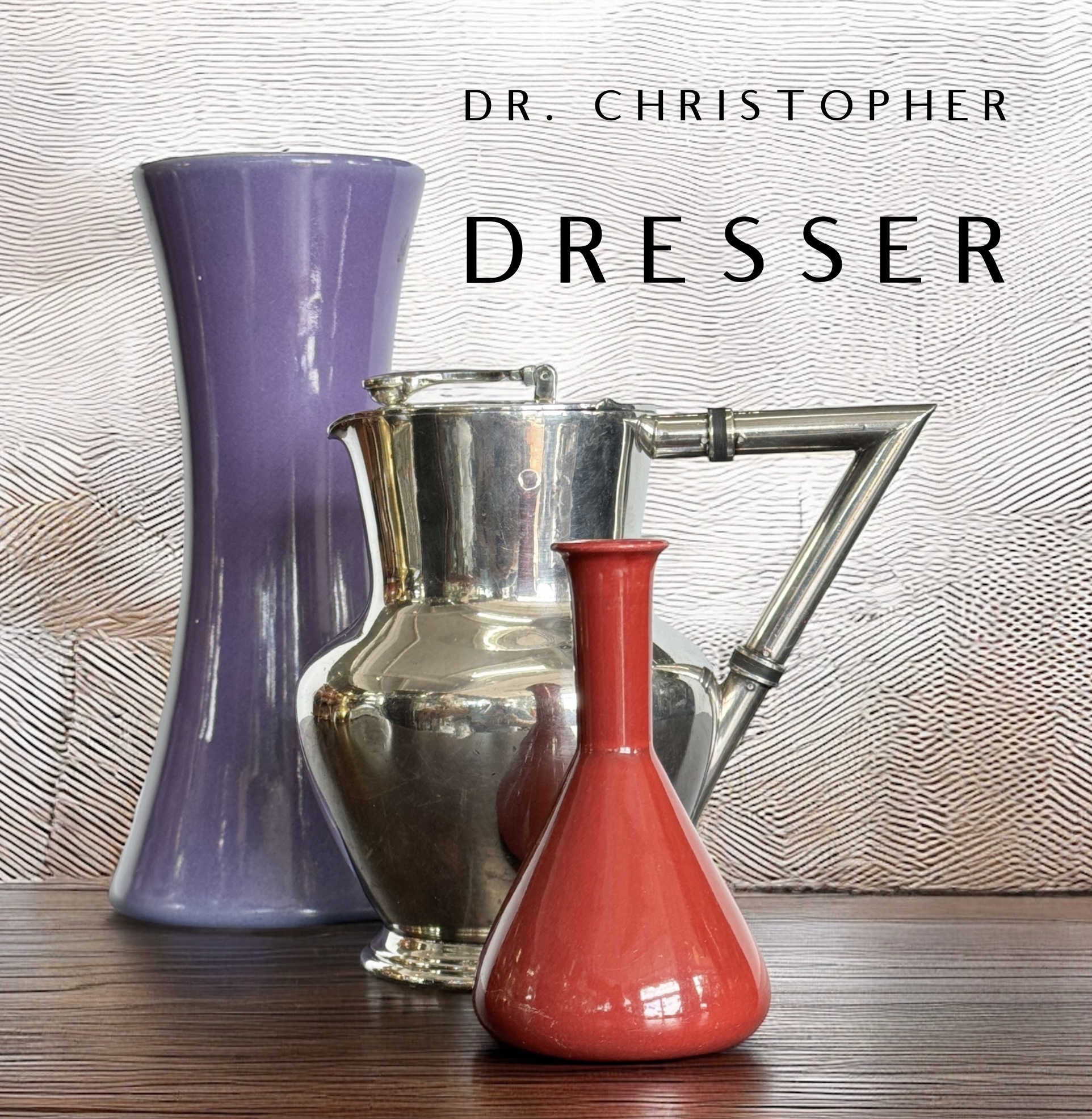

Dr Christopher Dresser (1834-1904) is represented with an interesting ‘modern’ design jug with dramatic angular handle that was years ahead of its time, made by Birmingham silversmith . There’s also some pottery that clearly was inspired by his designs, which were admired & copied across many manufacturers.

Dr Christopher Dresser was a visionary, and as a designer, was far ahead of his time. The pieces illustrated here look 1920’s, but were sketched by him and made in small quantities by numerous firms in the 1880’s; it just took the design world another 40 years to catch up!

A selection of German / Austrian pieces conform to the Jugendstil (‘youthful-style’) movement. Closely related to the English Arts & Crafts, and the Art Nouveau movement, it was centred in Germany/Austria/Belgium, and lasted roughly 1895-1910. The name comes from an art magazine promoting youth culture, and it was an important part of the emergence of the Secessionist movement – the rejection of ‘legacy art’, ie the classical world, and the invention of a fresh style. This definition applies to the ‘fine arts’ of sculpture and painting, but with the items we are displaying here, clearly defines useful household items as well.

