Welcome to our Fresh Stock Directory.

Everyone’s looking for something different – so we have divided it up into areas of interest: choose a ‘Gallery’ below to browse the latest items of that type to be uploaded.

Latest Fresh Stock Release Blogs

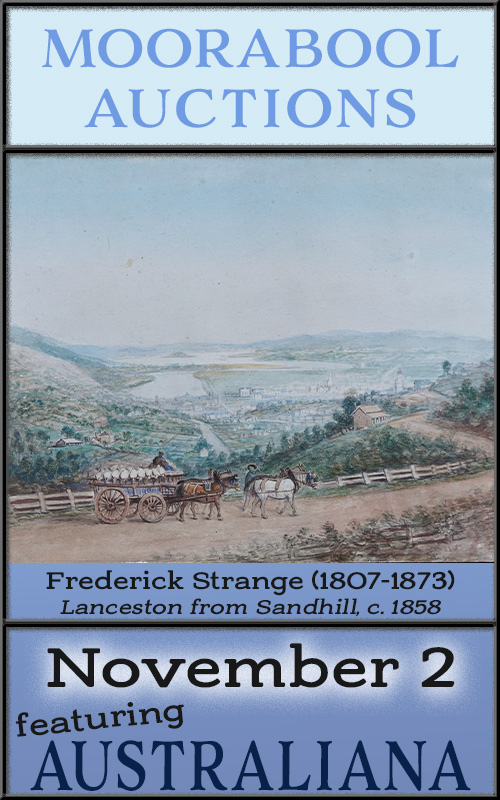

- Fresh Stock at Moorabool

Welcome to our latest Fresh Stock release. There’s quite a range of Fresh items to browse…. Here’s our new way of browsing: enjoy!

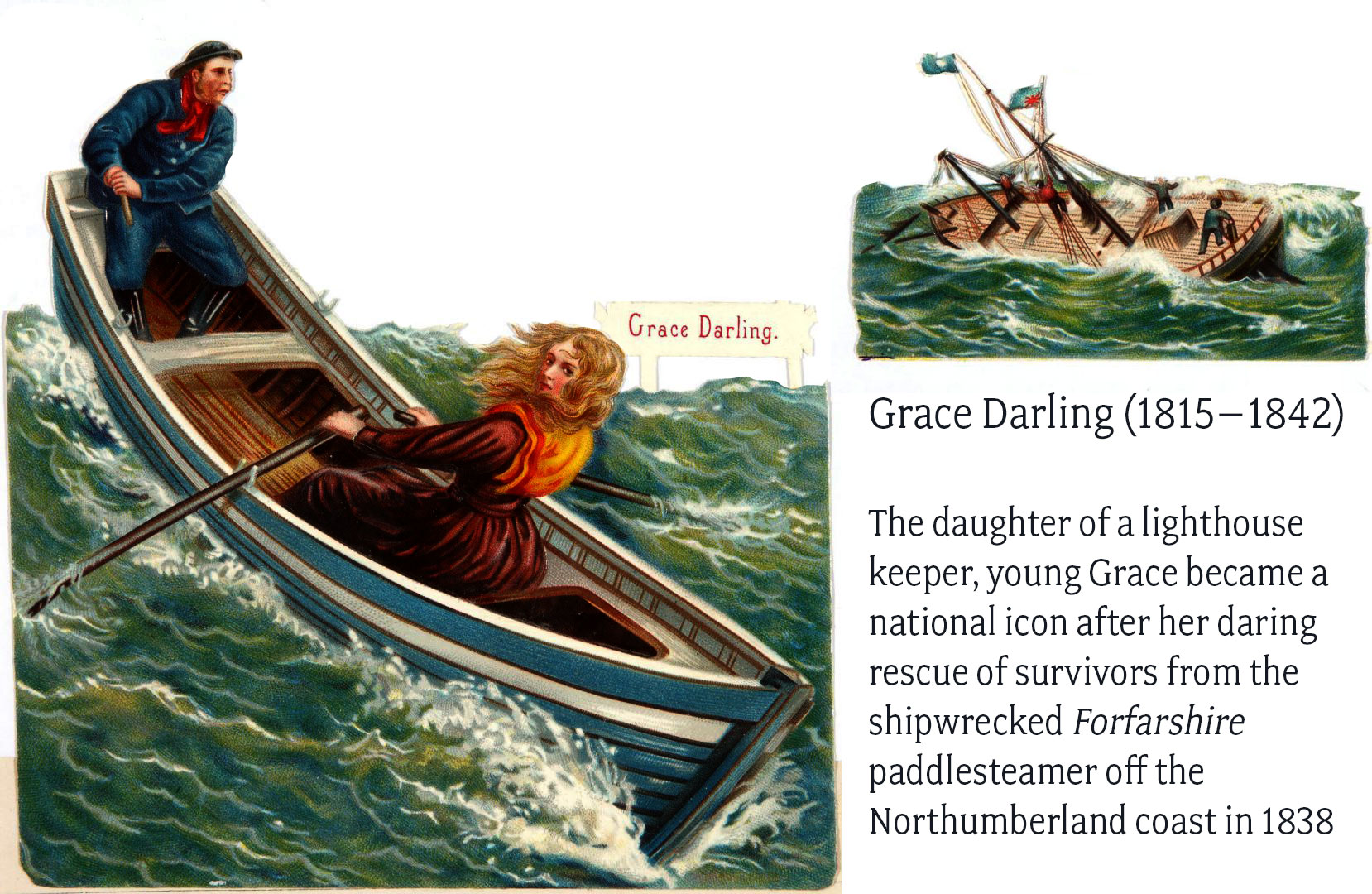

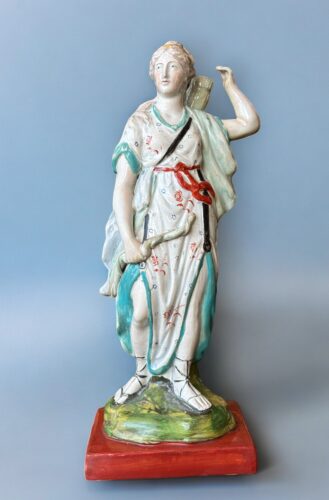

Welcome to our latest Fresh Stock release. There’s quite a range of Fresh items to browse…. Here’s our new way of browsing: enjoy! - Grace Darling, the Heroine of the Sea – in Staffordshire!

Grace Darling, the heroic lighthouse-keeper’s daughter is the subject of this rare Staffordshire figure fresh to Moorabool’s stock. But something is very peculiar with this example…. making it possibly unique!

