The wonders of the Middle-East have always appealed to the Western world. It has always been ‘exotic’ and associated with luxury due to the nature of the regular contact through trade. Persian rugs were the go-to for any Victorian household, and other textiles were in great demand – and expensive.

We have recently found some metalwork & ceramics that followed this route, all the way to Australia. Mostly from one Western District (Victoria) estate, they have been in Australia for generations – quite possibly since new. Australians have always been great travellers, and collectors. The nature of the passage to Australia through the Suez Canal meant constant contact with the Middle-East, and with the number of troops who pivited through there in both Wars, it is no wonder we find Australia a great place for discovering quality Arabic wares.

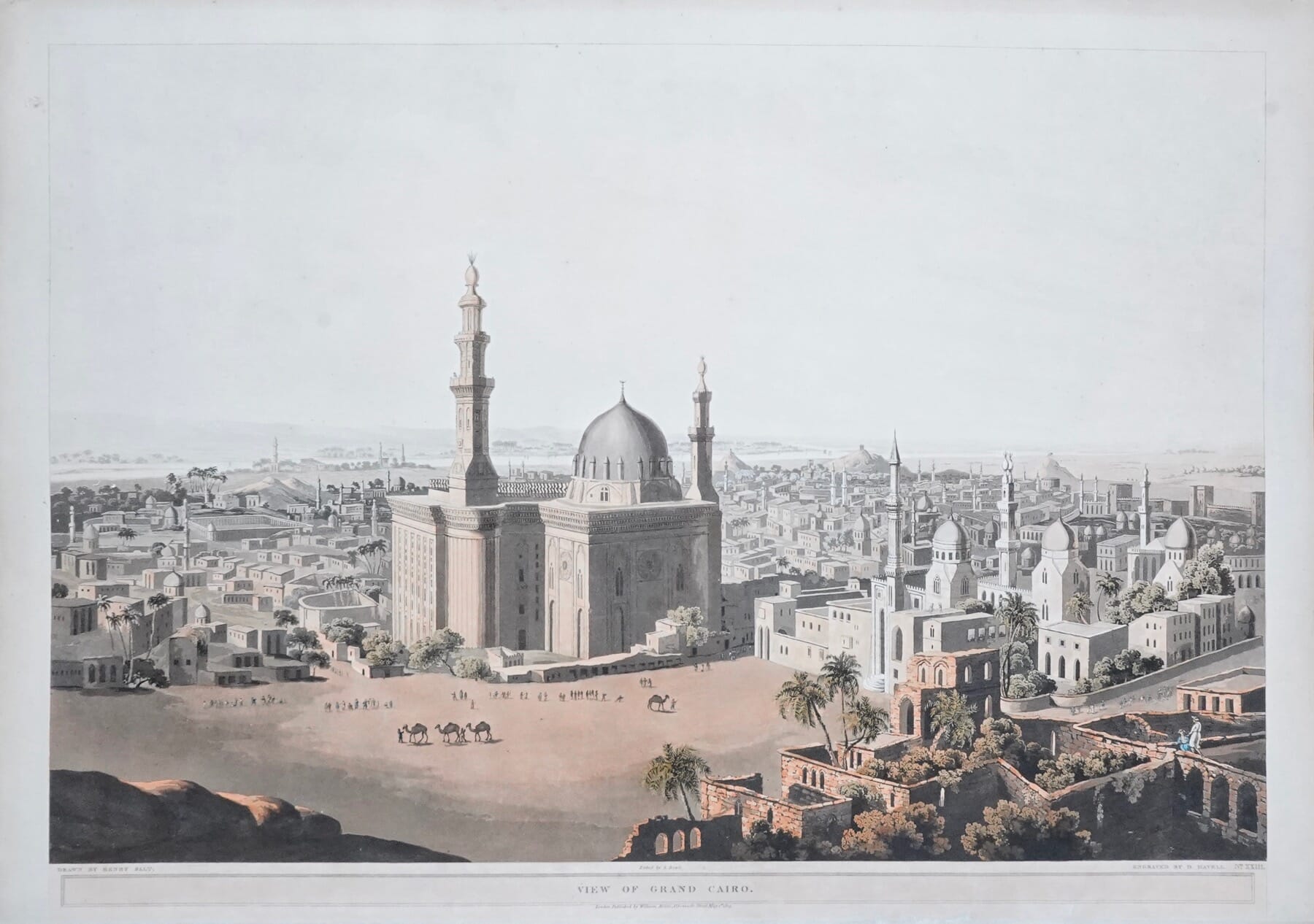

Views in Egypt, by Salt, 1809

These large-scale hand-coloured aquatints were an attempt by Henry Salt to express the scale of wonder to be seen in Egypt. Ruled by the Ottoman Empire until the French and then the English invaded, Egypt was not often visited in the 18th and early 19th century. However, once the British had the upper hand on the French, they made certain their influence was felt in the region. Henry Salt was trained as an artist, a student of Farrington and also Hoppner, R.A. – but came to love Egypt during his travels from 1802-1806, as secretary and draughtsman with George Annesley, Viscount Valentia. They embarked on a major tour of ‘The East’, visiting India, Ceylon, Abysinnia and Egypt. Salt’s drawing skills were utilised, being used as the basis for illustrations in his employer’s publication, ‘Voyages and Travels’.