The Australian Silky Oak sideboard is being used for its correct purpose – to display the wonders of the Arts & Crafts period!

A flamboyant pair of large French vases are pure ‘Art Nouveau’ – and have 5 spouts to the top. Marked with a battle axe, they are from the firm of Gustav Asch in Tours. Most of their products were looking back to the traditional Sevres products, or in the ‘belle époque’ style that was so popular with the Victorians – making these Art Nouveau examples quite rare. Circa 1895-1900.

Stylish Swedish ‘Arts & Crafts’ pewter spoon, by Frans Santersson, Stockholm circa 1905.

The heart-shape bowl is engraved ‘Stockholm’, and the handle junction with the bowl is extraordinary – with a looping intertwined designed that looks like a plant shoot.

This curious small vase is decorated in slip colours with a frieze of flowers and their stalks. Looking a little like the English Moorecroft, it is marked ”HUBER-ROETHE / VILLIGEN BAD” – for a small German Art Pottery firm Huber-Roethe, Bad Villingen, circa 1905

An English rarity, this large (34cm) simple vessel shows the aesthetic of the Arts & Crafts potters: simple functional design. It also show’s the potter’s inspiration in the Asian designs of Song Dynasty China. Inside is as beautiful as the outside, with the fingermarks of the potter making a graceful fluted pattern right down to the base.

The potter was George James Cox, of the Mortlake Pottery in South London, signed & dated 1912.

We’re currently preparing our next MOORABOOL AUCTIONS sale – date to be announced, latter October.

It features some fine Australian pieces, including a group of Australian Motorsport Grand Prix prizes.

From the FIRST Australian ‘TT’ Grand Prix, held on Phillip Island in 1928, we have the ‘Shell Cup’, a giant silver-plate affair, won by Alex Finlay on a B.S.A. bike ‘just taken out of the box’!

Shown here is the 1935 Time Trials prize, a rare original German bronze kangaroo ‘Mystery Clock’, won by Les Murphy for fastest time in his MG P-type. We also have the ‘Shell Cup’ he won the same year.

Rare Australian Artworks include a ‘View of Launceston’ watercolour by the extremely rare convict artist Frederick Strange, c. 1858, and our recently identified George Peacock oil (below), another of our convict artists, which we have titled ‘View of Sydney Harbour from Carrara House’, circa 1855.

More to come!

Welcome to our latest Fresh Stock. This one is a ‘Staffordshire Special’, with some early figures dating to the late 18th – early 19th century – as well as a good selection of classic Victorian pieces.

There’s a couple of Highwaymen, one titled ‘Dick Turpin’, the other facing horseman traditionally being his companion Gentleman-Robber, ‘Tom King’ (actually Mathew, not Tom….) .

There’s a lovely ‘primitive’ miniature group of Victoria & the love of her life, Albert. There’s cats, dogs, the Royal Children riding goats, and the exotic image of Lady Hester Stanhope riding her camel….

And there’s Mademoiselle d’Jeck, a 4-ton prima-donna…. (see more on her at the end of this post).

These subjects wouldn’t be hard to find on present day social media – and so, this Staffordshire Collection is a great illustration of the ‘Social Media’ aspect fulfilled by these charming, quirky figures from the late Georgian & Victorian eras.

This remarkable Staffordshire group tells the story of one particular elephant: ‘Mademoiselle d’Jeck’, the star of the stage in the decade after the Napoleonic Wars. Starting in England in 1806, she travelled back & forth between the Continent , England, and a tour of America before her untimely death in 1837. This figure dates to around that time, but commemorates an earlier stage appearance. In 1829, she had appeared with great success in the Paris Olympic circus, starring in the play ‘l’éléphant du Roi de Siam‘ (“The Elephant of the King of Siam”). After a short season, and a quick translation into English, the show was launched across the Channel, in the Adelphi Theatre, London, and ran from mid-1829 into early 1830.

Mademoiselle d’Jeck was a 4-ton prima-donna…. with her behaviour earning her a reputation as an absolute monster, having broken many people’s bones, and even killing a number of her keepers.

And….she’s still around! Read all about her interesting but sad story as a travelling attraction on our special blog report here >