Grace Darling, the heroic lighthouse-keeper’s daughter is the subject of this rare Staffordshire figure fresh to Moorabool’s stock. But something is very peculiar with this example…. making it possibly unique! - An Asian-themed Fresh Stock

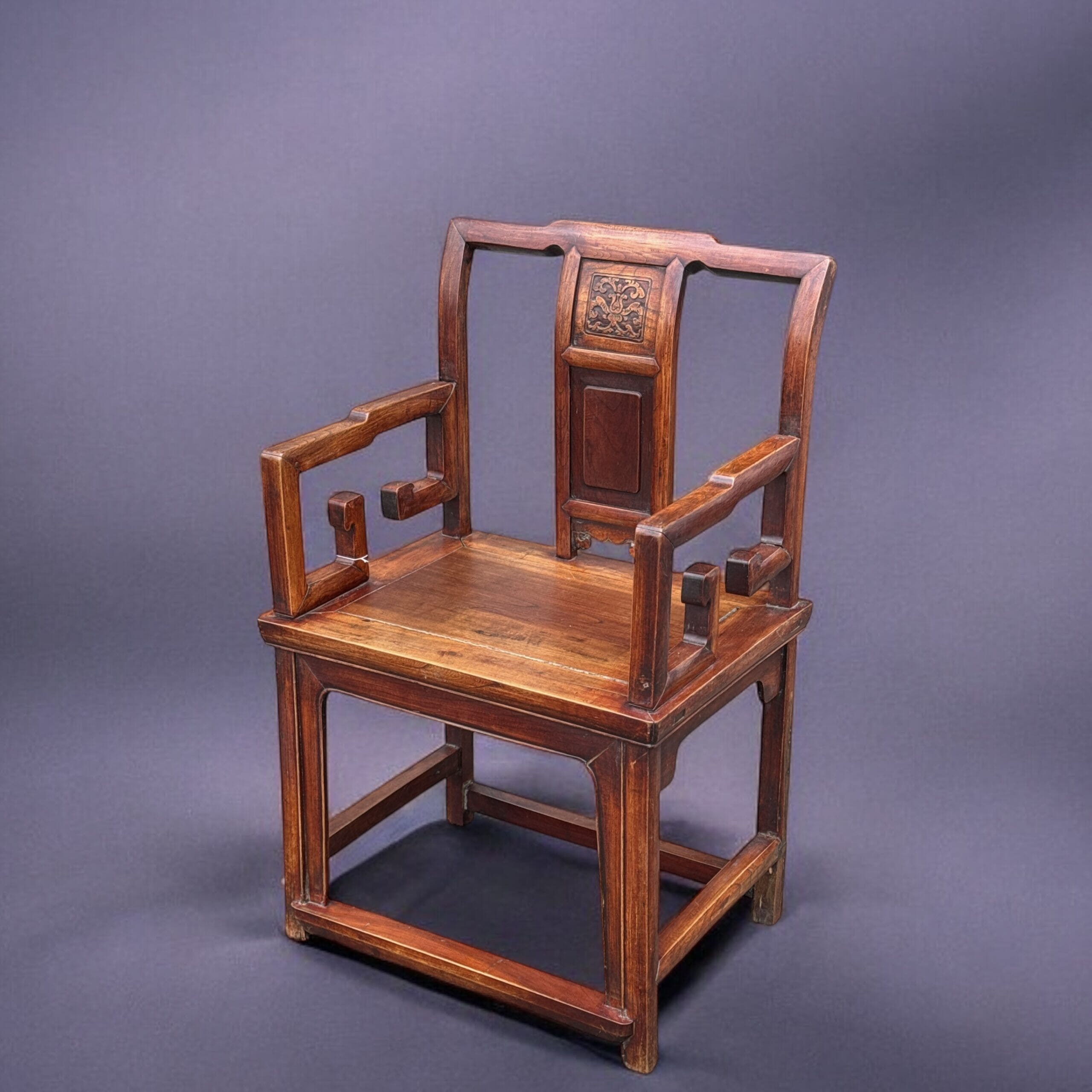

Fresh Stock with an Asian Theme – a good quantity of items for you to browse from China, Japan, Burma, Thailand, and Sri Lanka….

Fresh Stock with an Asian Theme – a good quantity of items for you to browse from China, Japan, Burma, Thailand, and Sri Lanka…. - Fresh stock October 7th

Fresh Stock uploaded to moorabool.com . You’ll find a fine and varied selection, from Georgian Furniture to fine 18th century Porcelain, Australian Pottery, a host of Candlesticks, and interesting Artworks

Fresh Stock uploaded to moorabool.com . You’ll find a fine and varied selection, from Georgian Furniture to fine 18th century Porcelain, Australian Pottery, a host of Candlesticks, and interesting Artworks - Premium Fresh Stock

