Old Sheffield Plate teapot with gadrooned half body and gadroon & leaf border, wooden handle, circa 1835.

Re-purposed in 1929 as a cattle Trophy Prize for the Royal Melbourne Show, inscribed as follows;

THE FRANK REYNOLDS MEMORIAL TROPHY / presented by AUSTRALIAN HEREFORD SOCIETY / best pair of yearling Bulls, MELBOURNE ROYAL SHOW 1929 / won by Mrs J BIDDLECOMBE / Golf Hill Royal Standard, Golf Hill Royal Sceptre.

[yith_wc_productslider id=”57794″ z_index=””]

Mrs Janet Biddlecombe (1867-1954) was the daughter of George Russell, the well known settler who was one of the earliest in Victoria, claiming his ‘squat’ at Shelford (just north of Geelong) in 1836 and naming it ‘Golf Hill’. She was a private person who refused to let her gifts to charity be published – but was clearly a great patron of many things. In the last year of her life, she donated the contents of the historic ‘Golf Hill’ to the National Gallery of Victoria, and also many items to the Geelong Art Gallery. (An auction to clear the remainder was held in 1955, attended by a very young John Rosenberg!)

Janet Biddlecombe was the youngest daughter of eight children, and when the property passed to a brother who proved incapable of maintaining it, she was able to assume control. She married several years later, to an English born Navy officer; they had no children. After his death in 1929, she continued to run the station, and attained the highest standards with her livestock. At the Royal Melbourne Show & the Royal Easter Show, Sydney, she consistently won every prize in her division – including this lovely teapot, repurposed from a 100 year old English piece for the purpose. Interestingly, the teapot was made in England at about the same time her father came to Port Phillip as one of the first settlers….