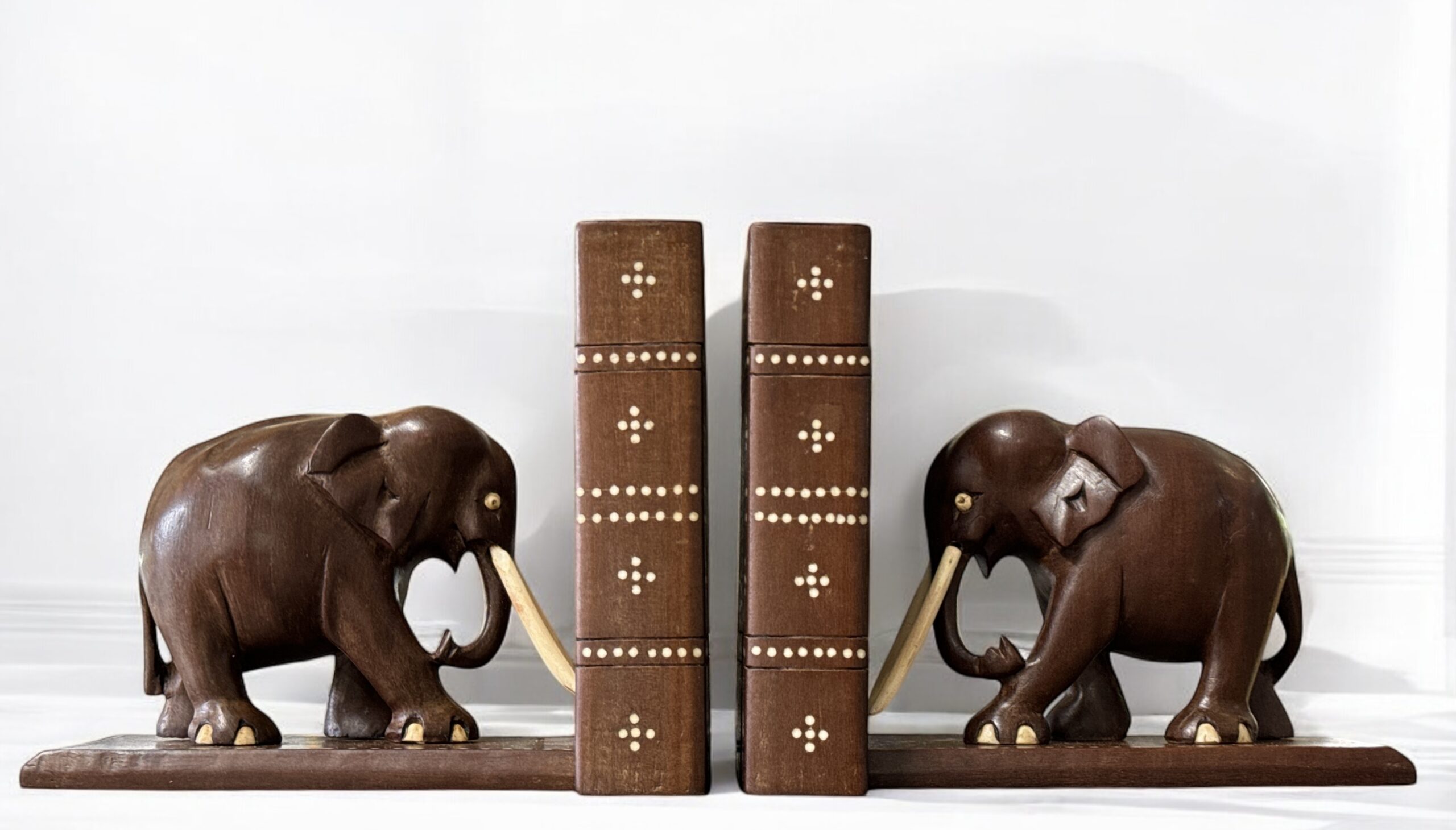

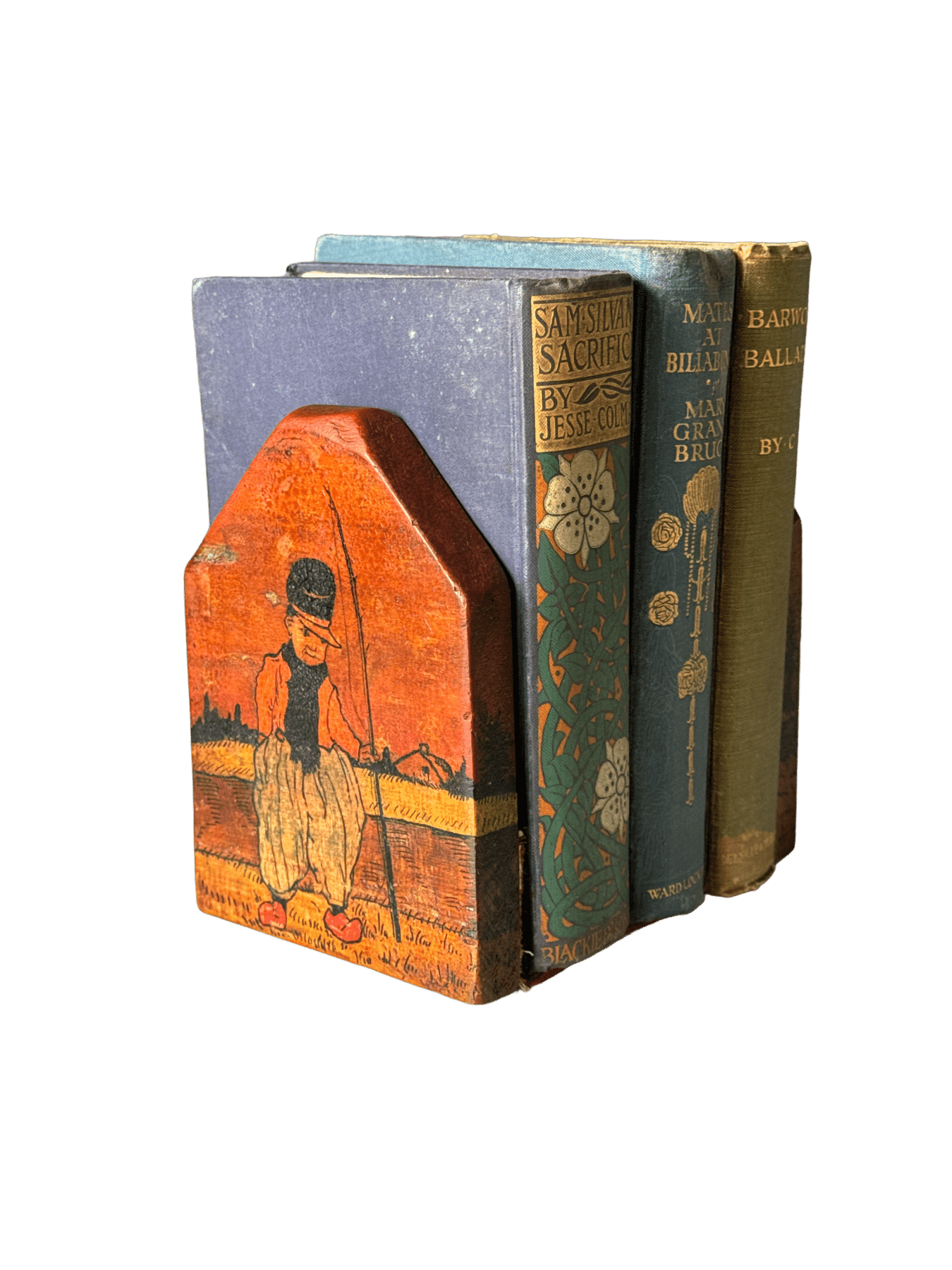