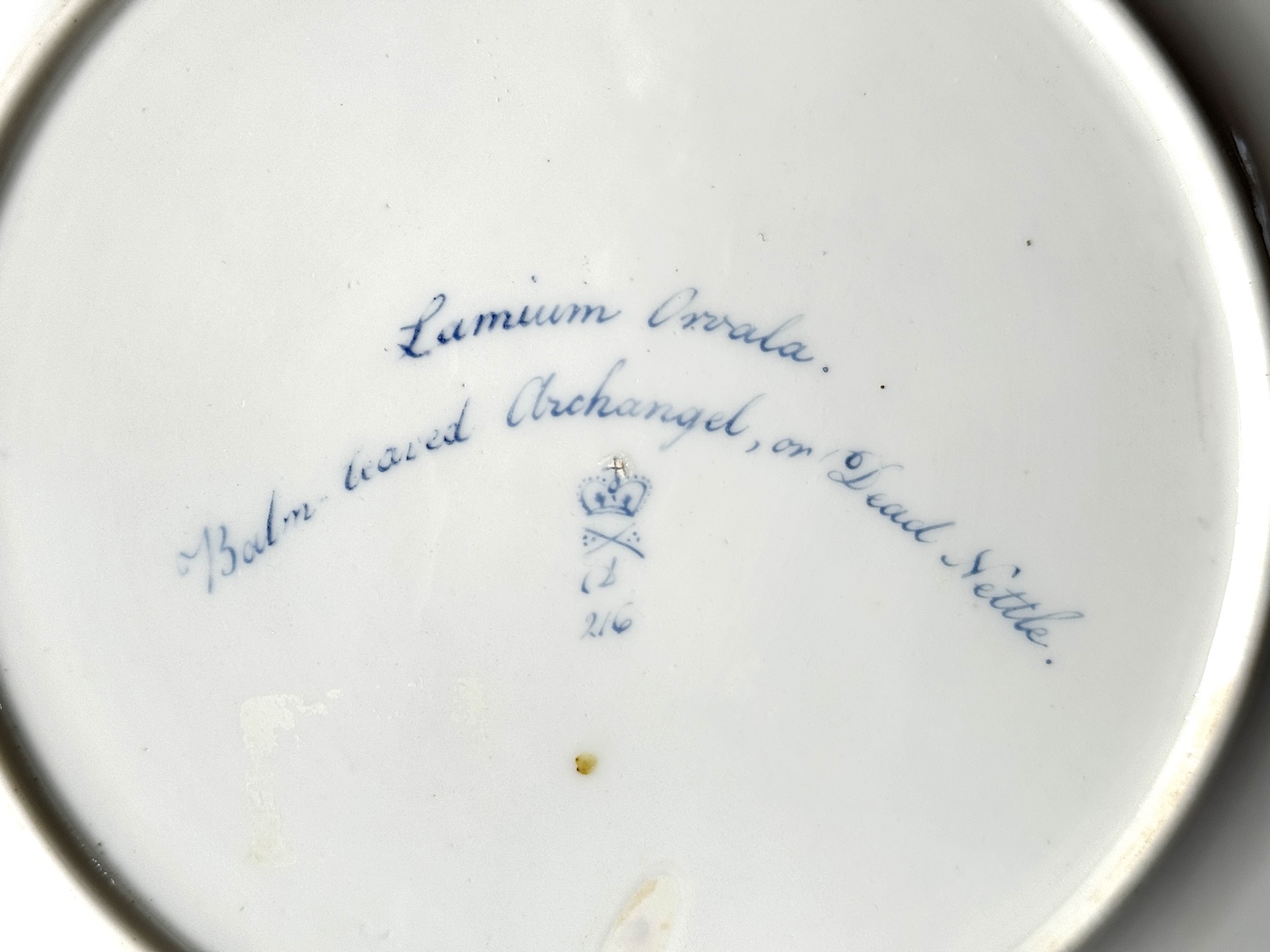

Welcome to our selection of ‘the Best’ for the end of 2024. Some stunning rarities have come to us recently, with many local high-quality collections being dispersed. Enjoy your browse through the following Premium items – with more items being prepared for the near future. Quaker Pegg – “Balm-leaved Archangel” c. 1796 From the English Derby factory comes a piece… Read more: Premium Fresh Stock

Welcome to our selection of ‘the Best’ for the end of 2024. Some stunning rarities have come to us recently, with many local high-quality collections being dispersed. Enjoy your browse through the following Premium items – with more items being prepared for the near future. Quaker Pegg – “Balm-leaved Archangel” c. 1796 From the English Derby factory comes a piece… Read more: Premium Fresh Stock - Derby ‘Adolescent Seasons’

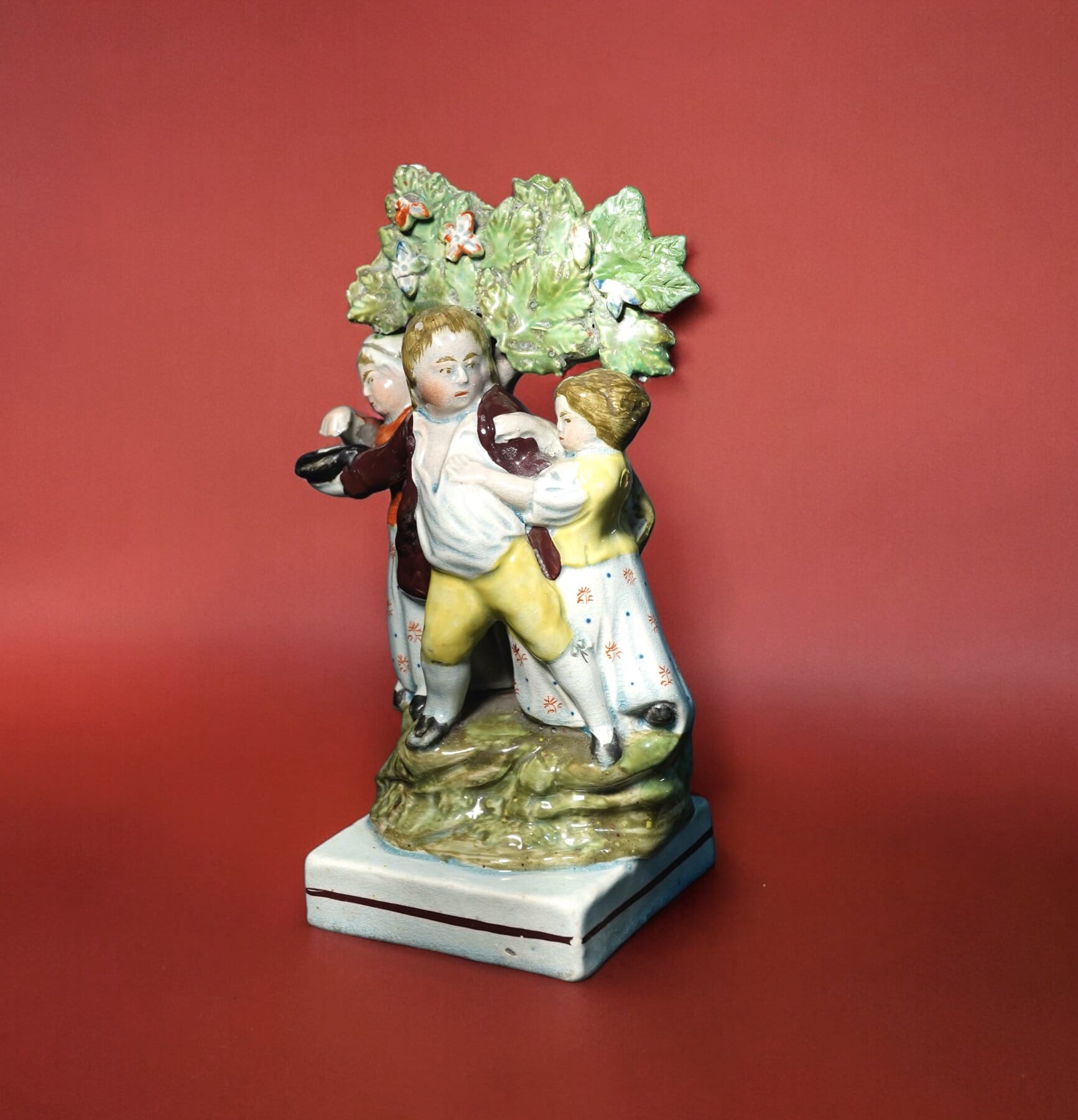

Moorabool has a fascinating group of Derby ‘Seasons’, modelled as children with their respective attributes. They make for an interesting study, and show the development of the classic rococo-based Derby figures of the latter 18th century.

