We are always fascinated by the origins of things…. when and where did it all begin?

In the porcelain world, it was of course China, around 1,000 years ago. This was so foreign and magical to the Europeans that pieces which made the perilous journey across the globe were only affordable by the most wealthy, being far more valuable than gold.

This all changed as the lure of such riches led to experimentation, and the first instance of a European porcelain body appears in the Medici courts in the 16th century, bankrolled by Francesco I; today, only 70 pieces have been identified, and the enterprise was a dead-end.

The next successful production appears in France. In Rouen, a pottery industry had for many years been producing Faience – earthenware pieces with a white tin-glaze, as an imitation of a white porcelain body. They developed a distinct design, known as a ‘Lambrequin’ – a border with repetitive symmetrical floral elements, borrowed from Baroque designs often seen in embroideries, metalworks, and related artistic products. In 1673, a privilege to make porcelain was granted to Louis Poterat, and he seems to have experimented without a viable production of commercial scale resulting – only a possible dozen Rouen porcelain pieces have ever been identified. A 1702 comment in the petition from the next factory mentioned described the Rouen effort at porcelain manufacturing as this:

“…..(they) did nothing more than approach the secret, and never brought it to the perfection these petitioners have acquired”.

-1703 Saint Cloud Royal Petition

The designs are ‘le style de Berain’, taken from the 17th century designs of Berain, who was influenced by earlier Baroque designs which had borrowed heavily from Roman wall paintings!

This example in the Rosenberg Collection, Geelong, is probably Moustiers (Clerissy workshop), but is typical of the type made at Rouen during the period discussed.

The first commercially successful porcelain manufacturer is the factory at Saint Cloud.

This manufactury, like Rouen, began as a faience producer. A 1664 ‘Royal Privilege’ was given to a Parisian merchant named Claude Révérend, ‘..to produce faience and to imitate porcelain in the manner of the Indies (China) ‘ As a merchant, he was importing faience from Holland, and would have been very familiar with the superior Chinese porcelains.

He selected a manufacturing base, and in 1666 set out to make faience products – in the manner of Rouen – on the outskirts of Paris, at Saint-Cloud. Within a few months, Claude Révérend had passed ownership to his brother, Francois Révérend. He had actually lived for many years in Rouen, and it is no surprise that these first products of Saint Cloud faience are very close to Rouen products.

An artist employed at this time to paint the tin-glazed faience wares named Pierre Chicaneau is the important character in the development of the first commercial porcelain production in Europe. He is possibly from Rouen, and George Savage speculated in his 1960 “Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century French Porcelain” that he may have been exposed to the porcelain experiments while there.

He begins at Saint Cloud in the 1660’s, and in 1674 he was made the firm’s director. He died in 1677, and it is the documents provided by his widow’s petition to the King for a Royal Privilege to make porcelain that gives us the full story of what was happening in Saint Cloud through the late 1660’s and early 1670’s; active pursuit of the secret of making porcelain.

His widow wrote in the 1700 petition

“Pierre Chicaneau, having applied himself for many years to the making of faience and having arrived at a very high level of perfection in this work, wanted to push his knowledge still further and find the secret of making true porcelain; for this purpose he undertook several experiments with different materials and tried different finishing techniques, which resulted in works that were almost as perfect as the porcelain of China and the Indes”

-1700 Saint Cloud Royal petition by the Chicaneau family

They go on to state the first success – a repeatable, commercial prospect that allowed manufacturing of the product – was achieved by the firm around 1693.

Dr Martin Lister, physician to Queen Anne in England and prolific writer, visited the works in 1698, writing;

“I saw the potterie of St Clou with which I was marvellously well pleased, for I confess I could not distinguish betwixt the pots made there and the finest China ware I ever saw. It will, I know, be easily granted me that the painting may be better designed and finished because our men are far better masters of that art than the Chineses; but the glazing came not the least behind theirs, not for whiteness, nor the smoothness for running without bubbles. Again, the inward substance and matter of the pots was, to me, the very same, hard and firm as marble, and the self same grain on this side vitrification. Farther, the transparency of the pots the very same.”

Examples of Saint Cloud in Moorabool’s current stock – click for more

Moorabool is pleased to offer a piece of this earliest commercial production from what can be seen as the first European Porcelain Manufacturer*.

Our piece was a necessity on the elegant tables of the time, where salt was an important – and expensive – commodity that enhanced the dining experience. It was also a status symbol, as while the Crown imposed a tax on salt (la gabelle), exemption was made for the privileged Nobles and Clergy.

Saint Cloud Salt circa 1700

Several of these open salts would have been scattered down the table amongst diners. There are metal examples of the same form, and clearly the porcelain copies them.

The decoration is classic Saint-Cloud, with a repeating pattern of lambrequin motifs in underglaze blue. Such decoration appears on the full range of Saint-Cloud shapes, such as cups & saucers, cosmetic jars, and even eggcups. Comparing the patterns on ours with other examples is fascinating, as it appears the artist was not faithful to any specific design – there are endless slight variations regarding the location of the various leaves, flowerheads, and the symmetrical tendrils that define them.