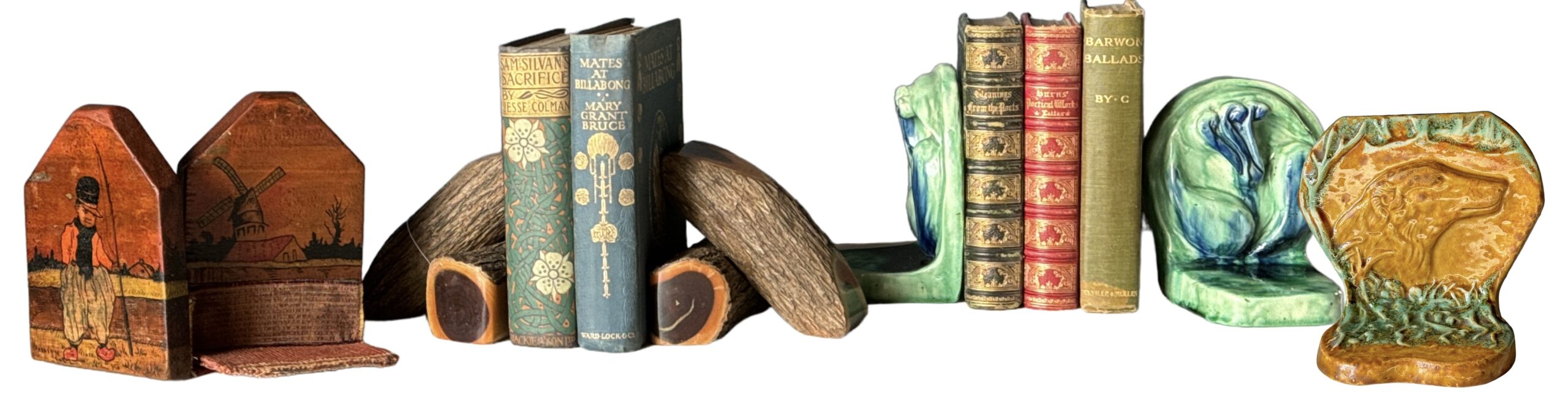

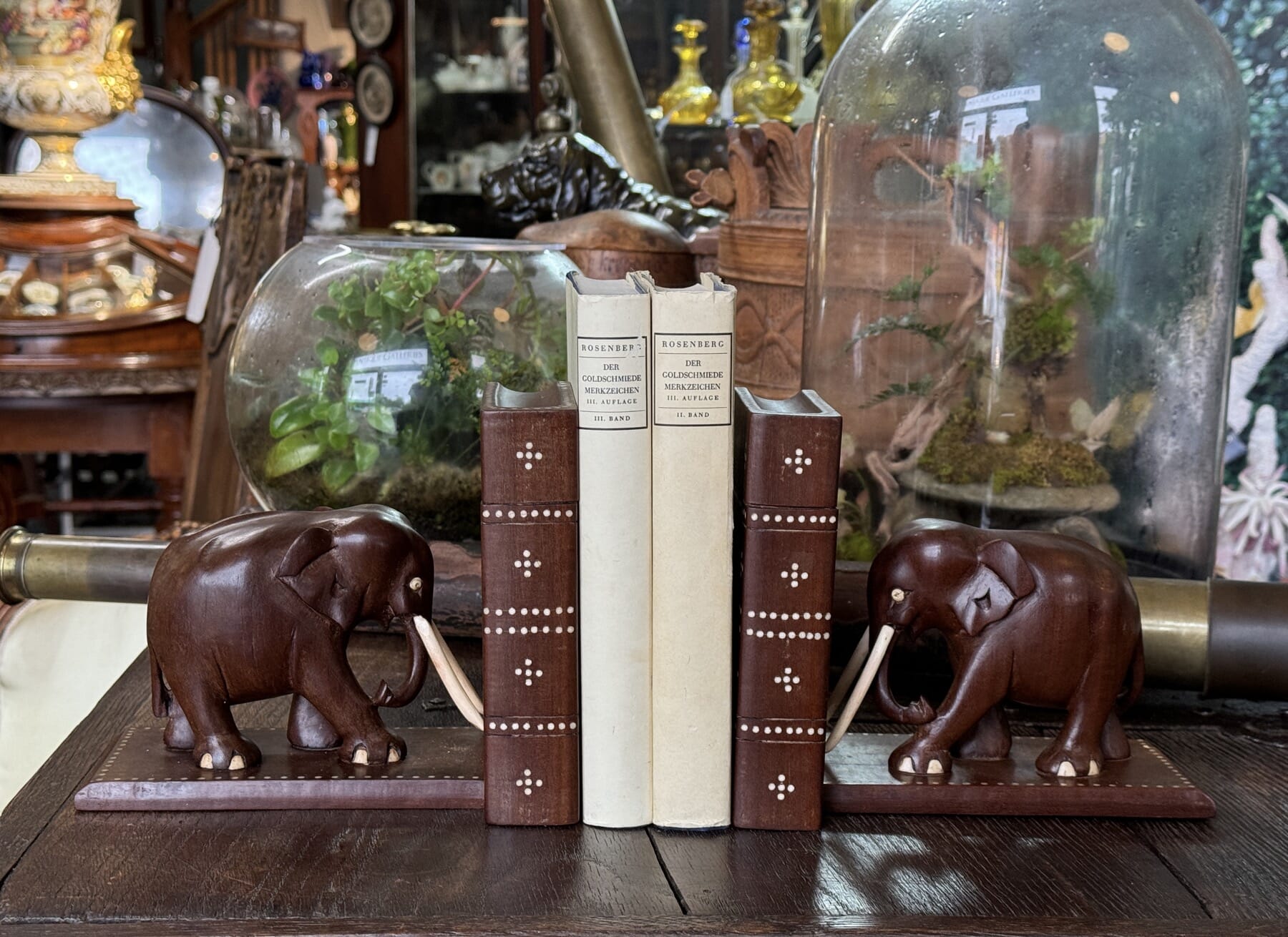

Always handy, and don’t they dress up a bookshelf?