Moorabool has a fascinating group of Derby ‘Seasons’, modelled as children with their respective attributes. They make for an interesting study, and show the development of the classic rococo-based Derby figures of the latter 18th century. - Arts & Crafts Collection

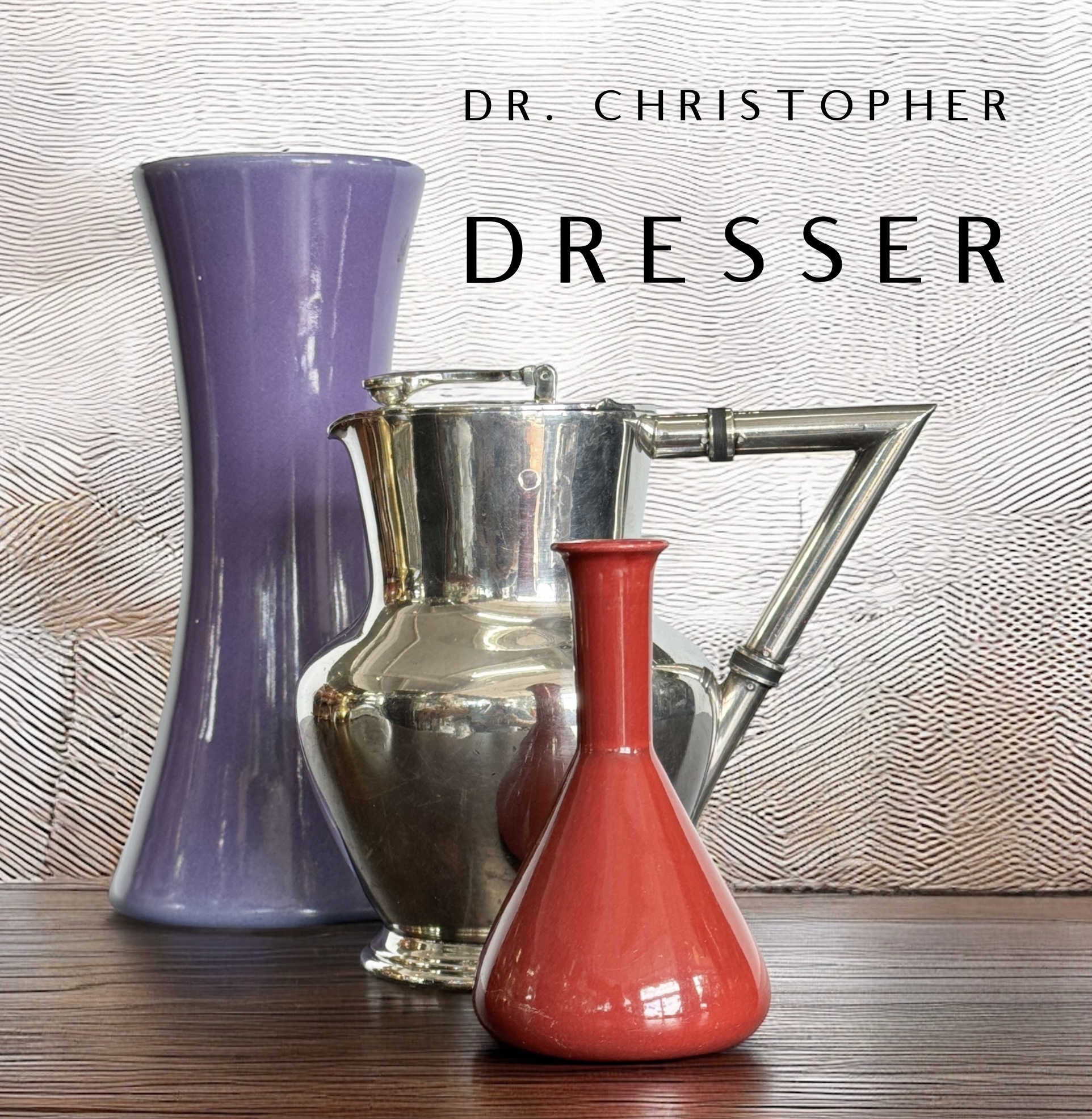

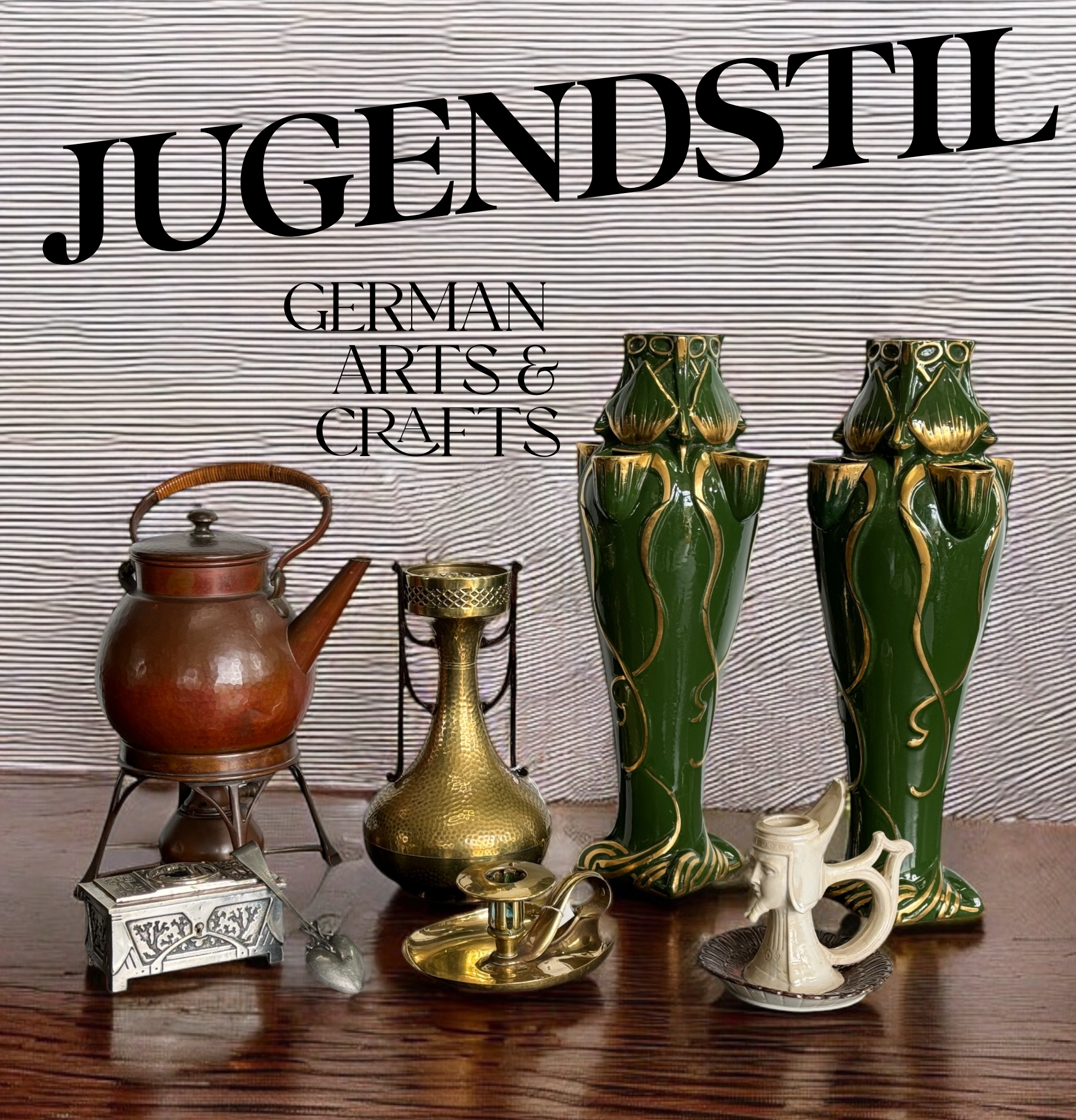

A fine selection of ‘Arts & Crafts’ has just been posted on Moorabool.com . It’s an interesting survey of the late 19th- early 20th century designs that were a reaction against the overly ornate – and predictable – designs of Victorian England. Often borrowing & intermingled, the French Art Nouveau aesthetic blended with the German/Austrian Jugendstil (youthful-style) and even had a major impact on Australian products – although it did take some time to reach us ‘down-under’ !

A fine selection of ‘Arts & Crafts’ has just been posted on Moorabool.com . It’s an interesting survey of the late 19th- early 20th century designs that were a reaction against the overly ornate – and predictable – designs of Victorian England. Often borrowing & intermingled, the French Art Nouveau aesthetic blended with the German/Austrian Jugendstil (youthful-style) and even had a major impact on Australian products – although it did take some time to reach us ‘down-under’ ! - A Staffordshire Fresh Stock

Welcome to our latest Fresh Stock. This one is a ‘Staffordshire Special’, with some early figures dating to the late 18th – early 19th century – as well as a good selection of classic Victorian pieces. There’s a couple of Highwaymen, one titled ‘Dick Turpin’, the other facing horseman traditionally being his companion Gentleman-Robber, ‘Tom King’ (actually Mathew, not Tom….)… Read more: A Staffordshire Fresh Stock

Welcome to our latest Fresh Stock. This one is a ‘Staffordshire Special’, with some early figures dating to the late 18th – early 19th century – as well as a good selection of classic Victorian pieces. There’s a couple of Highwaymen, one titled ‘Dick Turpin’, the other facing horseman traditionally being his companion Gentleman-Robber, ‘Tom King’ (actually Mathew, not Tom….)… Read more: A Staffordshire Fresh Stock - Bookends

