Welcome to our latest Fresh Stock release at Moorabool.

This week we have a fine selection of English Porcelain figures, and a collection of English Enamel patch & snuff boxes.

Enamel patch boxes and snuff boxes were everyday items for fashionable 18th century people of social status.

Patchboxes, as their name suggests, were used to store ‘patches’ – literally small wax-based cosmetic ‘boils’ that were seen as essential beauty products in the 17th & 18th centuries. This ‘beauty spot’ fashion had a practical origin; the diseases of the era would often leave facial scars, and a patch could be used to fill the mark; however, it obviously became something more, with perfectly healthy un-diseased beauties feeling they had to add artificial patches to their faces!

The patchbox, with its compact size and elegant appearance, provided a convenient and stylish way to carry these essential fashion accessories on one’s person, ready to apply if needed. You can tell them by the mirror seen inside the lid – something seen into the modern era with the ‘powder-compact’.

Snuff boxes were used to store ‘snuff’ – essentially powdered tobacco, a popular stimulant in the 17th and 18th centuries. Snuff-taking was not only a social ritual but also a symbol of refinement and status. These boxes, often passed down as heirlooms, were prized possessions that reflected the taste and sophistication of their owners, making them cherished artifacts right to the present day.

Fresh to Stock – 18th century Enamel Boxes

-

English enamel patch box, flowers & insects on seeded ground, steel mirror c.1780$580.00 AUD

English enamel patch box, flowers & insects on seeded ground, steel mirror c.1780$580.00 AUD -

Birmingham Enamel snuff box, hand painted couples & landscapes, c. 1775$780.00 AUD

Birmingham Enamel snuff box, hand painted couples & landscapes, c. 1775$780.00 AUD -

Birmingham enamel box, hand-painted scene with couple, c. 1765$790.00 AUD

Birmingham enamel box, hand-painted scene with couple, c. 1765$790.00 AUD -

English enamel snuff box, hand painted Watteauesque scene, c. 1780Sold

English enamel snuff box, hand painted Watteauesque scene, c. 1780Sold -

Birmingham enamel snuff box, gent & flower-girl, c. 1765$780.00 AUD

Birmingham enamel snuff box, gent & flower-girl, c. 1765$780.00 AUD -

Samson of Paris enamel box, after an English 18th century type, c. 1860$545.00 AUD

Samson of Paris enamel box, after an English 18th century type, c. 1860$545.00 AUD -