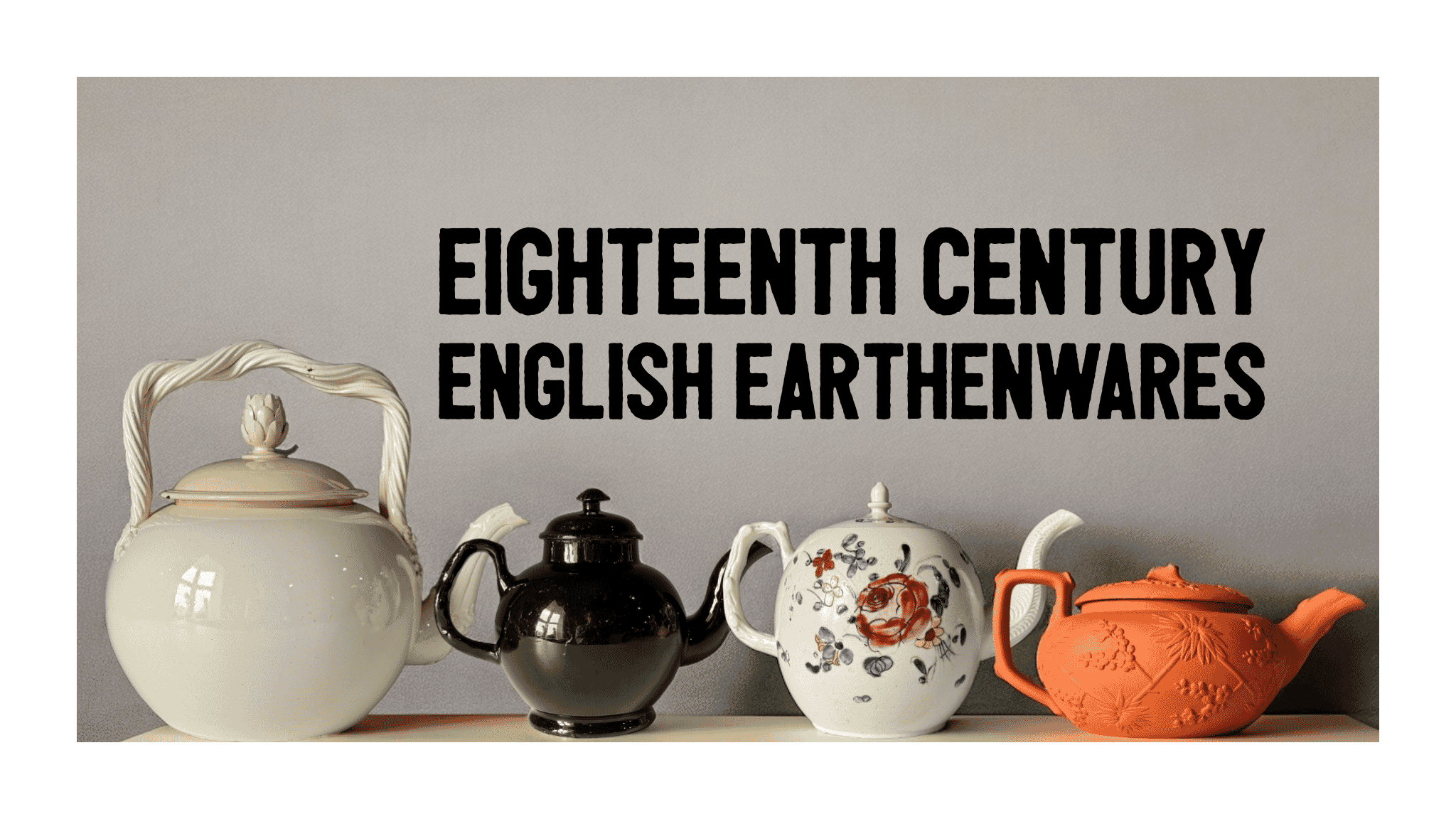

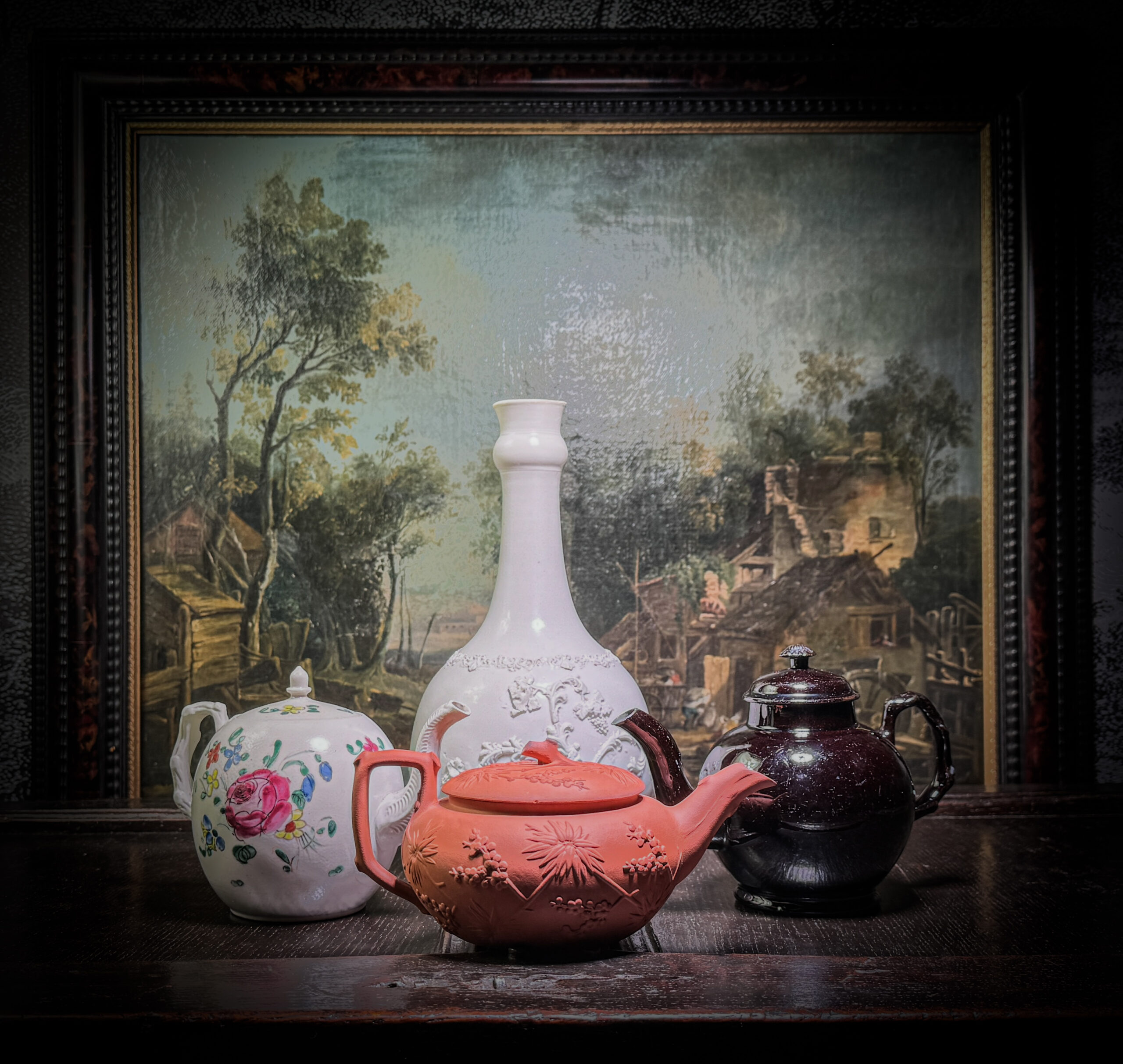

Creamware

Creamware is the term for an English earthenware body with a definite ‘cream’ tone, popular in the latter half of the 18th century and replicated across Europe. It emerged from the experimentation of Staffordshire potters seeking a local alternative to expensive Chinese porcelain around 1750. Their innovation yielded a refined cream to white earthenware with a lustrous clear lead glaze, prized for its lightweight construction and pristine finish, making it ideal for household use.

It was not expensive to produce when compared with porcelain, but also not as robust; replacements were probably a necessity if you were using Creamware tea wares or tablewares. After its heyday in the 1780’s, Creamware remained popular well into the 20th century despite competition from other ceramic types. Today, it is valued for the pleasant off-white body and refined shapes often decorated with bright spontaneous on glaze enamel flowers.

Salt glaze

Salt glaze refers to a distinctive ceramic made by the English potters in the mid-18th century, with an ivory-white stoneware body lightly glazed with a clear covering having a texture resembling orange peel.

This forms on the white high-fired stoneware body when common salt is introduced into the kiln at its highest temperature. During firing, sodium from the salt reacts with silica present in the clay, resulting in the formation of a glassy sodium-silicate coating. This glaze can exhibit a range of slight hues, usually colourless but also found in shades of brown (due to iron oxide), blue (from cobalt oxide), or purple (from manganese oxide).

The result is a glistening white product, usually slip-cast and very lightweight & thin, yet also very tough. Forgive me for making the comparison, but it could be mistaken for a plastic! The glaze is transparent, and fits tight and thin against the body, meaning any moulded decoration is as sharp and crisp as the clay beneath. It has become a highly desireable field to collect in the English Earthenwares field.

