‘China’ was for centuries an expensive, exotic import from the far East. There were many attempts at producing it in Europe, but it wasn’t until 1709 that the alchemist Johann Friedrich Böttger apparently ‘discovered’ the secret, and in 1709 he was responsible for the founding of the Meissen porcelain factory, under the direction – and funded by – Augustus II ‘The Strong’. This was the first porcelain factory to make commercial amounts of porcelain in Europe, according to the authentic Chinese definition of ‘porcelain’ – and remarkably, it is still a functioning concern, being a state run business in Dresden in the modern age.

The secret to making porcelain was kept for the next two decades, helped by the location of the factory, in the Albrechtsburg castle in Meissen, which is located on top of a hill with a single gatehouse for access. Workmen’s comings & goings were strictly controlled, and none knew the entire process to the mystery of porcelain production. However, the value of the product meant there were many other attempts in Europe to emulate Meissen’s success, and industrial espionage resulted in workmen being lured away from the works. This was instigated by a private businessman in Vienna, a Dutchman named Du Paquier, and he gives his name to the second porcelain works to be founded in Europe. He made his first limited examples in 1719, and for the next 25 years was the only real rival to Meissen for porcelain in Europe.

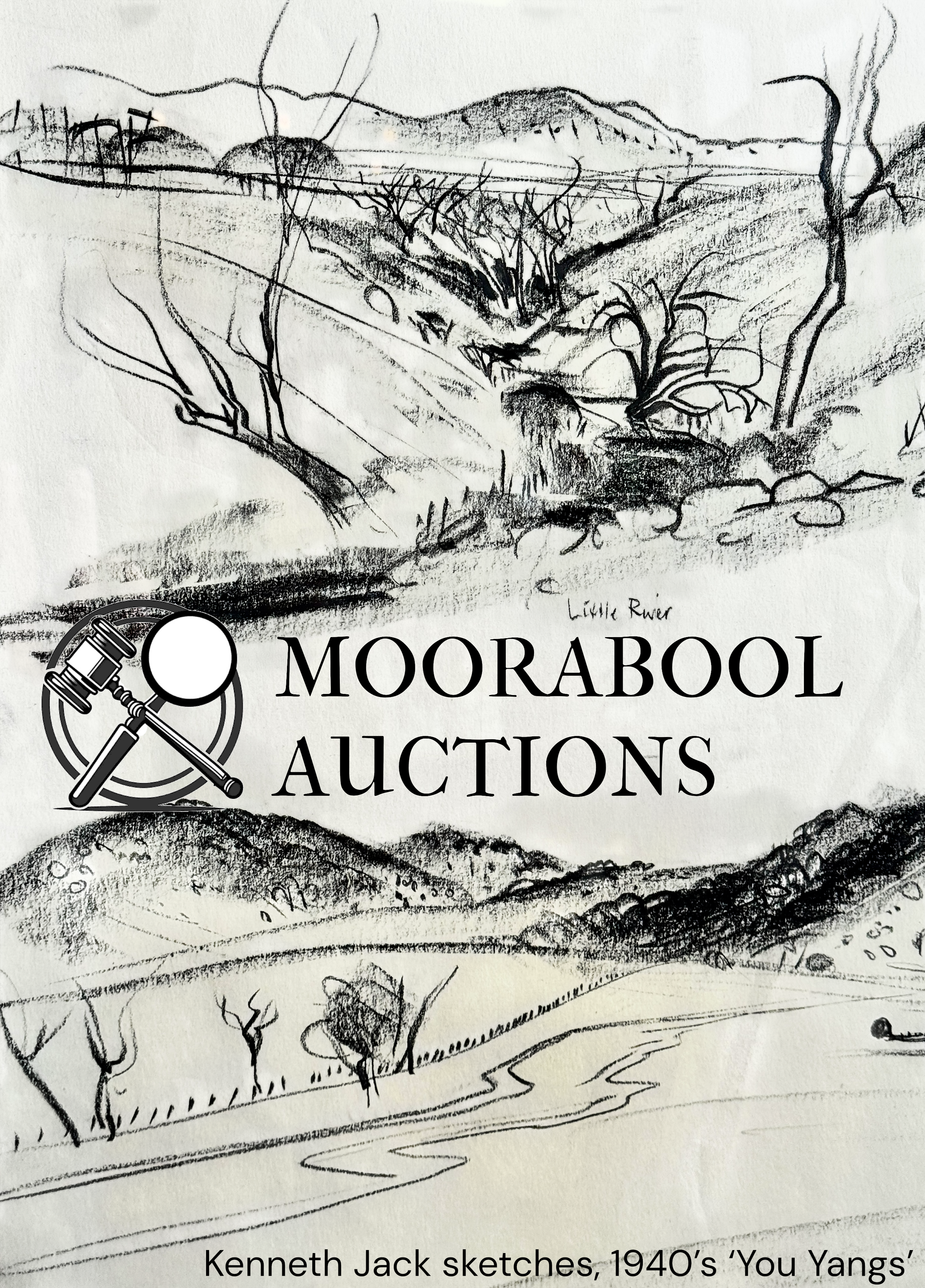

Moorabool is excited to be able to offer an example of porcelain from the infancy of each of these factories, the 1st and the 2nd to exist in Europe. On the left is a Meissen cup, of the early porcelain body known as ‘Böttger Porcelain’, dating to c. 1715. On the right is a Du Paquier cage cup/stand, circa 1725.

Both of these amazing rarities will be a part of our 2015 Catalogue, opening in Geelong & online on March 28th.

They will be the subject of their own page here in the near future, with more photos & in-depth history.

perhaps was not used much due to the issues we see on this cup & saucer: the blue tends to bead into clumps, and the thick yellow enamels shift in the heat of the enamel firings. While the yellow pigment had been a very early Sévres development, the tone seen here appears in the early 1780’s and is not repeated after the Revolution. There are a handful of specimens scattered around the globe in various collections, making this a most rare & desirable item.

perhaps was not used much due to the issues we see on this cup & saucer: the blue tends to bead into clumps, and the thick yellow enamels shift in the heat of the enamel firings. While the yellow pigment had been a very early Sévres development, the tone seen here appears in the early 1780’s and is not repeated after the Revolution. There are a handful of specimens scattered around the globe in various collections, making this a most rare & desirable item.