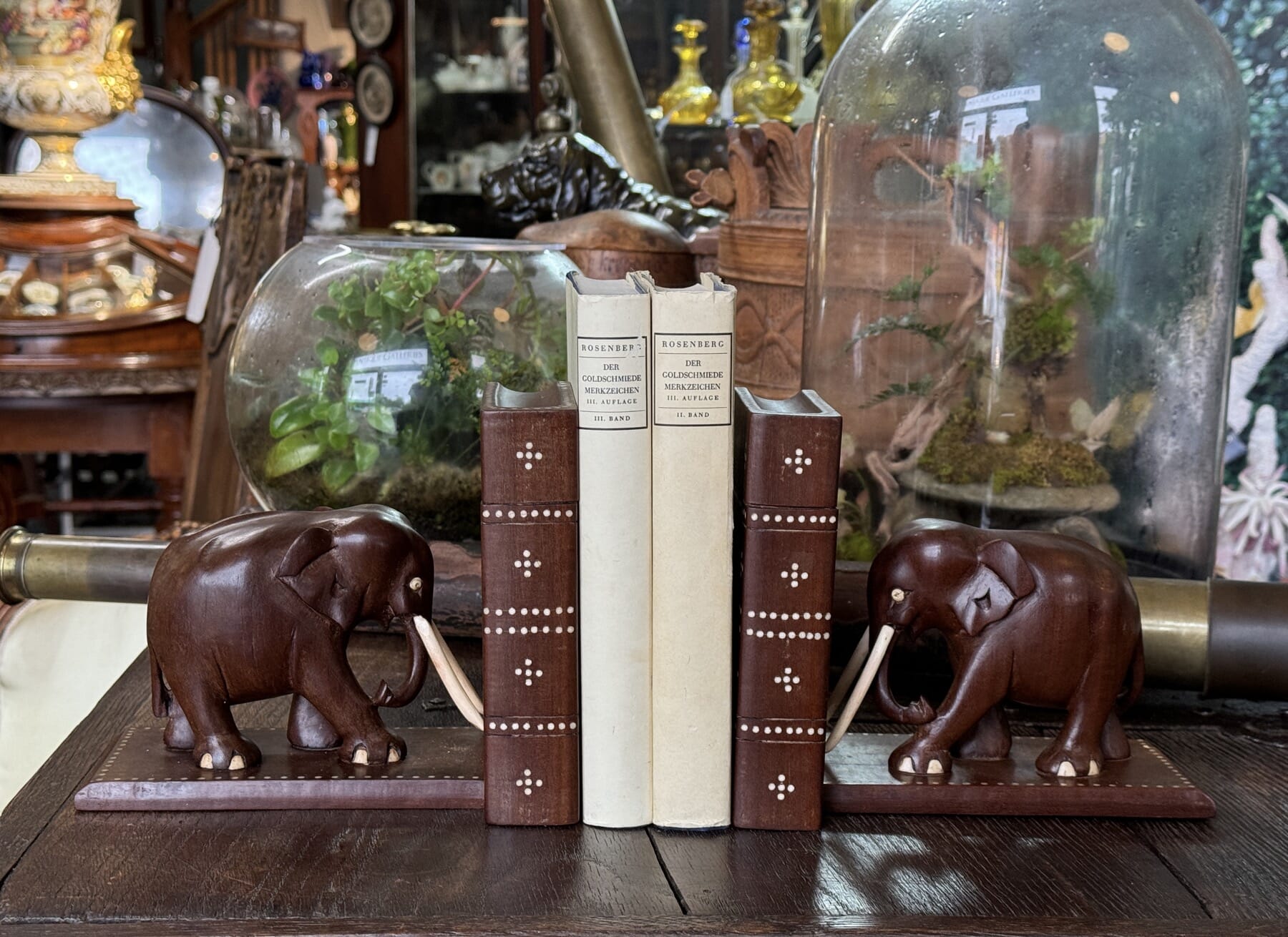

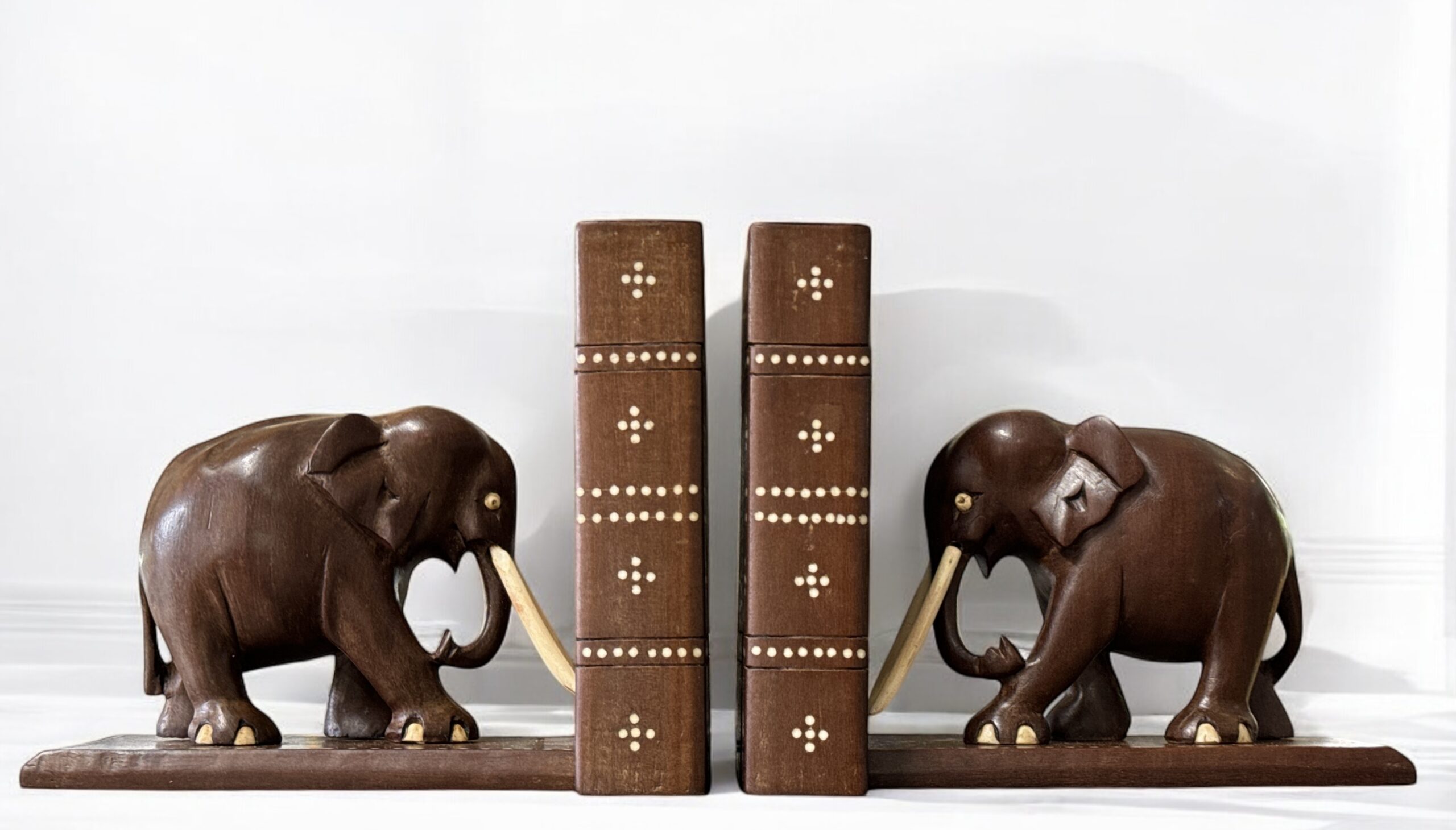