Redware

The Chinese were fond of a red clay sourced near the city of Yi Xing, on the Yangtze River Delta. When Europeans started trading with them in the 17th century, the ‘Yixing Stonewares’ were a popular item. Naturally, the local European potters were keen to provide versions of this suddenly popular ware, and the potters of Delft, in Holland produced a ‘clone’ of the Chinese – often with the same decoration – in the latter 17th century, followed by the Eeler Brothers, Dutch silversmiths who came to London in the 1680’s and produced the first English redwares. Meissen was a latecomer, with J.J.Böttger discovering a fine high-fired red ware body now named after him in 1706. By the mid 18th century, the potters of Staffordshire and elsewhere were making Redwares.

Characterized by its rich reddish-brown hues derived from iron in the clay oxidising in the firing process, English Redware exemplified both utilitarian functionality and aesthetic charm. Crafted with meticulous attention to detail, these pieces often featured simple yet elegant designs, at first copying the imported Chinese wares, but soon reflecting the prevailing tastes of the era. Commonly used for everyday household items such as teapots, jugs, and mugs, English redware found its place in both rural cottages and aristocratic homes alike. Despite its widespread popularity, redware production faced challenges from the emerging dominance of porcelain and other fine ceramics. Wedgwood brought it back to the tasteful table in the late 18th- early 19th century with a refined version they called ‘Rosso Antico’, and other firms through the Victorian era continued to make ‘redwares’ in small numbers. The original 18th-century English redware remains a testament to the skilled craftsmanship and enduring legacy of the era’s pottery traditions.