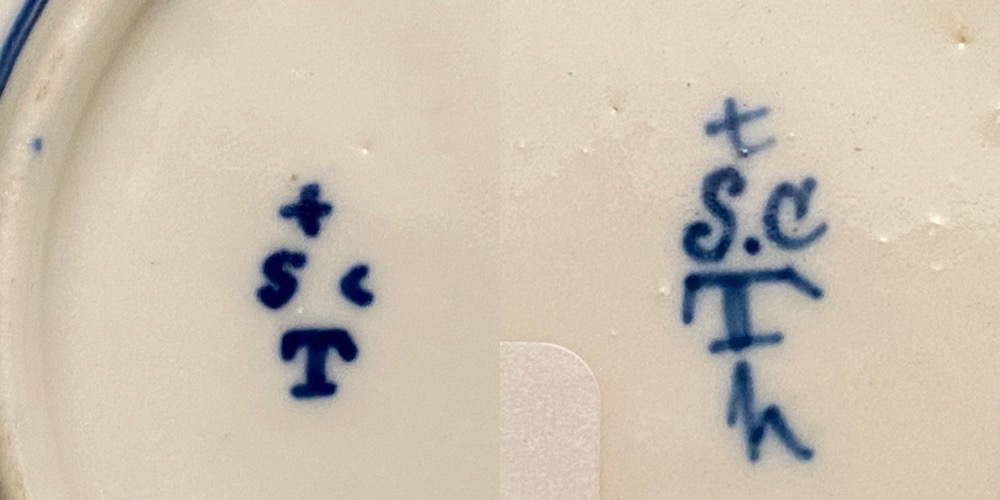

[metaslider id="80388"]The ‘Sun’ mark is the earliest Saint-Cloud mark, and refers to the most important patron in France – Louis XIV, the ‘Sun King’. The factory location at Saint-Cloud was chosen because of the King’s younger brother, Duc d’Orleans, had an estate there, and became a patron of the fledgling factory. Louis XIV died in 1715, and the mark would most probably not have been used after that date; the more usual ‘St C’ begins during the second decade of the 18th century, and is identifiable as being post- 1722 by the addition of a ‘T’ beneath, indicating the change of Director to Henri Trou in that year. They continued making similar porcelain wares throughout the 1730’s-40’s, and finally closed in 1766.

The second example (Rosenberg Collection, Geelong) has an extra ‘h’, a painter’s mark.

Other examples can be seen various museum collections around the globe;

the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris has 5 examples, of which 2 have the ‘Sun’ mark and are dated 1697-1700, while the other three are unmarked and catalogued “Saint Cloud or Paris”, post-1700 (reflecting the other porcelain manufactories in Paris who copied Saint Cloud in the early 18th century). In 1997, the collection catalogue (Christine Lahaussois) suggests a date of 1697-1700. In 1999, the catalogue for a NY exhibition (“Discovering the Secrets of Soft-Paste Porcelain at The Saint-Cloud Manufactory”, editor Bertrand Rondot) illustrates three of the same examples as definite Saint-Cloud, and dates them all post-1700, with the closest to our example (including a Sun mark) being 1700-1715.

An example with the same ‘Sun’ mark, similar decoration, can be seen in the British Museum, dated 1700-1710

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/H_Franks-330

An example in the Victoria & Albert, London, is very similar, with the ‘Sun’ mark, dated conservatively 1693-1724.

http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O307789/salt-cellar-saint-cloud-porcelain/

(It even has a chip to the rim – although unlike our example, un-restored!)

Sources & Further Reading:

George Savage “Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century French Porcelain” 1960

Bertrand Rondot (editor) “Discovering the Secrets of Soft-Paste Porcelain at The Saint-Cloud Manufactory” 1999

Aileen Dawson “French Porcelain -a catalogue of the British Museum Collection” 1994

Christine Lahaussois “Porcelaines de Saint-Cloud, La collection du Musee des Arts Décoratifs” 1997

*I should note; when I use the term ‘Porcelain’ in this article, it is best described as ‘Artificial Porcelain’, meaning it was not the same as the Chinese products, as it lacked one of the main ‘stiffening’ ingredients. This is commonly called ‘Soft-Paste’, and defined the earliest French and English products.

True Porcelain, in the Chinese manner, was produced by the Chinese from around the Song Dynasty (900 AD), and in Europe, the experiments at Dresden (and subsequent production at Meissen) were by chance identical in their basic ingredients, and this product is known as ‘Hard Paste’.

There is also a ‘Soft-Paste’ twist, with some fascinating experimental products appearing in England in the latter 17th century, possibly pre-dating the French efforts. John Dwight of Fulham was awarded a patent for porcelain in 1671, and may well have been successful – but not commercially!