The “kakejiku” is a Japanese hanging scroll; it is a work of painting or calligraphy, which is usually mounted with silk fabric edges on flexible backings.

Archives: Antiques Wiki

Description.

Keeling

Keeling is a fascinating small factory that was only positively identified in the late 1990’s. The wares are often in the Chinese Export style, of which the best known manufacturer is Newhall.

In the 1970’s was given the placeholder ‘Factory X’ name until it could be attributed to a known manufacturer. Alongside it were two other Newhall-type manufacturers, Factory ‘Y’ and ‘Z’.

Current research has revealed ‘X’ is in fact A & E Keeling, ‘Y’ is still an unknown smaller maker from circa 1790-1800, and ‘Z’ is Thomas Wolf & Co.

Anthony Keeling (1738-1815) was a Tunstall, Staffordshire, potter. He married Ann, the daughter of well-known potter Enoch Booth, and built the original Phoenix Works in Tunstall. His earlier wares are recorded as being Queensware, Black Basalt, but not porcelain. He had, however been a part of the partnership of Hollins, Warburton & Co, who had purchased the rights to make hard-paste porcelain from Champion of Bristol in 1781; however, he was once of the disgruntled members who withdrew. By 1792, when he is recorded at Hanley, Staffordshire, Porcelain manufacturing is in full swing. Records from the Wedgwood Archives reveal he was buying his raw materials from Wedgwood – the China Clay and China Stone necessary for a hard-paste porcelain mix.

Production period can be defined as beginning circa 1784, at Tunstall, and ending circa 1807 in Hanley.

The highest patten number recorded is 426, and over 300 patterns have been discovered, with around half having a pattern number associated.

There is one definitive book on the subject for further reading:

Jean Barratt “A&E Keeling – Formerly Factory X. – Shapes and Patterns on Porcelain, Gomer Press, Wales, 2009

ISBN 978-989-20-1816-4

John Joseph Mechi (1802-80) was a London businessman & innovator of the Victorian era.

John Joseph Mechi (1802-80) was a London businessman & innovator of the Victorian era. His father was Italian and was employed by the household of George III, marrying a local girl.

Beginning his career in 1818 training as a clerk, he set out on his own in 1828 as a ‘cutler’ in Leadenhall Street. He moved into his address at 4 Leadenhall Street in 1830.

Products included his ‘magic shaving strap’, which made him a small fortune early on (until beards became fashionable!) , and items made of Papier-mâché.

He was a prolific inventor, coming up with all sorts of interesting concepts he patented. He had a thriving farming business later on, and published a series of accounts on ‘Profitable Farming’. He was an Alderman of the City of London, but unfortunately became involved in a failed financial scheme, and was declared bankrupt -right when he was destined to become the Mayor of London….

Neville W. Cayley

Neville William Cayley is known as ‘Junior’ to differentiate him from his father, notable ornithologist and painter-of-birds, Neville Henry Cayley.

Cayley Junior was born in 1886, and went on to study art before receiving the commission to illustrate the first of many books.

Perhaps the best known is ‘What Bird Is That?’, first published 1931, becoming an all-time best seller in Australia and still in print today.

His love of birds was unescapable, following in his father’s footsteps; he was a council-member of the Royal Zoological Society of New South Wales (president 1932-33), the Royal Australasian Ornithologists’ Union (president 1936-37), the Gould League of Bird Lovers and the Wild Life Preservation Society of Australia, and was a trustee of the National Park in 1937-48. He also held several exhibitions of his paintings: in 1932 one was presented to King George V.

