‘Alabaster’ has always been the term used by us Antique dealers to describe any translucent, whitish stone…. but have we been mis-labeling it? Sometimes, different industries have different terms for the same thing; I remember arguing with a floor-tile salesman, who insisted that with tiles, ‘ceramic’ was not the same as ‘porcelain’, something I still cannot get my head around, as porcelain is surely a variety of ceramic!

It seems we have the same issue with ‘Alabaster’.

The term is used by geologists to describe just one type of mineral – Gypsum. This is a soft material, ie you can scratch it with your fingernail – great for quickly carving. You may well be surrounded by it right now, as it is the main ingredient in plasterboard walls!

Antique dealers (and archaeologists) are a little more liberal in our allocation of the definition – we include Calcite in ‘Alabaster’. This is a much harder material – sometimes called ‘Onyx-marble’, a further confusion as Onyx is a completely different mineral!

Generally, if it is a fine whitish opaque stone – that lets the light through – we call it ‘Alabaster’.

Both of these ‘Alabasters’ (Calcite and Gypsum) have the same basis: the element Calcium, which has often come from the shells of dead marine organisms. You’ll also find it forming where ground-water pools – or where it drips in caves, forming stalagmites / stalactites.

And of course, add a little pressure & heat, and you have Marble. This much tougher Calcium-based rock is the most familiar to us, being the most luxurious building material available since ancient times.

This brings us to today’s story; the Indian ‘Alabasters’. These are whitish carved stone items from India.

The Taj Mahal is perhaps the most fabulous example of the Indian stonework – although the craftsmen who worked on it were brought in from all over Asia, and it owes a lot to the Persian – Moghal influence – but with a good infusion of Indian Hindu elements. The petra-dura panels of decoration is particularly stunning, with semiprecious stones sourced from as far as China (Crystal) Tibet (Turquoise) and Afghanistan (Lapis).

It was constructed to be ‘the most beautiful tomb in the world’ for the wife of the Moghal emperor Shah Jahan, and he was himself buried there on his death in 1666. A modern estimate for the cost at the time would translate to $1.2 billion Australian Dollars!

By the 19th century, it was in a state of disrepair – and during the British occupation and the subsequent 1857 rebellion, panels of inlaid work were prised out by British soldiers…

In the late 19th century, British viceroy Lord Curzon embarked on a restoration project of the monument, and it rapidly became a tourist attraction on its completion in 1908. Nearby towns who hosted the visitors discovered a demand for ‘souvenirs’ – and the British restoration effort had no doubt attracted a good core of cunning craftsmen, who were able to create lovely small souvenirs for the visitors.

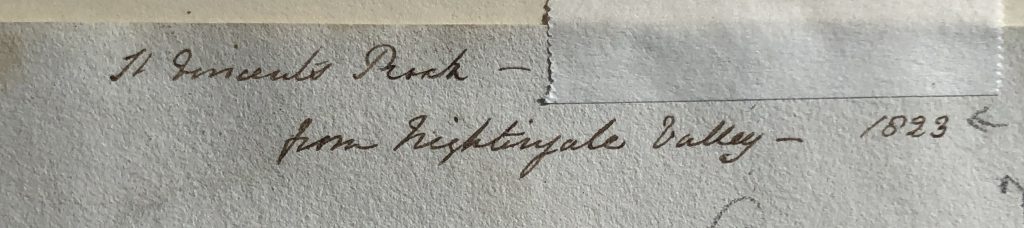

They’re hard to date accurately, as they were probably made for a long period of time – so a piece with a date is always helpful. This example has one such inscription to the back:

But are they Alabaster? We have to say no, not in the official definition of the word; they are the same material as the Taj Mahal, and therefore a fine white marble which is translucent when cut thin…. and because of that, they are lovely objects worthy of the semiprecious stone title ‘Alabaster’!

So they are almost alabaster, but have been left to cook a little longer!

See the Indian Marbles here >>

See all the Alabasters in stock here >>