They were part of a large folio, “Twenty-four views taken in St Helena, the Cape, India, Ceylon, the Red Sea, Abyssinia & Egypt”, published 1809. These were the only two to depict Egypt.

Salt went on to become British Consul-General in Egypt in 1815, where excavated extensively, procuring a large number of antiquities for The British Museum and for his own collection. He sent a large collection of antiquities to The British Museum in 1818. Many other pieces were sold to private collectors, the most notable of these being the sarcophagus of Sety I purchased by Sir John Soane and still to be seen in his house museum in London today.

The engine-turning is particularly interesting and is evidence of European technology in the Egyptian workshops during the 19th century. The concentric lathe needed for engraving these lines was a European invention of the latter 18th century.

The shape is common in Europe from the 18th century, particularly in Eastern Europe, and the flower knop is copied directly from a European piece of the 19th century. The intended market would have been the Eastern Europeans, although luxury European wares were also valued by the Ottoman Court, so it could have been for use in a great Ottoman household somewhere in the eastern Mediterranean.

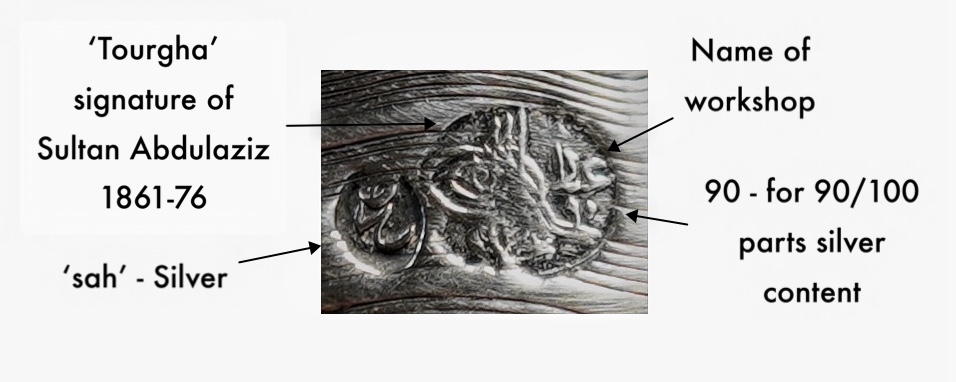

A remarkable Egyptian silver coffee pot, after an Eastern European original, Ottoman period of Sultan Abdulaziz (1861-76)

Ottoman silver of this quality is rarely seen. It would have been a very expensive luxury good, available for the Ottoman wealthy, or imported as an exotic import into Europe. Sultan Abdulaziz was the 32nd Sultan of the Ottoman Empire, and the first to travel through Europe. He was entertained by monarchs in the major European countries, with Queen Victoria entertaining him on her royal yacht in 1867 and making him a Knight of the Garter. He loved Europe’s technological progress, and was present at the ‘Exposition Universal’ in Paris in 1867. The Technology and Science from around the globe which he witnessed there led him to seek to bring the Ottoman Empire into the modern world. He was responsible for many rapid advances such as a postal service, the first railroads, and a navy that became the 3rd largest in the world after England & France. The European nature of this pot reflect this interest in the European world just next door.

The marks are found on each component, ie. body, lid & flower knop. The ‘tourgha’ is the Islamic calligraphic signature of the Sultan, with each Sultan having his own. The form of this one places it in Egypt. Next to this is the sah mark, in this case stating ’90’ as the 90% assay of silver content. The mark of the maker is found engraved on the base, within two zig-zag lines. These lines were the result of the assayer taking a sample to test the silver content, and act as further proof of the .900 grade of the silver.

Ottoman Turkish Coffee Set, .800 Silver, Circa 1900

A superb quality Turkish silver coffee set including the traditional ‘cezve‘ open-topped dingle-handled coffeepot with incredible Kufic script engraved around each piece.

Early Islamic Bronze basin

Seljuk Bronze Basin, 13th century

with a Moghul brass ewer, 18th century

This large basin was a symbol of status. Paired with a water-ewer, it was part of the ritual of hospitality to offer water to wash hands & feet – no doubt dusty from travel. What is remarkable is the size; it would have been brightly buffed originally, or plated in a shiny tin- and an impressive introduction to a visitor to a household.

On the walls are panels of Kufic script, which when translated often wish the best blessings to the guests and household. Interestingly, there are a series of brass rings inlaid around the central flowerhead motif, an early instance of the complex inlaying of metals that developed in the following centuries.