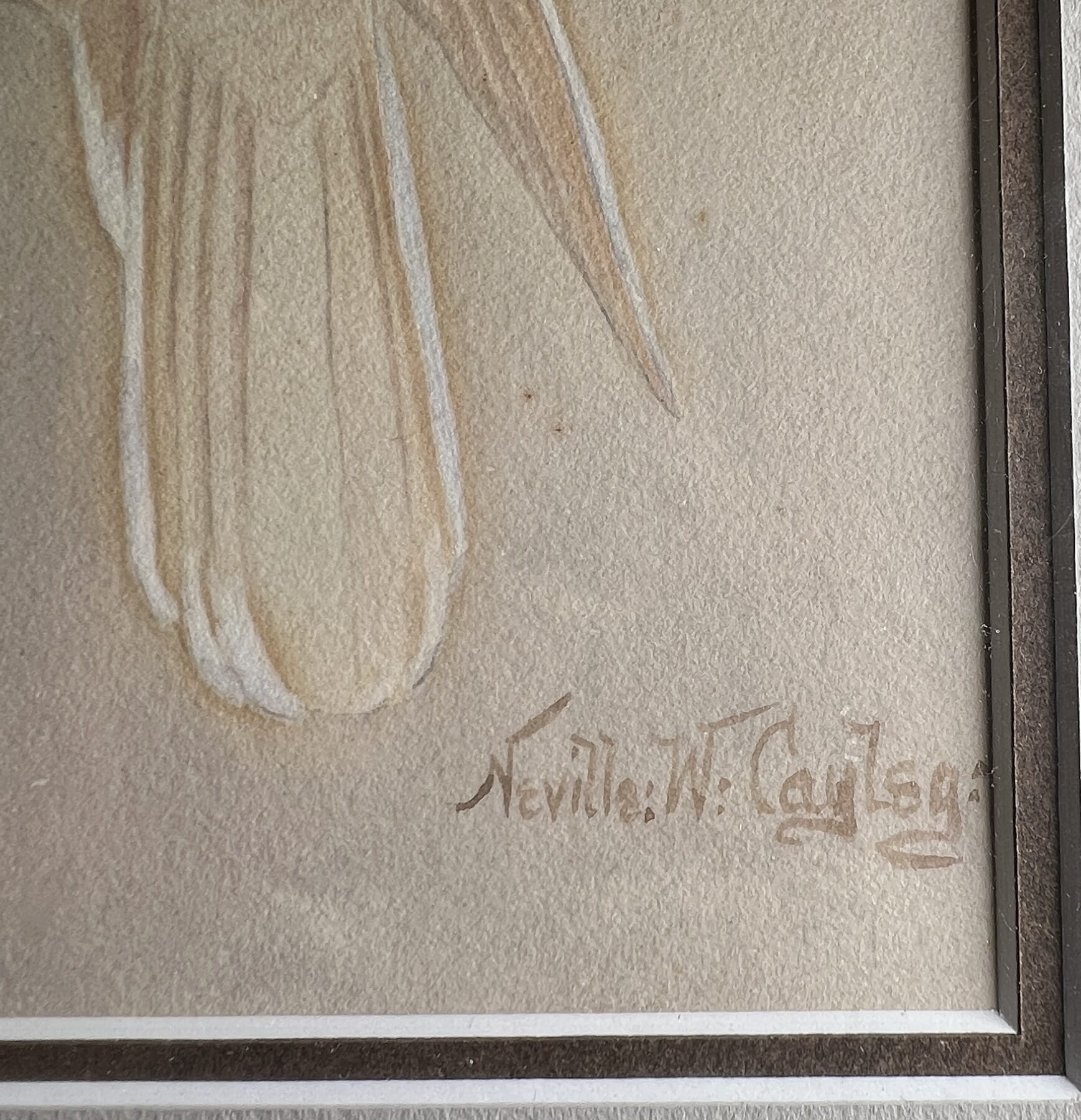

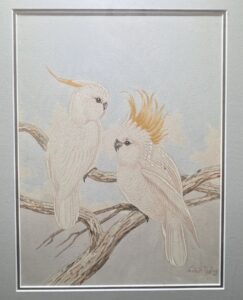

Above is a work in the stock of Moorabool Antiques, Geelong. It is interesting to compare this work with the later datable N.W. Cayley’s. His early style is described as ‘pretty’, his later as very accurate to life. In this example, there is a lot less detail, and a more naive charm. It is quite different to the life-like illustrations used in ‘What Bird is That?’.

The work has some of the earlier style seen in his father’s works, Neville Henry Cayley. We suggest this work is an earlier W. Cayley work, before the defining of his mature ‘accurate’ style.

Growing up in the shadow of his father, regarded as the best of the bird artists in Australia, must have been inspirational, and his obvious artistic ability must have made his father proud; perhaps this is a work of the young Neville Cayley when he was indeed ‘Junior’, before going to art school.

Pardoe

Thomas Pardoe 1770-1823

Thomas Pardoe (1770-1823) was a major artist in the porcelain trade of the late 18th/early 19th century period. Born in Derby in 1770, he was apprenticed to the Derby porcelain works around 1785 where he undoubtedly learnt his skills as a china painter. After probably some time at Worcester, he was at the Cambrian Pottery in Swansea, Wales, by 1795. Here he became the chief decorator of the fine white earthenware they produced. In 1809 he established an independent decorating studio in Bristol, which continued for the next decade. In 1820, he was employed at Nantgarw, Wales, at the behest of William Weston Young. Young had been financing the Nantgarw factory, and when it failed, Pardoe was able to cut the loss to some degree by decorating the stockpile of white porcelain ready for sale. He continued at this task until his death in 1823.