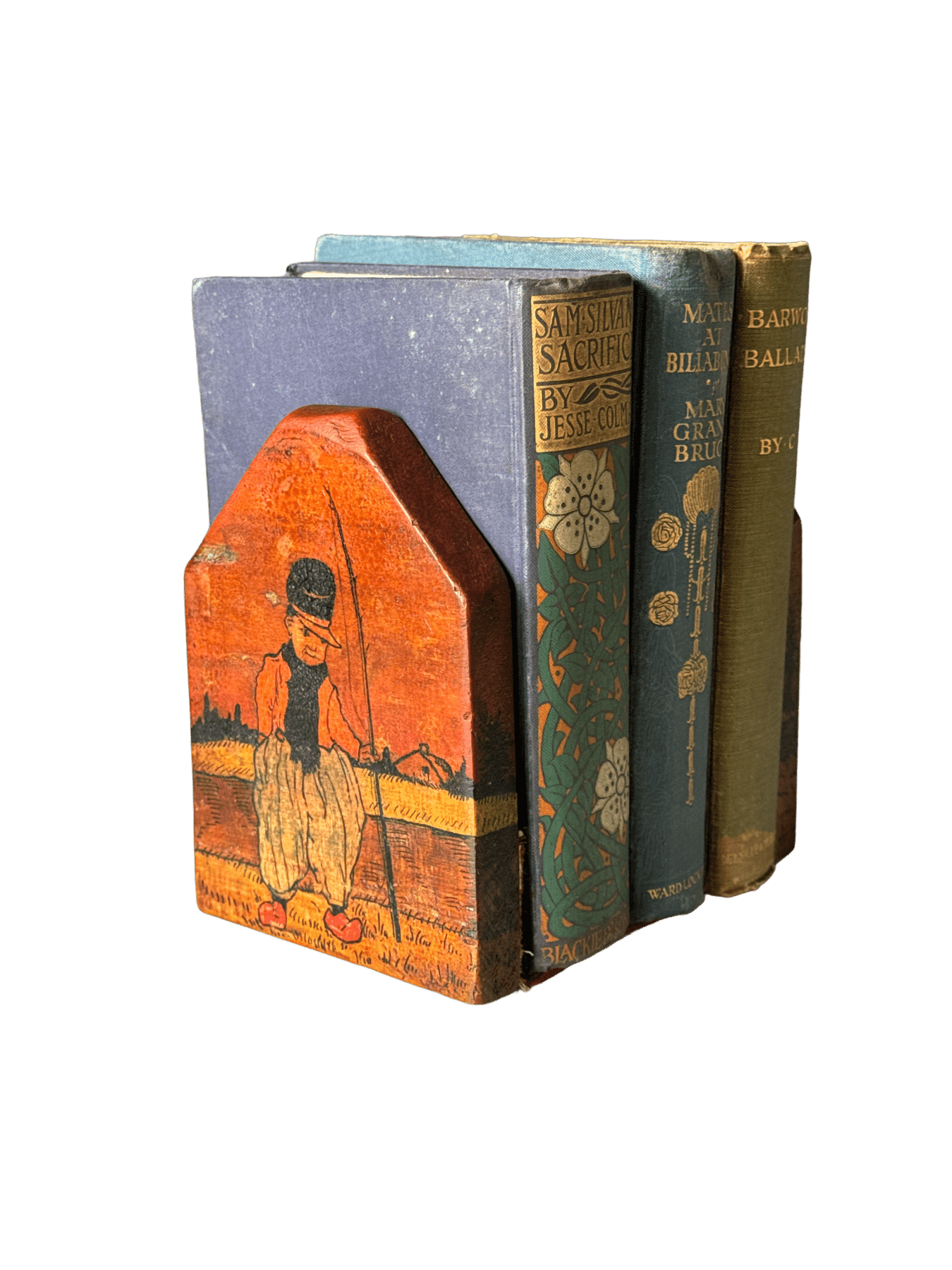

Always handy, and don’t they dress up a bookshelf?