Damascus Wares

These ‘mixed-metal’ items are collectively known as ‘Damascus Ware’ due to the Souq (markets) of Damascus being full of pieces for sale. However, it is a common form of craft from around the Ottoman Empire and beyond, going back to the Seljuk Empire of the 10th century.

The Seljuk were nomadic Turkic tribesmen, who overran the region in the 10th century, taking the great city of Baghdad in 1055, and under whose rule the ‘Golden Age’ of Islamic Art was achieved.

In the 19th century, interest in the earlier Seljuk period led to a renewal of the technique and elaborate designs. In Damascus and Cairo, the Souqs encountered by westerners were full of exquisite ‘Seljuk Revival’ pieces like the vase pictured to the right.

Early Islamic Inlay, Seljuk 13th century

This rare Islamic bronze dish is decorated with inscriptions, with 6 panels of script to the rim and 4 to the interior. Another 6 can be found along the outside wall, all in very stylized ‘kufic’ type script, which can still be translated by scholars today; usually it is a blessing for the food and the consumer, often sourced from the Koran.

It is of a distinct angular form, and has been made by a combination of casting the body, then hammering & incising decoration. The body is very thick, and the result is surprisingly heavy.

It has some sections of copper inlaid as decoration, with the flower centers having rounded inserts and the structure of the central star with central copper strip. It also has silver, which has corroded; this was used for a series of crescent moons in the roundels, with a budding plant cupped by the crescent. It is tempting to see this as an early incidence of the Islamic Crescent symbol. However, while the Seljuk were Muslim, it wasn’t until the 15th century and the Ottoman Empire that a ‘crescent’ became the symbol for Islam.The other roundels have full flowers, and in combination with the new moon crescent, they are probably symbolic of ‘the cycle of life’. The quality of the bronze alloy is excellent, and this piece has survived in extremely fine condition.

Seljuk Khorasan, 13th century AD

Examples can be traced to Egypt, the Balkans, Turkey, Iran/Iraq, and of course Syria. With the rise of Islam, it became the perfect way to have both something incredibly precious & decorative, while showing correct piety; the calligraphic script is usually a quote from the Koran, often wishing health & prosperity. This script is an art form in itself, and when examining a piece, one can only admire the skill. Each metal – sometimes a bronze base with copper, silver and gold inlaid – is carefully hammered into a ‘trench’ prepared with a chisel, being careful to make the base of this incision broader than the surface cut. This results in the metal being hammered in being firmly fixed without any further work. It is then carefully smoothed & polished, sometimes engraved, leaving it proud of the surface. The entwined foliage knotwork designs are simply mesmerizing.

Most quality pieces we see are from the 19th-early 20th century, and they all look back to the earlier ‘Mamluk’ period – hence the term ‘Mamluk Revival’.