Jackfield

Jackfield is largely a generic name for a class of black/brown bodied earthenwares with a glossy ‘black’ glaze. I emphasise ‘black’ as close examination reveals it is actually made up of mostly dark brown tones, which combined with a dark-toned clay body appears black to the naked eye.

Traditionally this type of ware was said to be made at a pottery works located at Jackfield, near Coalport in Shropshire – which became the name for the type. But excavations and other evidence suggest that at the same time, such pieces were also made in Staffordshire and at other ceramic centres. The shapes and mouldings are often closely related to the other bodies detailed in this article, showing the black products were made alongside red wares , cream wares and salt glaze. Perhaps ‘black wares ‘ would be a more accurate name, but the ‘Jackfield’ name persists.

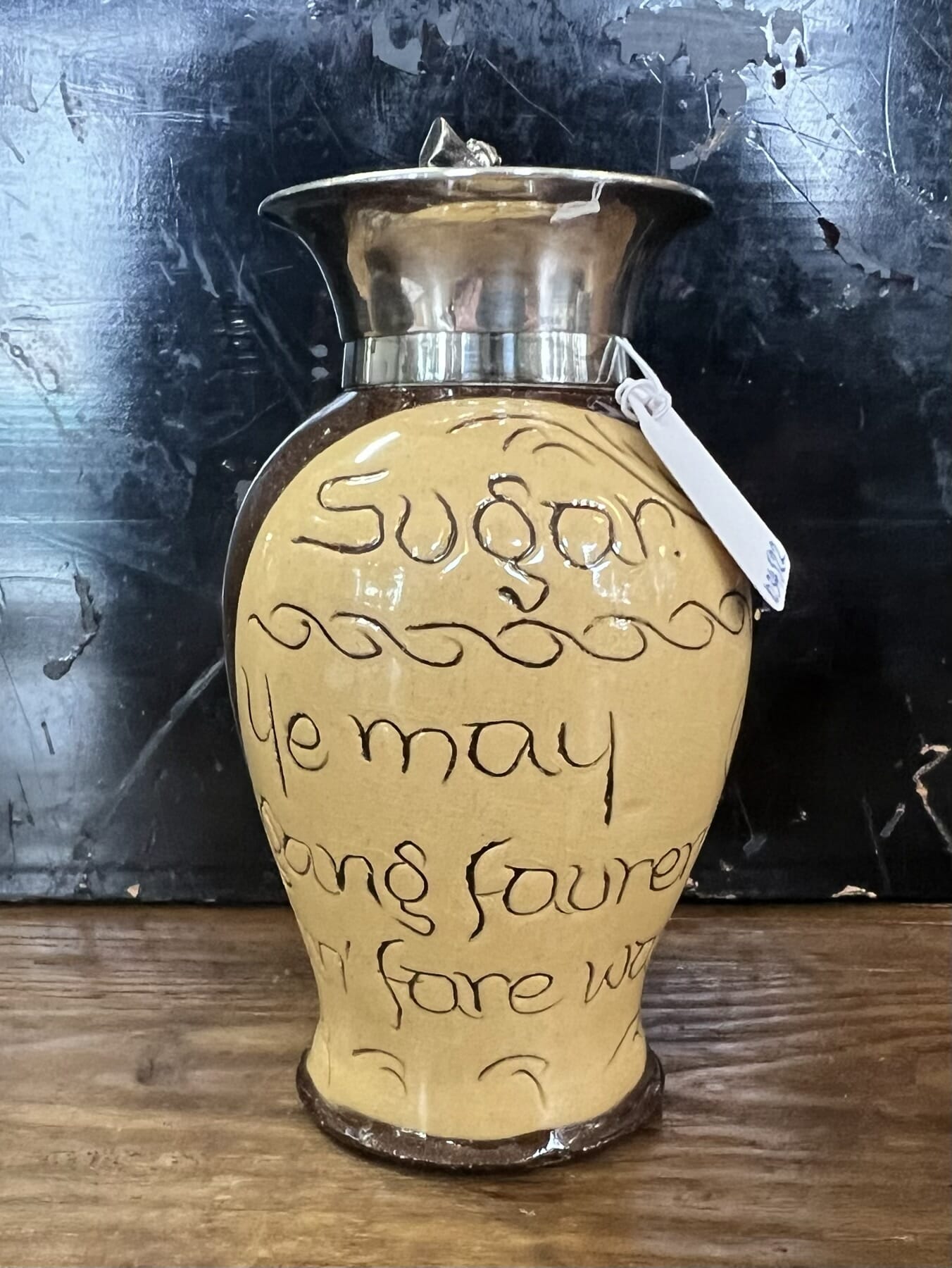

Decoration was hard, as the black surface didn’t allow for the usual decorative technique. Rare ‘cold-painted’ examples show that some were decorated in colourful oil paints, often with dedications and dates, painted onto a piece to order by a retailer, independent of the potteries.

Today, it is collected for the dramatic impact it makes in contrast to the usual white or off-white alternative wares.