Australia became a Nation in 1901, but it was a long process that made this possible. The six far-flung colonies had each developed in their separate ways, and it was the perseverance of Sir Henry Parkes that brought them together. He deserves the title ‘The Father of Federation’.

Moorabool has recently discovered two items that relate to Sir Henry Parkes and his wife, Lady Parkes.

The first is a cast-iron plaque showing a portrait of a bearded gentleman. Mounted onto a turned cowrie pine back, it is typical of the Victorian plaques of notable people, made in large numbers to adorn public buildings like halls and libraries. This example is identified around the edge as ‘SIR Henry Parkes’.

HOWEVER…. it’s actually a terrific example of Aussie ingenuity.

You see, this is not intended as a portrait of Sir Henry Parkes – rather, it was cast in Britain in the 1860’s-70’s as the literary giant, Charles Dickens – who sported a similar magnificent beard and wild hair. Imported into Australia, and perhaps displayed on a library wall somewhere, when Sir Henry Parkes rose to fame in the latter 19th century, an enterprising scholar has added the inscription to make it the ‘Father of Federation’!

Henry Parkes, Fancy Goods & Toy Seller

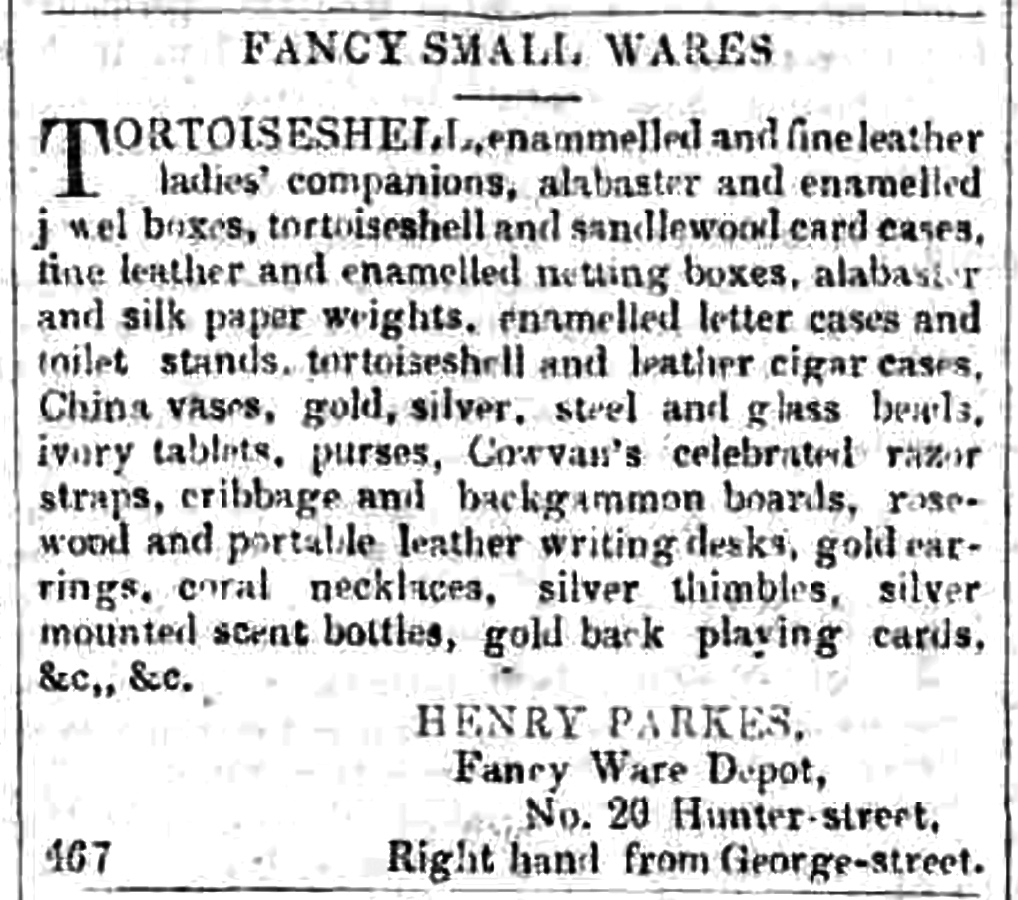

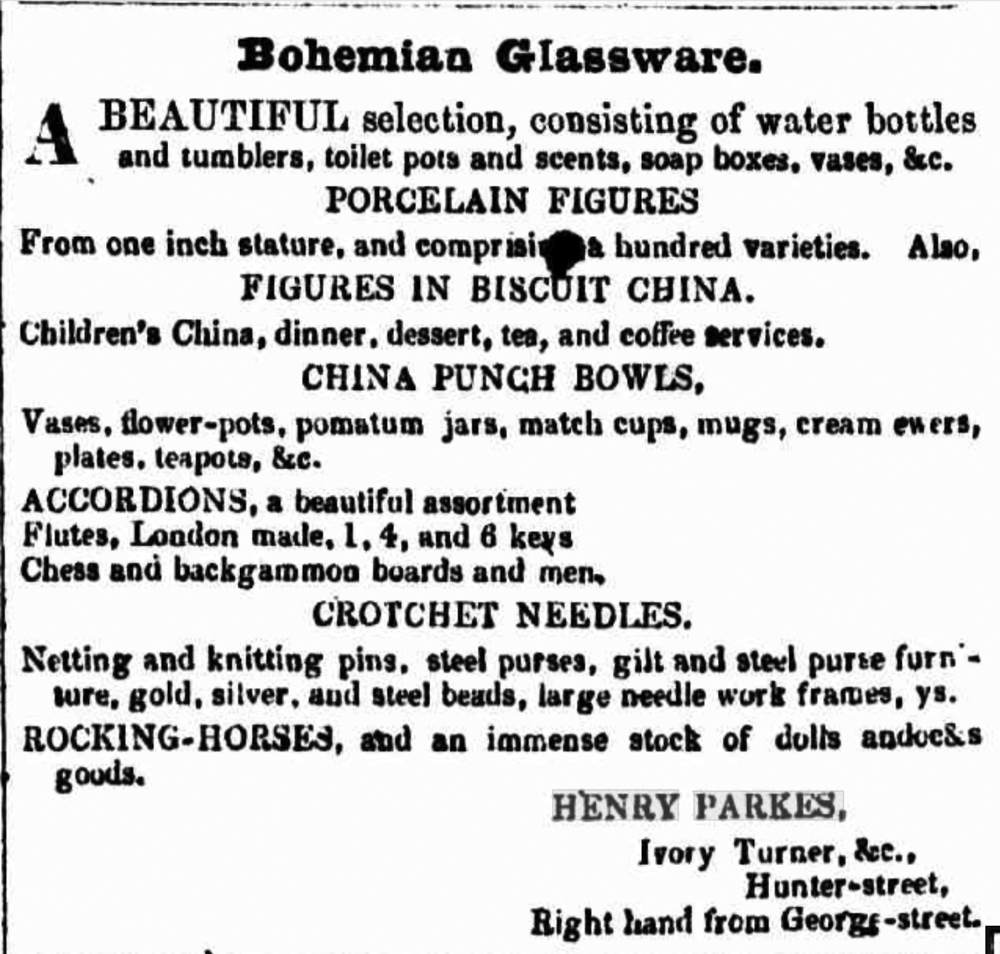

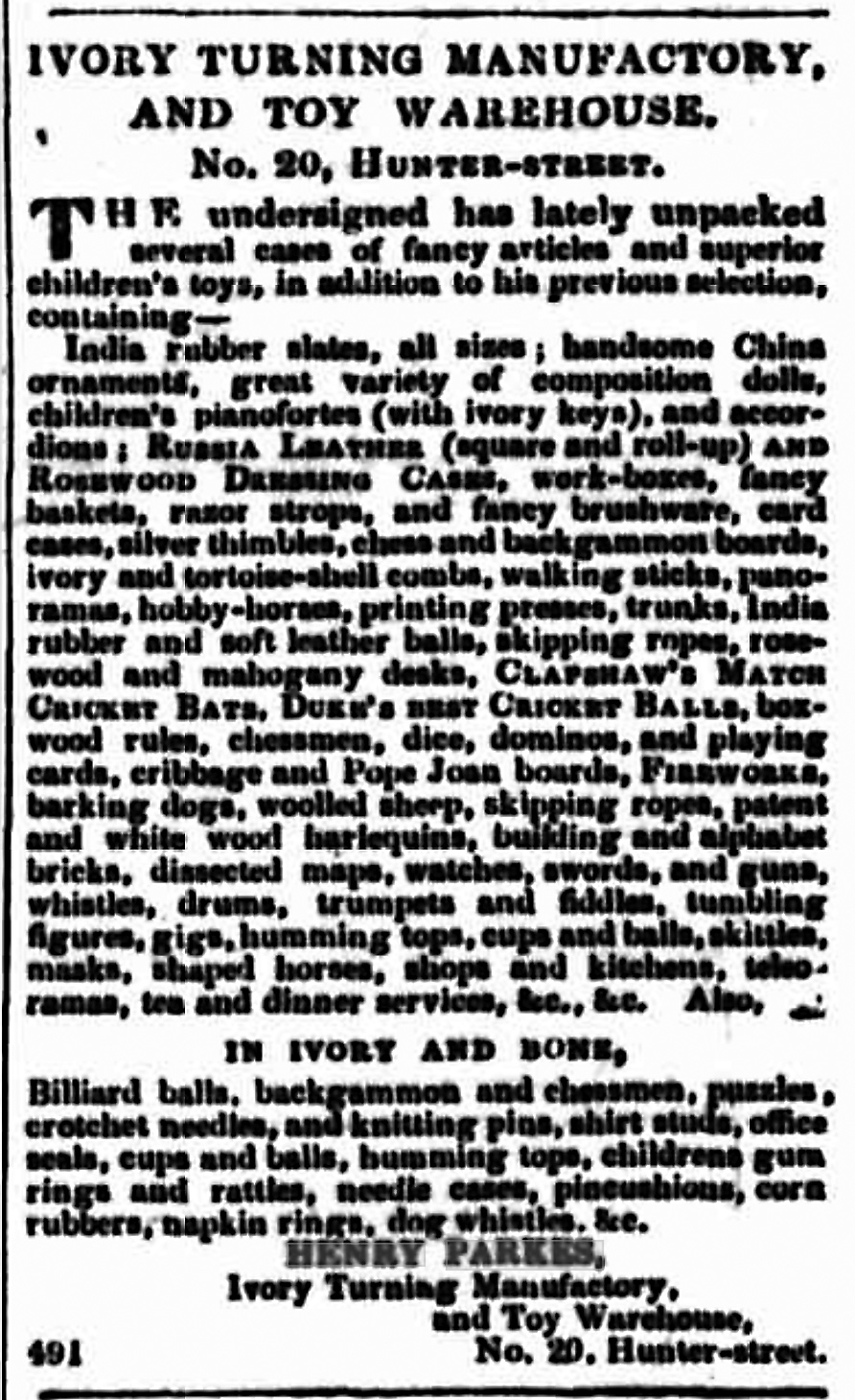

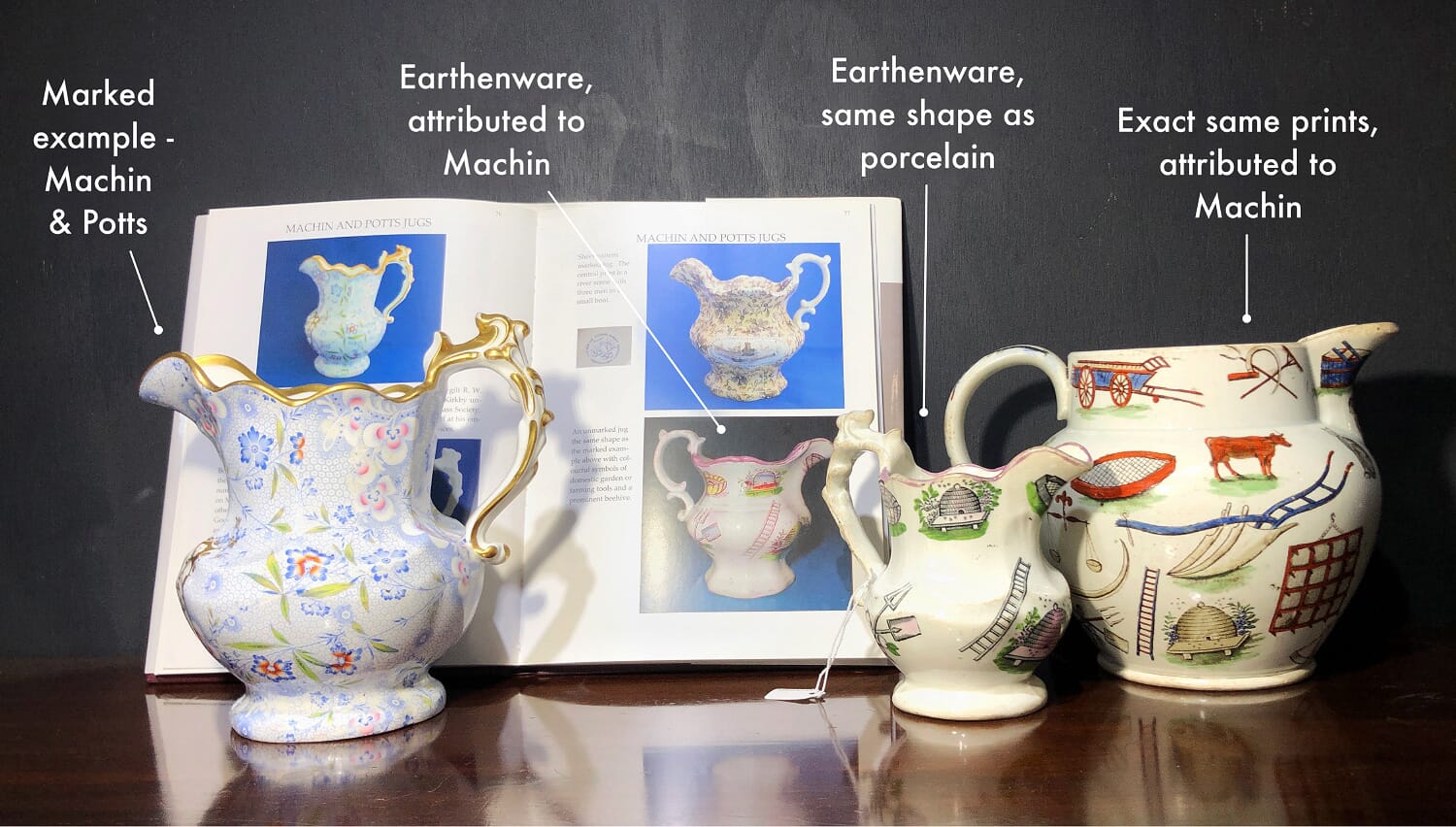