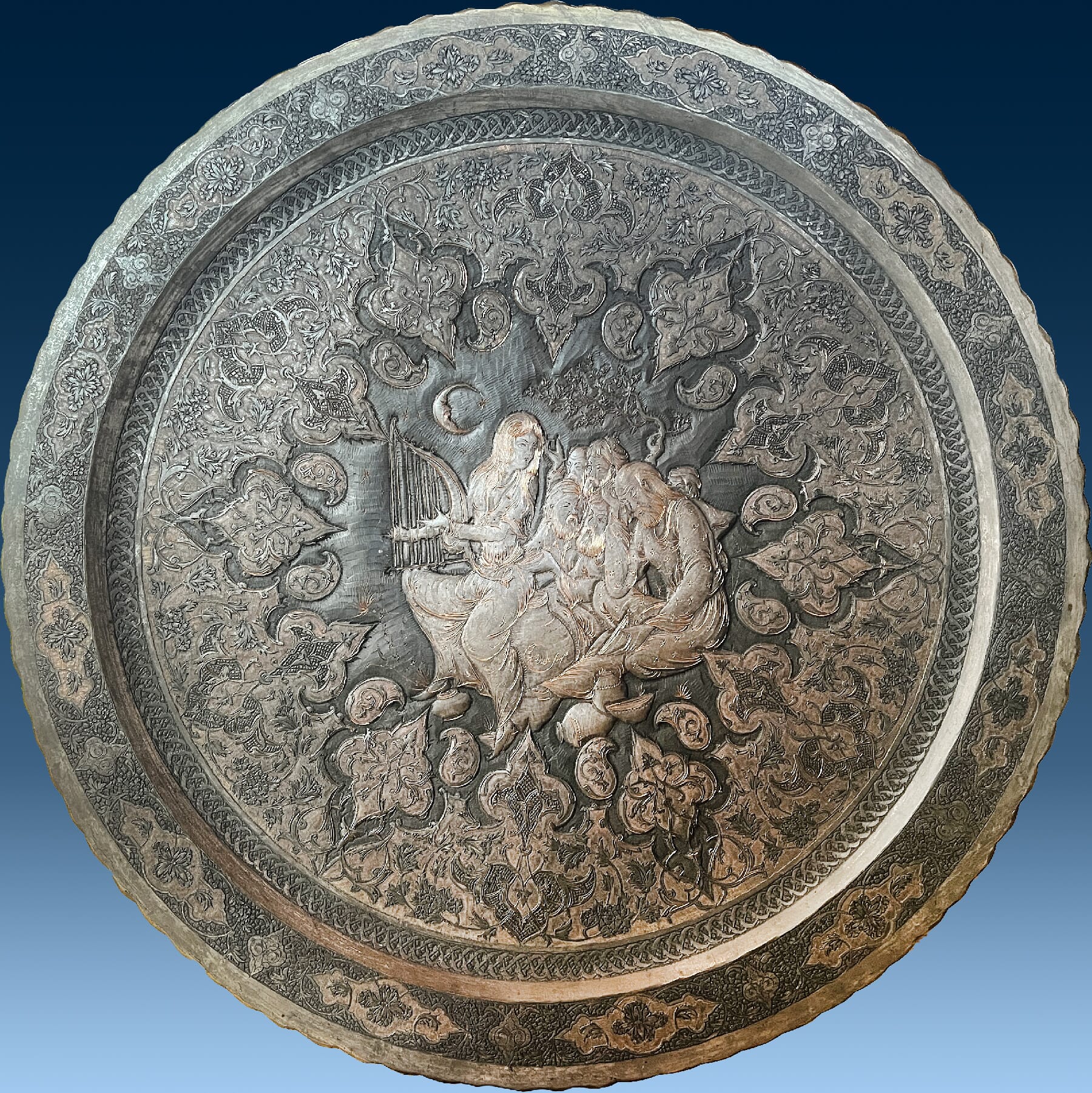

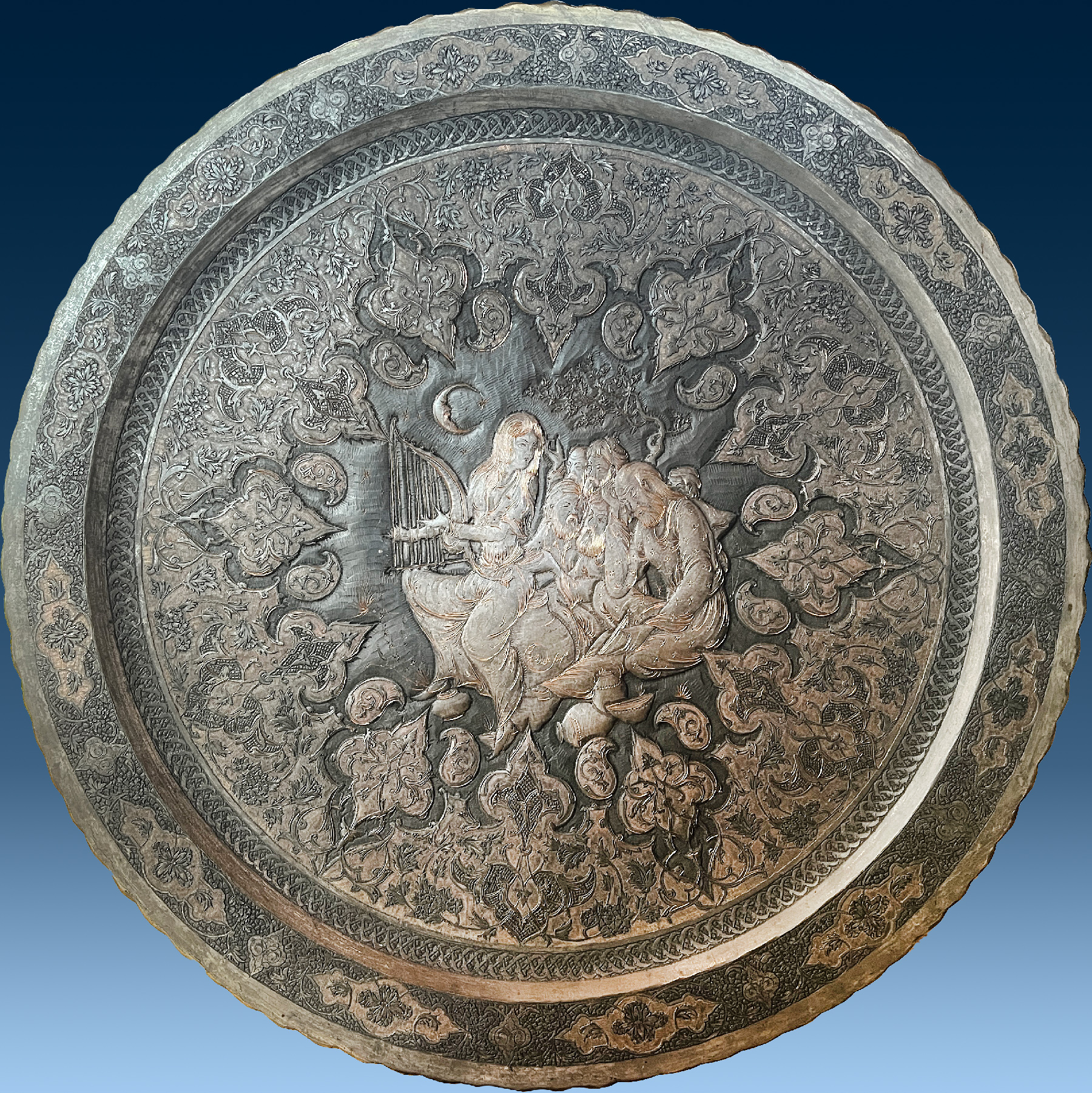

Qalamzani metalwork of Iran

The technique of ‘Qalamzani’ was skillfully developed in Qajar Persia (Iran), and continued into the subsequent Pahlavis period. It involves using a series of sharp chisels to gouge through a surface layer of metal, often revealing a prepared second metal beneath.

We have a stunning example of Qalamzani work, a very large charger. This piece has is a masterpiece, and signed by Master Mahdi Alamdari. Born in 1957, he was in his early 20’s when this piece was created. We can date it through one simple fact: it has human images. There is a story being illustrated, probably from one of the multitude of legends Persia is so rich in. As outlined below, such an image would have been prohibited by the Sharia law of the post-1979 Islamic Republic, allowing us to date this piece to the late 1970’s.

If anyone knows their Persian stories, I’d love to know the tale this scene tells – drop us a message!

It is unfortunate that Iran has become severed from the Western World since then, and interesting to examine the path that led it there. Read more by clicking the ‘Road to Isolation’ below.

A brief history of Iran’s 20th century road to isolation.

During WWII, Britain used the ‘Persian Corridor’ to access their ally Russia, and to deny Germany access to the oil fields of the region. The Russian did not leave despite the Tehran Conference, where along with the USA, they agreed to leave Iran’s borders where they had been before the war.

This led to one of the first confrontations between the USA and USSR which we remember as the ‘Cold War’: the USA then covertly performed their first ‘regime change’ by spearheading a coup to overthrow the only democratic government Iran has ever known, and installing an absolute monarch of their own choice.