English enamel patch box ‘A Trifle from BRIGHTON’ c. 1800Sold

English enamel patch box ‘A Trifle from BRIGHTON’ c. 1800Sold -

English enamel patch box, A TOKEN OF LOVE c.1800Sold

English enamel patch box, A TOKEN OF LOVE c.1800Sold -

Birmingham enamel patch box, Venetian scene, c. 1760$580.00 AUD

Birmingham enamel patch box, Venetian scene, c. 1760$580.00 AUD -

English enamel patch box, flowers, Birmingham c. 1780Sold

English enamel patch box, flowers, Birmingham c. 1780Sold -

English enamel patch box, ruins with ‘From a Friend’, c. 1790$380.00 AUD

English enamel patch box, ruins with ‘From a Friend’, c. 1790$380.00 AUD -

English enamel patch box, rose bud, c .1790Sold

English enamel patch box, rose bud, c .1790Sold -

English enamel box, green gingham + ‘gold’ flowers, C.1770$880.00 AUD

English enamel box, green gingham + ‘gold’ flowers, C.1770$880.00 AUD

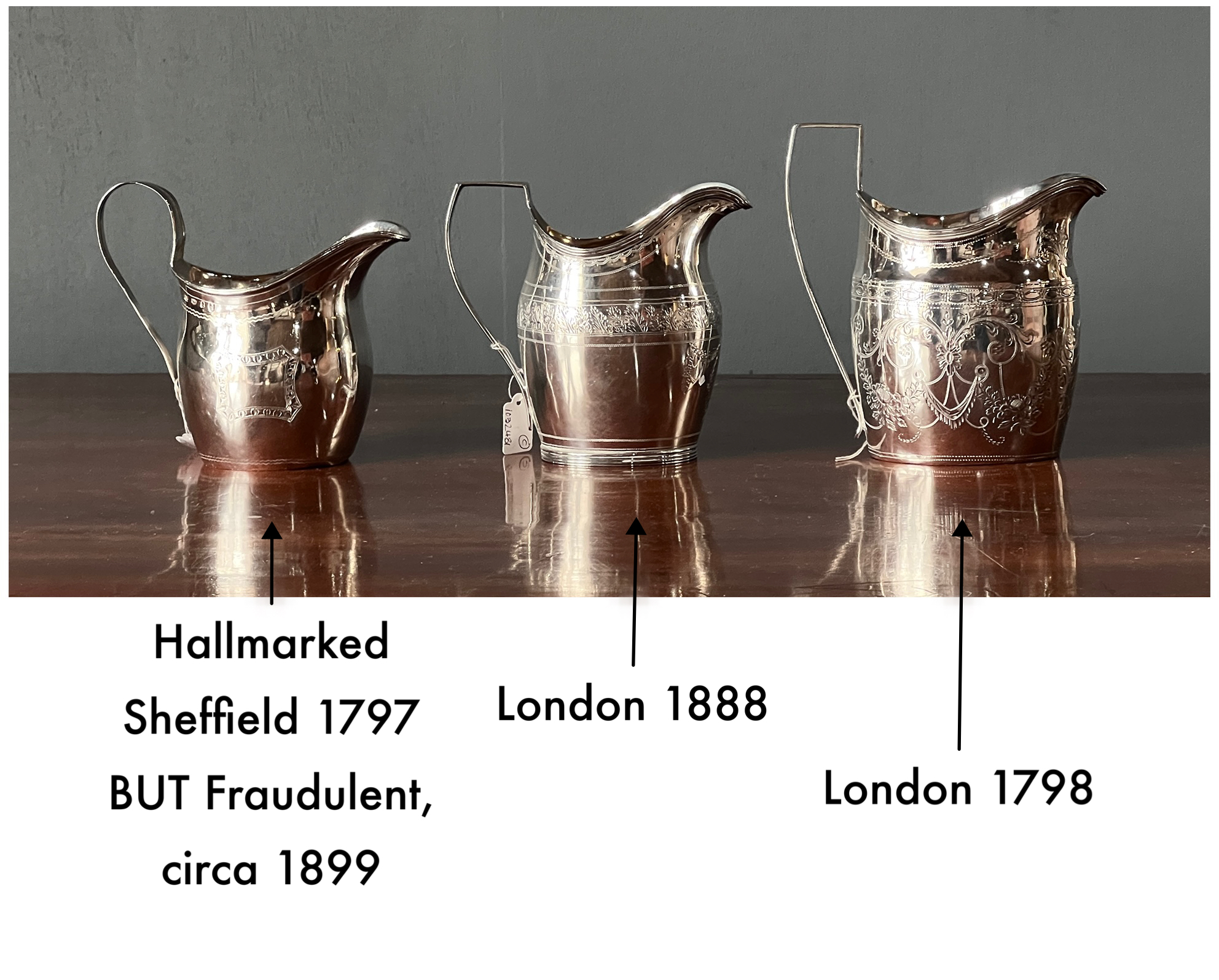

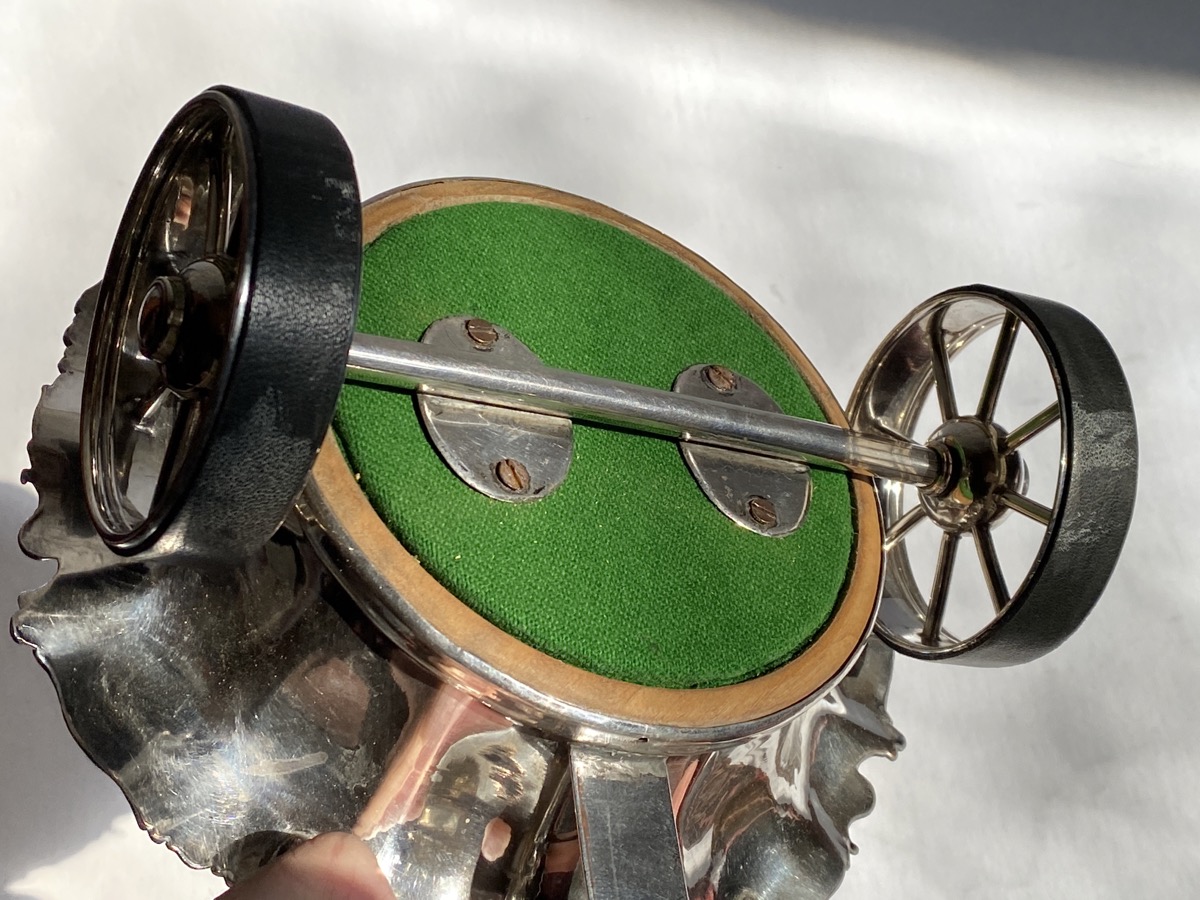

SPOT THE FAKE

One of these lovely enamel boxes isn’t what it seems: can you tell which?

Derby Figures

Derby figures, originating from the renowned Derby Porcelain Factory founded by William Duesbury in 1756, represent a pinnacle of 18th-century ceramic artistry. These exquisite porcelain sculptures, often depicting scenes of pastoral life, classical mythology, or notable historical figures, are celebrated for their impeccable craftsmanship and artistic detail. From elegant ladies and gentlemen in period attire to elaborate animal and mythological motifs, Derby figures encompass a diverse range of subjects and styles, each meticulously sculpted and hand-painted with vibrant enamels. Reflecting the tastes of the aristocracy and burgeoning middle-class of Georgian England, these figures adorned the mantelpieces and tables of affluent households, serving as both decorative ornaments and symbols of status and refinement. Today, Derby figures remain highly sought-after by Collectors and Connoisseurs of Fine Things, cherished for their timeless beauty.