Did you know the ‘Father of Federation’ spent a lot of his time retailing ‘fancy goods’ in Sydney? His adverts make fascinating reading, giving a glimpse into the parlours and nurseries of Sydney in the mid-19th century.

Here’s a sample – from the stock of Moorabool Antiques, 170 years later! His shop must have been a present-day Antique Collector’s Aladdin’s Cave….

Adverts for Parkes, 1840’s-50’s

Sir Henry Parkes would have felt quite at home at Moorabool Antiques…. he was a business man and craftsman, learning the trade of ivory-turning before migrating to Australia in 1839. He opened a shop in Hunter Street, Sydney, where he sold ivory products he made, as well as a broad range of imported decorative & useful items:

“Bohemian Glass, Vases of rich and various patterns, handsome China ornaments, PORCELAIN FIGURES From one inch stature, and comprising a hundred varieties. Also, FIGURES IN BISCUIT CHINA. Children’s China, dinner, dessert, tea, and coffee Services. CHINA PUNCH BOWLS, Vases, flower-pots, pomatum jars, match cups, mugs, cream ewers, plates, teapots, etc. ROSEWOOD DRESSING CASES, work-boxes, fancy baskets, FANCY SMALL WARES: TORTOlSESHELL, enammelled and fine leather ladies’ companions, alabaster and enamelled jewel boxes, tortoiseshell and sandlewood card caes, fine leather and enamelled netting boxes, alabaster and silk paper weights, enamelled letter cases and toilet stands, tortoiseshell and leather cigar cases…….”