This Shah, Pahlavi, came to depend on the support of the USA to stay in power – which he managed to do for the next 26 years. The USA was of course thinking strategically; Iran had access to vast oil reserves, and was adjacent to the USSR, so a strategic ally in the ‘Cold War’ they were fighting. The 1960’s-70’s were a prosperous time for Iran, with plenty of USA & UK interaction, and a time when Iranian Arts & culture were readily available to the West. This was the date our large charger would have come out of Iran.

This all changed in 1979; a festering unrest at the Western nation’s abuses over the past century – in particular, dissatisfaction at the Shah’s dependence on the USA – led to the ‘White Revolution’.

The result was a Theocracy, the Islamic Republic of Iran – following the leadership of the Supreme Leader, Khomein. As a part of the strict Sharia (Islamic Law) ideology, images of humans & animals – ie. any living thing – were ‘strongly discouraged’. This stemmed from interpretations of the displeasure of Muhammad on seeing idols in his time. The traditional arts of the Persian world came to a screeching halt, with the vast majority of artists leaving Iran for Western exile in the following decade.

The last 40 years have been isolating for Iran, as it has had the constant embargo on almost everything, and the heavy attention of the USA leaning on it. As a result, it is still a place of mystery, and the art & artifacts we come across have that same ancient sparkle of a far-away mysterious & exotic land, filled with wonderful treasures…

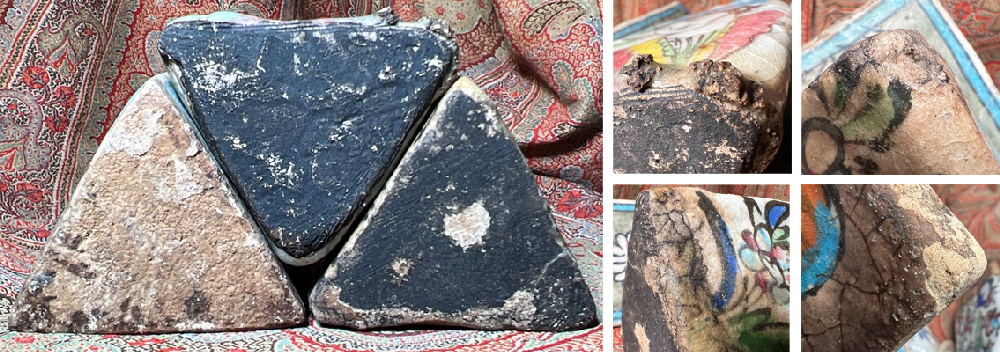

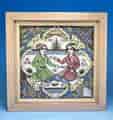

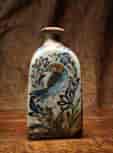

Persian Qajar (Iranian) Ceramics

These colourful ceramics are from Iran, products of the pottery industry that flourished in the Qajar dynasty.