See this piece of local history on our website here >>

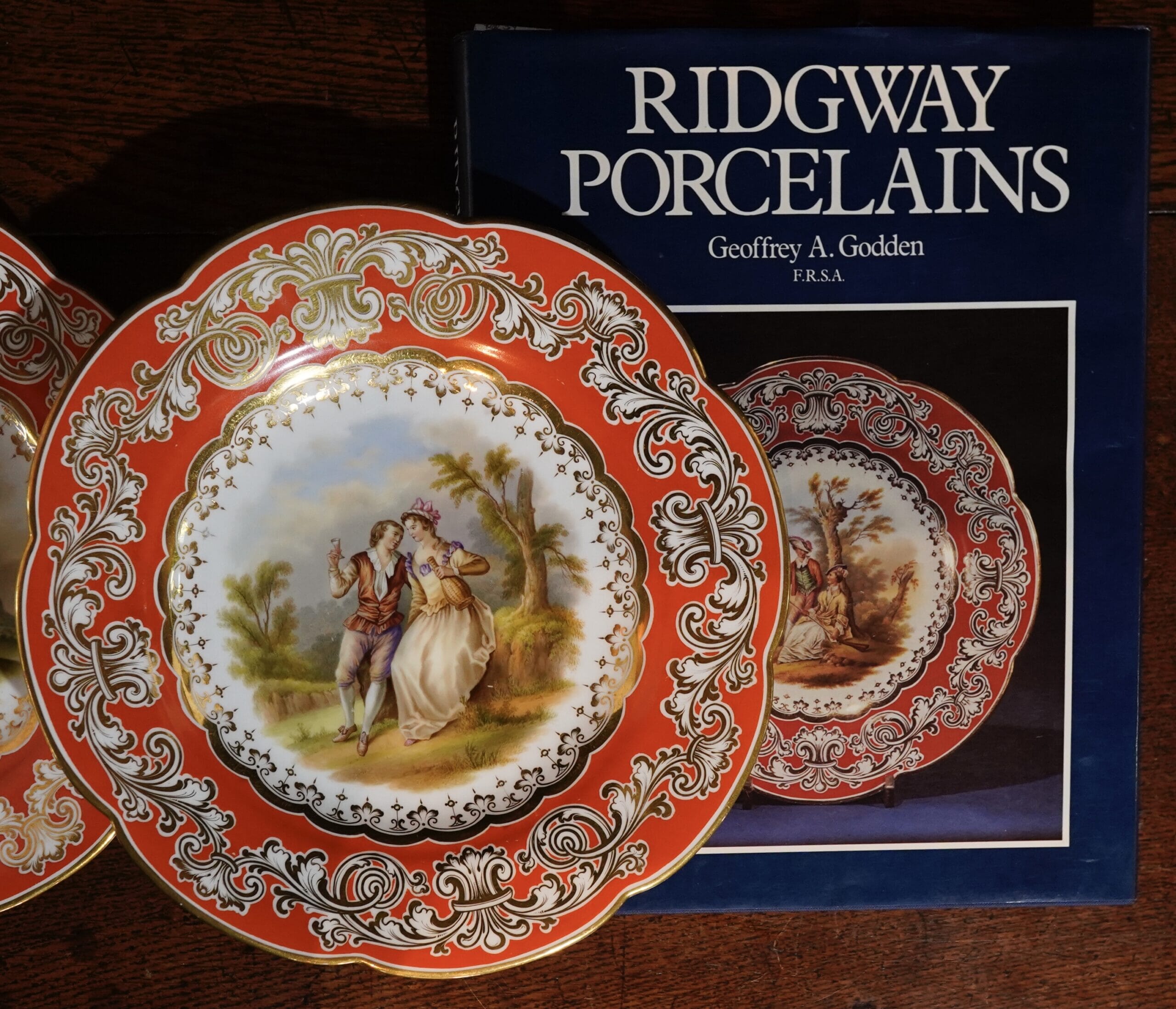

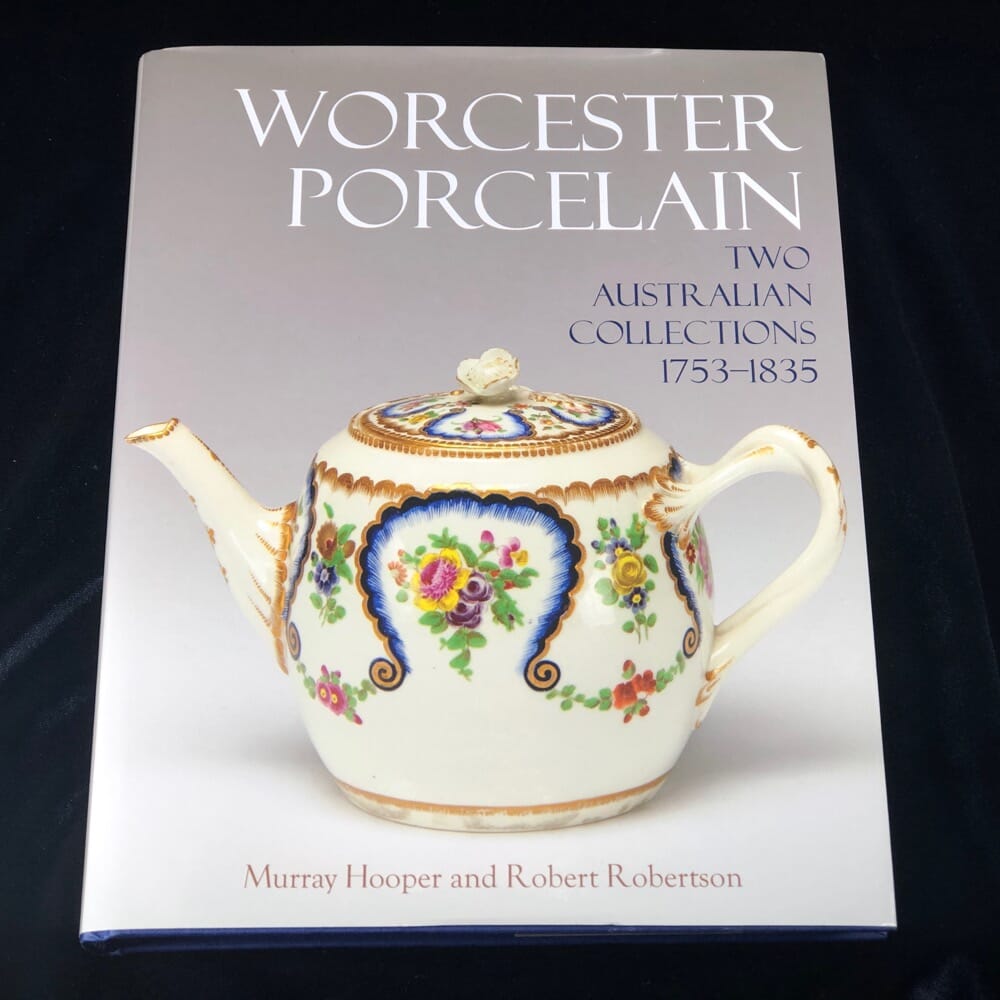

There’s 171 items beautifully photographed, with a useful appendix with visual references to any marks the pieces have. For any dealer or collector, these marks are the essential clue for dating and attribution – but are left out in far too many ‘collectors books’.

There’s 171 items beautifully photographed, with a useful appendix with visual references to any marks the pieces have. For any dealer or collector, these marks are the essential clue for dating and attribution – but are left out in far too many ‘collectors books’. What is refreshing is the inspiration this collection provides for anyone aspiring to do the same; the pieces range from the comparatively ‘common’ (ie. affordable) blue & white florals of the Mansfield pattern, through to some delicious Chinoiseries of the early 1750’s …. some which were once with Moorabool at quite substantial prices….

What is refreshing is the inspiration this collection provides for anyone aspiring to do the same; the pieces range from the comparatively ‘common’ (ie. affordable) blue & white florals of the Mansfield pattern, through to some delicious Chinoiseries of the early 1750’s …. some which were once with Moorabool at quite substantial prices….