Pardoe’s style shows his origins, with a classic ‘English Flower’ style commonly seen at Derby. While at Derby, he would have crossed paths, perhaps worked under William Billingsley – regarded as the supreme ‘English Flower Painter’ of the period. They had been born in the same parish in Derby, with Billingsley being 12 years older. A sketch book in the Victoria & Albert Museum, compiled by a descendent of Pardoe, includes examples of Billingsley’s work dating to the time Pardoe was still in Derby, clear evidence of the master’s influence. However, Pardoe’s flowers definitely have their own style, with the best way to describe them being ‘fluid’. His technique looks like the paint is still drying – often lacking clarity & detail, and missing the subtle graduation of tone seen in Billingsley’s work.

He was very versatile, with every type of decoration being evident, from Chinoiserie to landscapes, sheashells to birds, and of course the ever popular flower groups.

His botanical studies are different, being careful renderings of specimens often sourced in the Curtis publications. They are detailed and much more precise, although once again, detail and tone seen in the watercolour originals can be lacking. The main method of identifying these botanical subjects as being by Pardoe is by his distinct handwriting – the practice beng to copy the common name from the Curtis print to the back of the plate, usually in a red script.

Qajar

The Qajar Dynasty, or the ‘Persian’ Empire , controlled parts the area of present day countries Iraq, Iran, and Afghanistan, as well as the southern parts of Georgia.

The Qajars ruled from 1779 to 1924, coming from Astarabad, south-east of the Caspian Sea. Under the Qajars the capital of Persia was moved to Tehran.

They were very highly educated, and proud of the past history of their lands. As a result, their artforms incorporate historical details of a number of earlier cultures, such as the Mesopotamian civilizations. As an islamic nation, they were Shia, which allowed the portrayal of the human image.

Their technology followed the ancient methods in ceramics, such as Iznik pottery – but were also eager to embrace the western technological advances such as railroads. A university opened in Tehran in 1851.

The major powers of the 19th century – Britain, America, and Russia – all manipulated the rulers and the region, and a series of disruptive interventions and revolutions caused the destruction of the dynasty in 1924.

Qalamzani

Qalamzani is the Iranian metal-craft method of embossing, then incising, designs into base metals. This can be copper, silver, tin or nickel. The surface is often different, for example a silvered surface with copper beneath; or a blackened surface with silver beneath. When the craftsman uses a sharp tool to inscribe through the upper metal, the colour of the metal beneath is revealed in contrast.

The technique has been in use for over 1,000 years in the region, and is still popular today.

Two distinct styles can be found, the Tabriz and Isfahan styles. Tabriz uses more chiseled bright-cut designs and depends on wrist-action, while Isfahan utilised a hammer and more embossing.

Radloff Collection

The Radloff Collection was a remarkably varied Australian collection, put together in the mid 20th century by Leslie Edwin Radloff (1898-1967), of Adelaide. After his death, the collection was transported to Sydney and sold through Lawsons in 1967, in a 6-day auction. It covered the whole spectrum of desirable 18th & 19th century Ceramics, Glass, enamels, and other small interesting items.

We regularly find interesting items with the collection/ sale labels.

Simon Harris

Simon Harris is an interesting under-documented silversmith of the Georgian era.

He is on record in the London essay records with his mark ‘HS’ registered in 1795.

He’s recorded in Grimwade (p538,751) as having paid indenture duty for an apprentice, Joseph Emden, on September 15th, 1796 (‘Simon Harris of Saint Mary Whitechapel, working silversmith’).

There are numerous pieces attributed to him with this mark, including teapots, made during the first two decades of the 19th century. He seems to have left London by 1810, but pieces continue to be assessed there. Between 1811-15, he is on record at the Exeter Assay office, and his address at this time was the Plymouth Docks, just down the coast. His wares were therefore either assessed at Exeter, a short boat trip up the coast, or London, a slightly longer trip but a destination with an enormous market for his products.

This spoon is a superb example of this rarely seen silversmith, and pre-dates the official registration of his mark in 1794.

Sprigging

Sprigged – a method used to add a small moulded decoration to a pottery vessel while it is still soft.

A negative mould is filled with clay, which can be removed and carefully applied to a surface with a little moisture to soften the join. Once fired, it becomes a part of the vessel.

Usually applied to wheel-made items of simple form.

Not to be confused with Moulded, which is an integral part of the decoration of a moulded vessel.