Otherwise known as the ‘Persian’ Empire, the Qajar dynasty controlled parts the area of present-day countries Iraq, Iran, and Afghanistan, as well as the southern parts of Georgia.

The Qajars ruled from 1779 to 1924, coming from Astarabad, south-east of the Caspian Sea. Under the Qajars the capital of this Persia Empire was moved to Tehran.

Selection of Qajar ‘fritware’ vases & tiles: the body is not just fired clay, but rather a ‘glassy’ silica granular slurry of sand and a very minor amount of clay, which fuses when heated, the fused surface keeping the piece structurally sound. If broken, a crumbly sand-like interior is exposed. The example at far right is several centuries earlier, being a fine example of Iznik production of the late 15th/early 16th century. It was on this legacy that the Qajar ceramics built their trade, often imitating much earlier designs.

Qajar tile with horseman & Huma, 19th c.

Tiles were a useful wall covering that was both decorative and durable. Depicted here is perhaps the illustration from a legend – the man on his green-spotted horse appears to feed the circling spectacular bird with the extra large tail. This bird we can identify as a ‘Simurgh’.

The Simurgh – also called Huma – was a mythical bird which flew invisibly above the earth. With no legs, it could not land, and it never cast a shadow – except onto a King. The feathers often seen on a King/Shah/Sultan’s turban represent this divine anointing. It is a mighty and auspicious bird, bringer of great fortune, and features central to the early Persian tales.

It also represents the unattainable – always being unreachable high, perhaps the origin of the saying ‘aiming for the sky’.