Fresh to Stock – Derby Figures – and more!

-

Derby figure of a boy, standing holding a basket of flowers c. 1785$295.00 AUD

Derby figure of a boy, standing holding a basket of flowers c. 1785$295.00 AUD -

Derby figure of a boy, standing holding a basket of flowers C 1785$295.00 AUD

Derby figure of a boy, standing holding a basket of flowers C 1785$295.00 AUD -

Derby figure of a boy, standing holding a basket of flowers c.1785$295.00 AUD

Derby figure of a boy, standing holding a basket of flowers c.1785$295.00 AUD -

Derby figure of a boy, standing holding a basket of flowers circa 1785$295.00 AUD

Derby figure of a boy, standing holding a basket of flowers circa 1785$295.00 AUD -

Derby figure of a lady Gardener, fine quality, c. 1775Sold

Derby figure of a lady Gardener, fine quality, c. 1775Sold -

Large Derby figure group, newly identified as ‘Prudence and Discretion’ no. c. 1775$2,750.00 AUD

Large Derby figure group, newly identified as ‘Prudence and Discretion’ no. c. 1775$2,750.00 AUD -

Gold Anchor Chelsea figure of ‘Spring’, circa 1765$850.00 AUD

Gold Anchor Chelsea figure of ‘Spring’, circa 1765$850.00 AUD -

Bow figure of a musician, with Flageolet and Tabor, c.1760Sold

Bow figure of a musician, with Flageolet and Tabor, c.1760Sold -

Rare Derby figure, ‘Gentleman playing pipes’, c, 1765Sold

Rare Derby figure, ‘Gentleman playing pipes’, c, 1765Sold -

Pair of Derby figures of children -‘Boy eating apple, Girl eating curds-and-whey’ c.1785$895.00 AUD

Pair of Derby figures of children -‘Boy eating apple, Girl eating curds-and-whey’ c.1785$895.00 AUD -

Derby figure of ‘Summer’, from ‘The Infant Seasons’ c. 1765$1,250.00 AUD

Derby figure of ‘Summer’, from ‘The Infant Seasons’ c. 1765$1,250.00 AUD -

Meissen child representing ‘Autumn’, late 18th centurySold

Meissen child representing ‘Autumn’, late 18th centurySold -

Pair of Derby figures, ‘Ranelagh Dancers’ c. 1765Sold

Pair of Derby figures, ‘Ranelagh Dancers’ c. 1765Sold