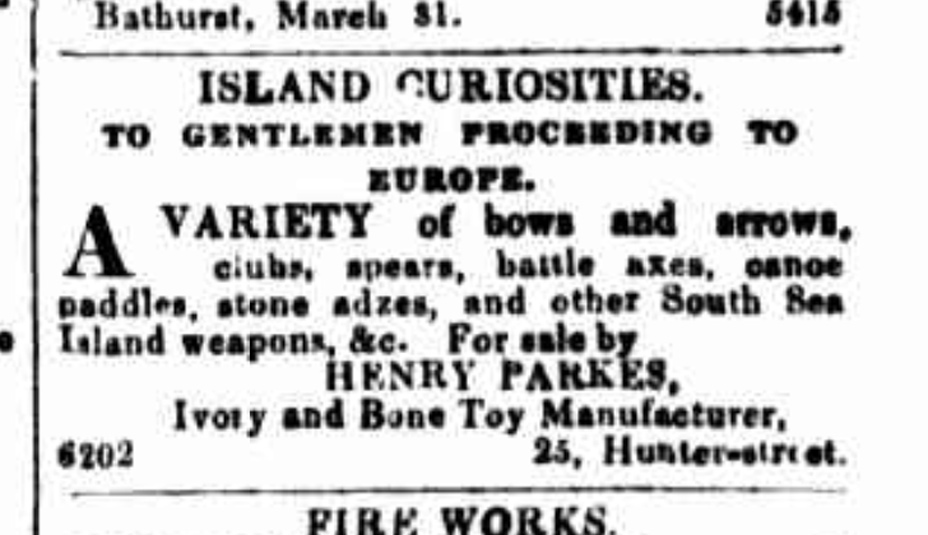

Another advert from 1846 is fascinating, as it is solely advertising Pacific Tribal Artifacts:

“ISLAND CURIOSITIES – To Gentlemen proceeding to Europe – A variety of bows and arrows, clubs, spears, battle axes, canoe paddles, stone adzes and other South Sea Island weapons &ect.”

Sounds familiar…. you’ll find exactly the same at Moorabool Antiques today – but now they’re Antique!