Always handy, and don’t they dress up a bookshelf? - 18th Century English Earthenwares

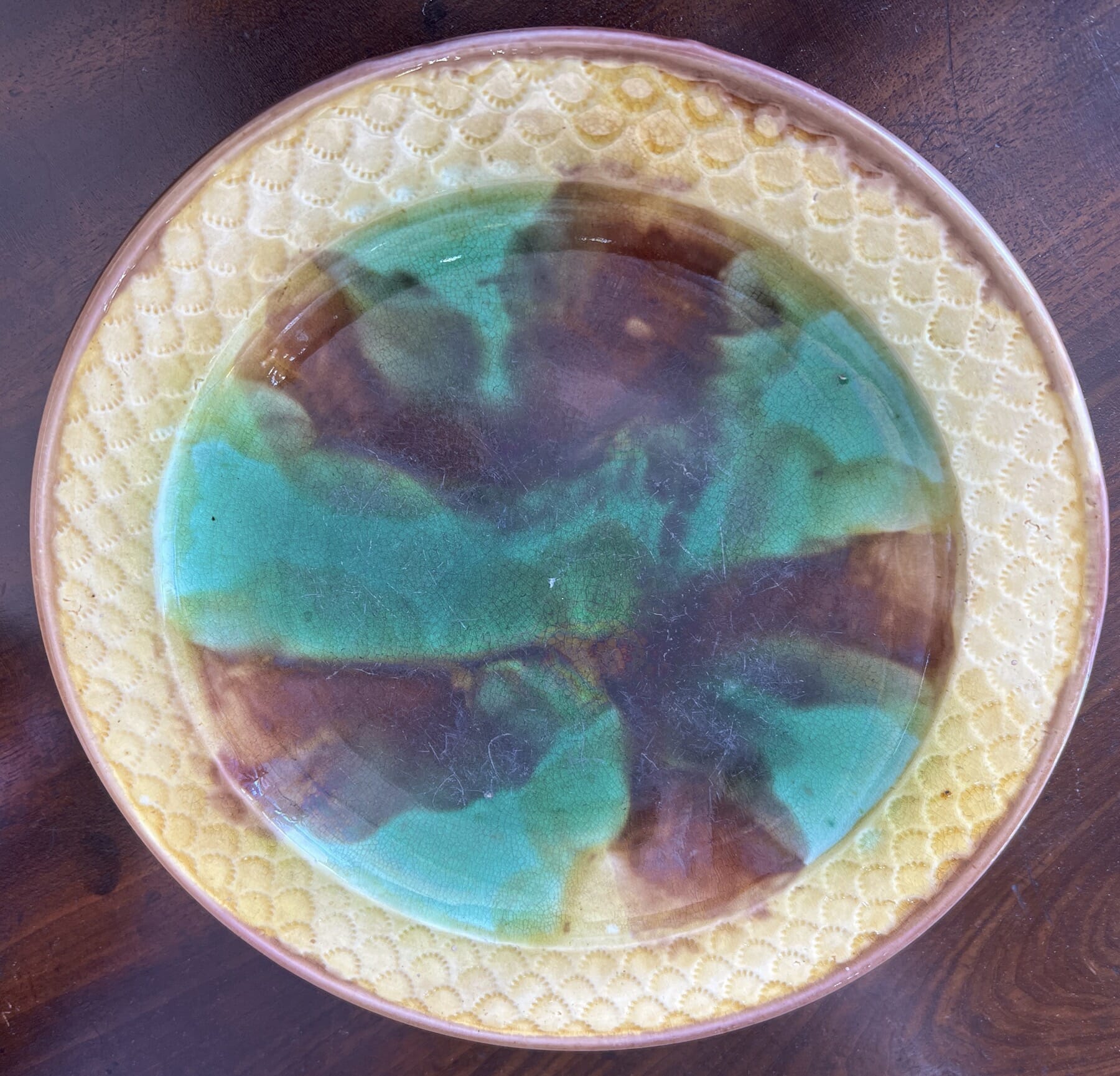

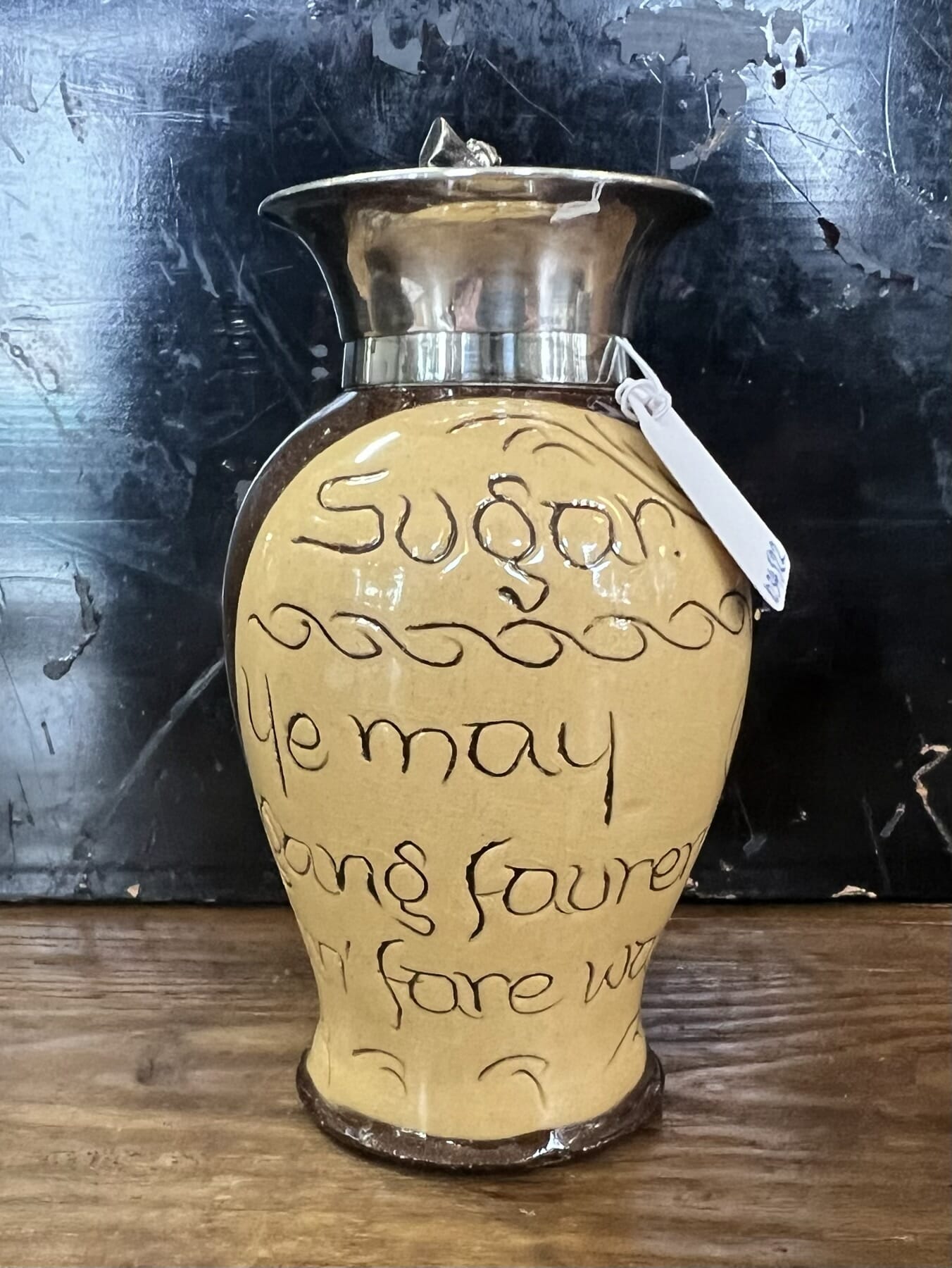

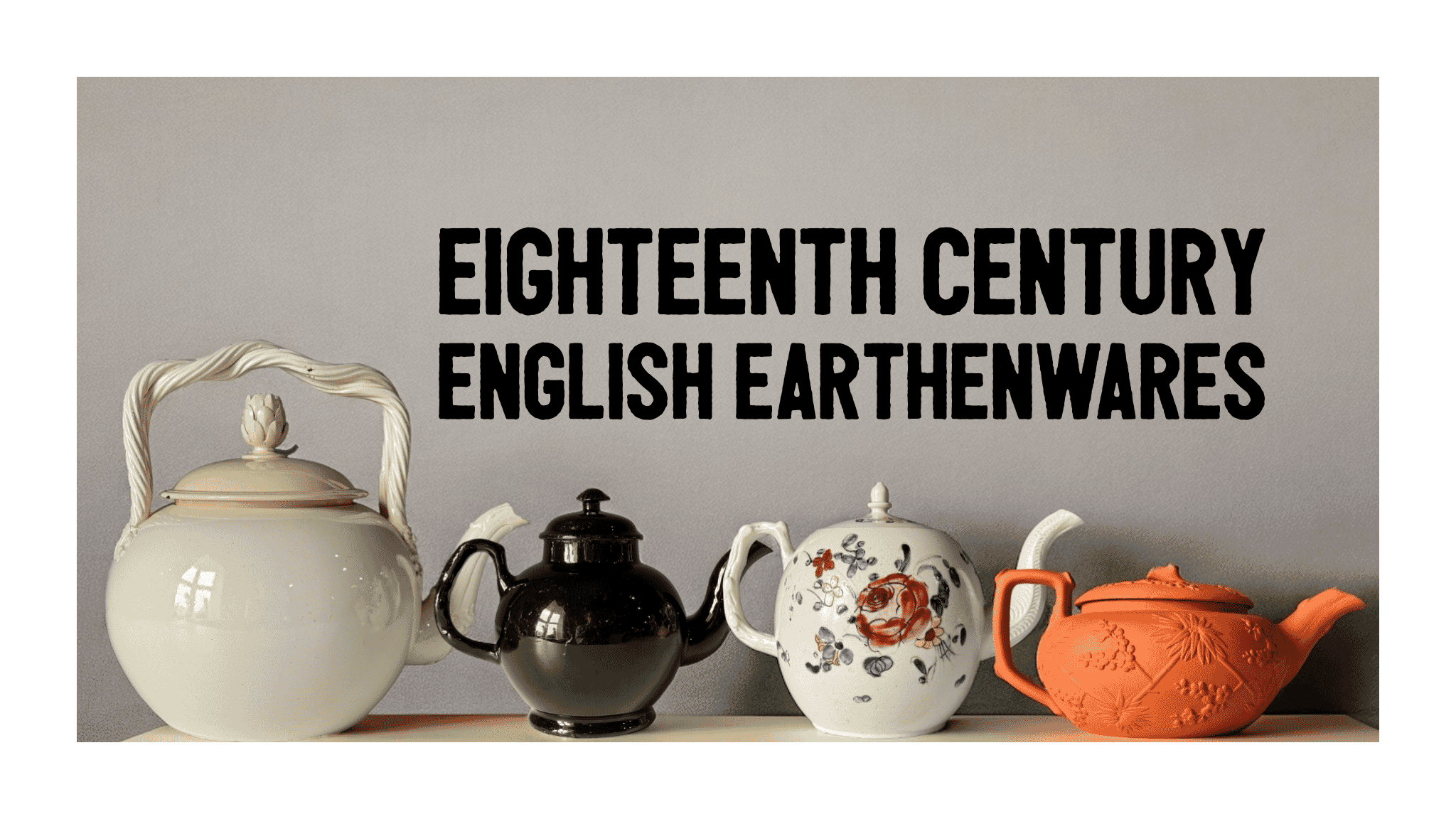

Creamware Creamware is the term for an English earthenware body with a definite ‘cream’ tone, popular in the latter half of the 18th century and replicated across Europe. It emerged from the experimentation of Staffordshire potters seeking a local alternative to expensive Chinese porcelain around 1750. Their innovation yielded a refined cream to white earthenware with a lustrous clear lead… Read more: 18th Century English Earthenwares

Creamware Creamware is the term for an English earthenware body with a definite ‘cream’ tone, popular in the latter half of the 18th century and replicated across Europe. It emerged from the experimentation of Staffordshire potters seeking a local alternative to expensive Chinese porcelain around 1750. Their innovation yielded a refined cream to white earthenware with a lustrous clear lead… Read more: 18th Century English Earthenwares