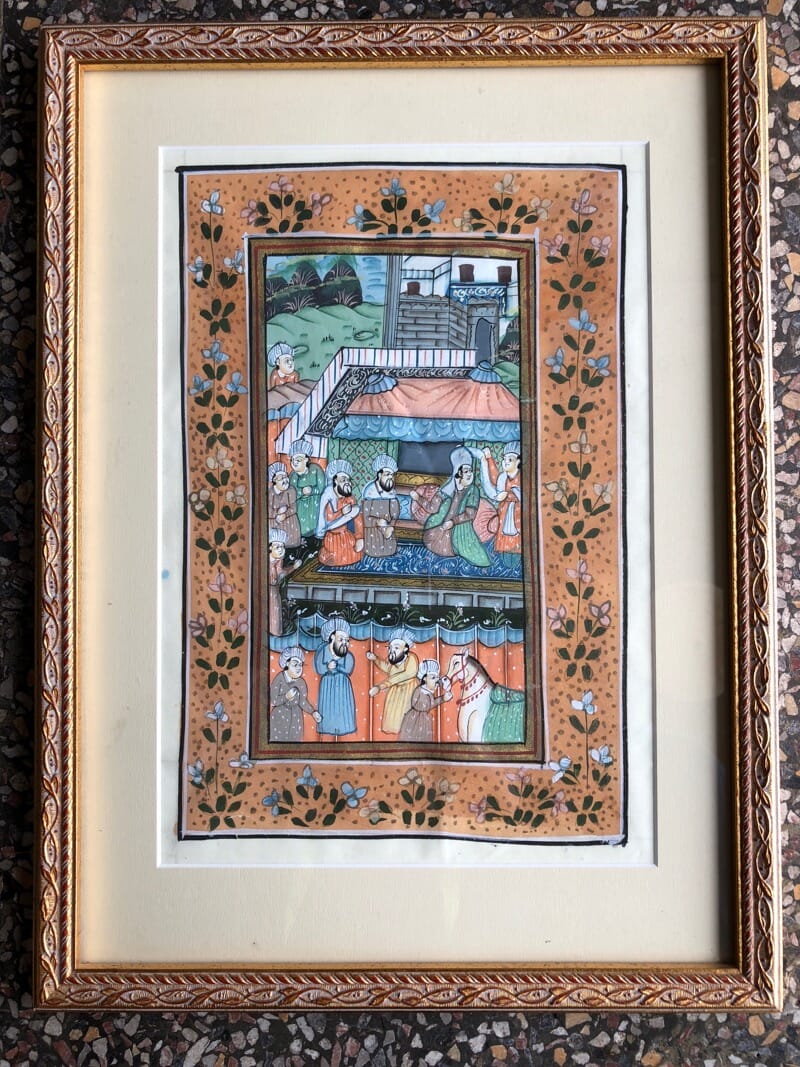

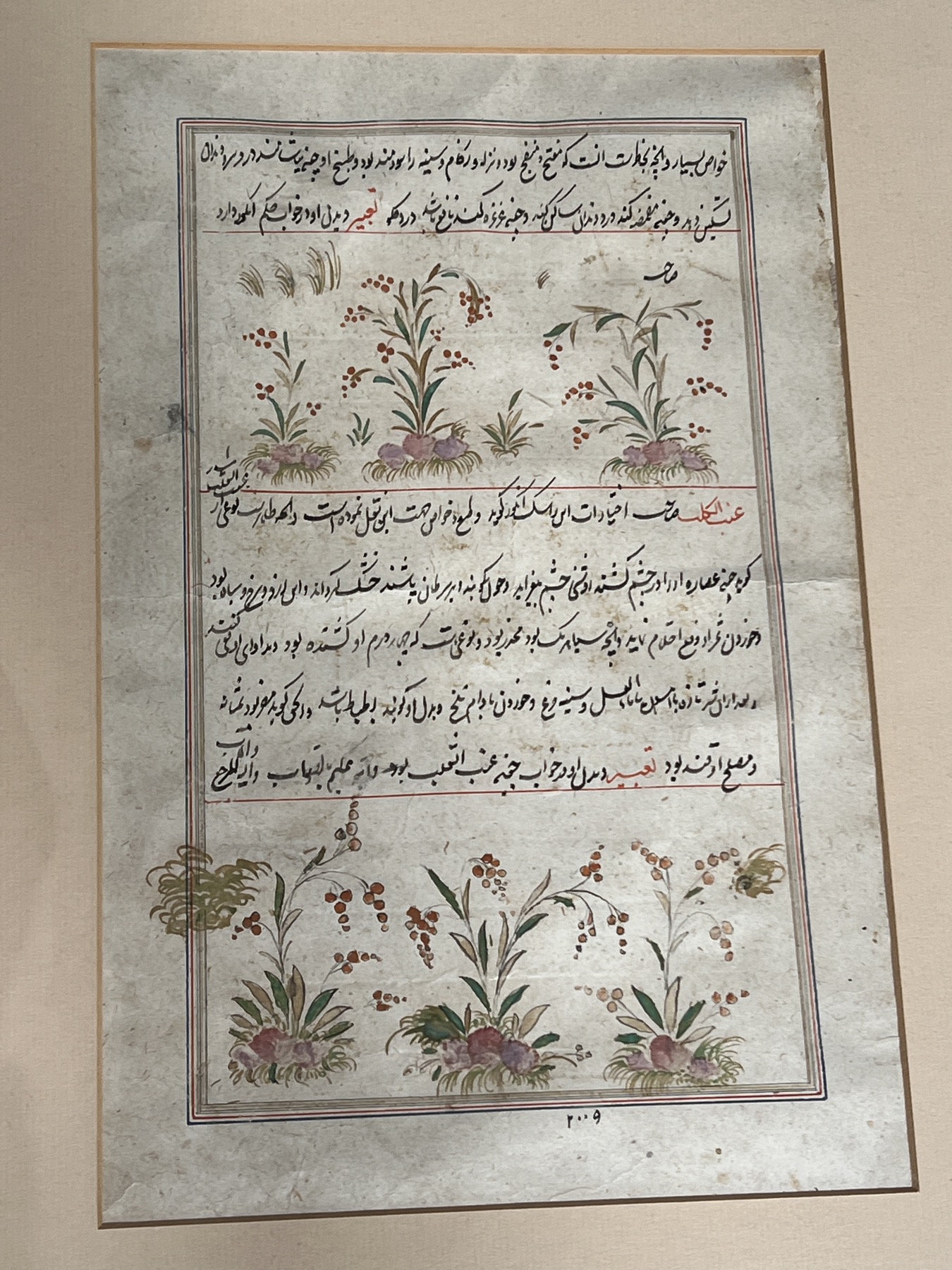

Persian ‘Kitab-i hasha’ish’ – the Materia Medica of Dioscurides, Botanical Medical manuscript

This Persian manuscript page is a fascinating example of how the Islamic World preserved ancient knowledge during Europe’s so-called ‘Dark Ages’. It is from a ‘Kitab-i hasha’ish‘ – the ‘Materia Medica’ of Dioscurides, a 1st century AD physician of Greek origin, who had compiled the botanical medicinal knowledge of the period into a series of books. Originally in Greek, they were preserved through constant copying complete with illustrations in the Islamic world. They drew on all knowledge of the time, and Dioscurides claimed to have travelled far & wide as a physician with the Roman Army. This example has an illustration of an unknown bulb with groups of red flowers, the text explaining the usage of various components for various ailments, in flowing Persian calligraphy with important words in red. It is set within a frame of gold / black / red / blue carefully ruled lines, a style that appears on items originating in Isfahan, Iran – although they were made right across the Islamic world for many centuries, from the earliest in Baghdad in the 10th century to Morocco and India right into the 19th century.

This page is attributed to one from the 17th – 18th century.

Fresh Middle-Eastern stock

-

Persian Qajar period reverse-painted mirror, bird & iris, later 19th century$495.00 AUD

Persian Qajar period reverse-painted mirror, bird & iris, later 19th century$495.00 AUD -

Persian Qajarperiod tile, hunt scene, green tones, early 20th c.$290.00 AUD

Persian Qajarperiod tile, hunt scene, green tones, early 20th c.$290.00 AUD -

Persian manuscript page from ‘Kitab-i hasha’ish’ – the Materia Medica of Dioscurides, 17th-18th c. medical botany manuscript$780.00 AUD

Persian manuscript page from ‘Kitab-i hasha’ish’ – the Materia Medica of Dioscurides, 17th-18th c. medical botany manuscript$780.00 AUD -

Large bronze basin with Islamic inscriptions, Seljuk period, 13th century$3,500.00 AUD

Large bronze basin with Islamic inscriptions, Seljuk period, 13th century$3,500.00 AUD -

Very Large Henry Salt Aquatint, ‘The Pyramids at Cairo’ Egyptian view, published 1809$4,950.00 AUD

Very Large Henry Salt Aquatint, ‘The Pyramids at Cairo’ Egyptian view, published 1809$4,950.00 AUD -

Very Large Henry Salt Aquatint, ‘View over Grand Cairo’ Egyptian view, published 1809$4,950.00 AUD

Very Large Henry Salt Aquatint, ‘View over Grand Cairo’ Egyptian view, published 1809$4,950.00 AUD -

Persian Qajar period tile, figures eating, Iran 19th c.$540.00 AUD

Persian Qajar period tile, figures eating, Iran 19th c.$540.00 AUD -

Persian Qajar tile, horseman in landscape, 19th c.Sold

Persian Qajar tile, horseman in landscape, 19th c.Sold -

Persian Qajar Dynasty tri-sided fritware vase with polychrome panels of birds and flowers, c.1900$480.00 AUD

Persian Qajar Dynasty tri-sided fritware vase with polychrome panels of birds and flowers, c.1900$480.00 AUD -

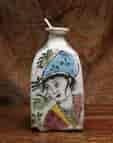

Persian Qajar Dynasty tri-sided vase with polychrome panels of flowers and portrait, c.1900$645.00 AUD

Persian Qajar Dynasty tri-sided vase with polychrome panels of flowers and portrait, c.1900$645.00 AUD -

Persian Qajar Dynasty tile, horseman & huge bird, ‘Simurgh’, later 19thc.$580.00 AUD

Persian Qajar Dynasty tile, horseman & huge bird, ‘Simurgh’, later 19thc.$580.00 AUD -

Persian Qajar fritware vase, unusual triangular form, c. 1900Sold

Persian Qajar fritware vase, unusual triangular form, c. 1900Sold -

Persian vessel with head of a ruler, Qajar Dynasty of Iran, c. 1880$480.00 AUD

Persian vessel with head of a ruler, Qajar Dynasty of Iran, c. 1880$480.00 AUD -

Product on sale

Iranian ‘Qalamzani’ charger, by Master Mahdi Alamdari , 1970’sOriginal price was: $2,200.00 AUD.$1,500.00 AUDCurrent price is: $1,500.00 AUD.

Iranian ‘Qalamzani’ charger, by Master Mahdi Alamdari , 1970’sOriginal price was: $2,200.00 AUD.$1,500.00 AUDCurrent price is: $1,500.00 AUD. -

Egyptian coin souvenir spoon – jewelled crescent moon – c. 1920$35.00 AUD

Egyptian coin souvenir spoon – jewelled crescent moon – c. 1920$35.00 AUD -

Damascus ware charger, superb silver & gold Mamluk Revival inlay, Kufic script, c. 1900$2,750.00 AUD

Damascus ware charger, superb silver & gold Mamluk Revival inlay, Kufic script, c. 1900$2,750.00 AUD -

Turkish .800 coffee set, cezve, boxes & 4 cups, kufic inscriptions, c. 1900Sold

Turkish .800 coffee set, cezve, boxes & 4 cups, kufic inscriptions, c. 1900Sold -

Middle Eastern silver ‘Torc’ shaped bangleSold

Middle Eastern silver ‘Torc’ shaped bangleSold -

Egyptian silver lidded coffee pot, engine-turned body & flower knop, Sultan Abdulaziz c.1870Sold

Egyptian silver lidded coffee pot, engine-turned body & flower knop, Sultan Abdulaziz c.1870Sold -

Palestinian Silver brooch with camels and palm tree, c.1910Sold

Palestinian Silver brooch with camels and palm tree, c.1910Sold -

Palestinian .935 silver filigree necklace, c.1910Sold

Palestinian .935 silver filigree necklace, c.1910Sold -

Blue Glass Rosewater sprinkler, French 19th century$295.00 AUD

Blue Glass Rosewater sprinkler, French 19th century$295.00 AUD -

Glass rosewater bottle with cut and gilt decoration$525.00 AUD

Glass rosewater bottle with cut and gilt decoration$525.00 AUD -

Persian fritware jar, Oriental style, 17th century$1,250.00 AUD

Persian fritware jar, Oriental style, 17th century$1,250.00 AUD -

Iranian Silver & Glass coffee cup, head of a ruler, Qajar, 19th c.$580.00 AUD

Iranian Silver & Glass coffee cup, head of a ruler, Qajar, 19th c.$580.00 AUD