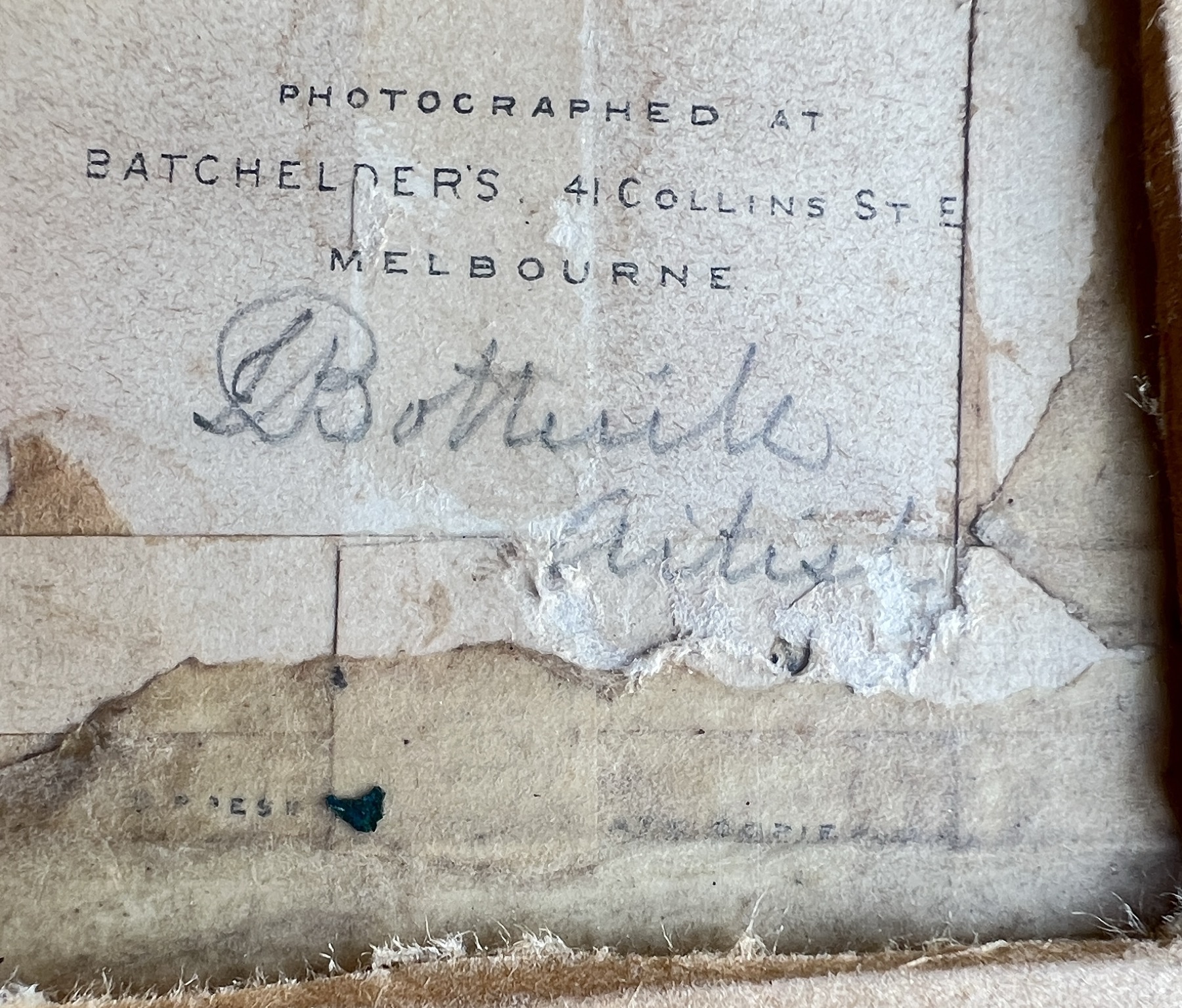

The second ‘Parkes’ item is a very personal portrait miniature. Purchased in original frame and untitled, an investigation of the backing discovered two inscriptions: firstly, it is a hand-coloured photographic portrait, with a printed back stating it is ‘Photographed at Bachelder’s, 41 Collins Street E, Melbourne’.

Second, it has an inscription declaring it depicts ‘Lady Parkes as Young Girl’.

It suddenly becomes an important part of the story of Australia.

The frame and mount are original, with the backing paper replaced with opening to show back of photo.

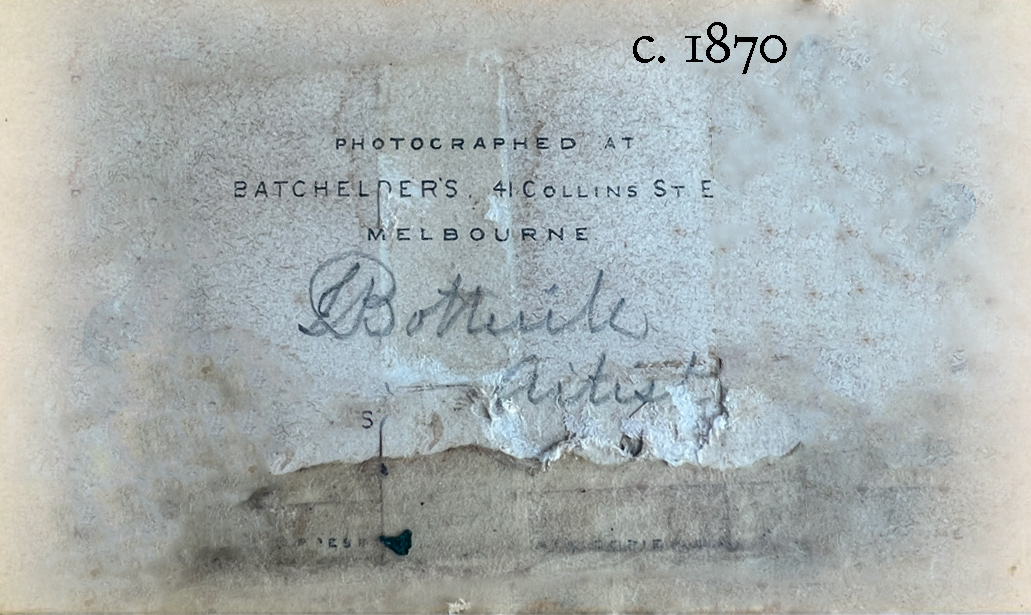

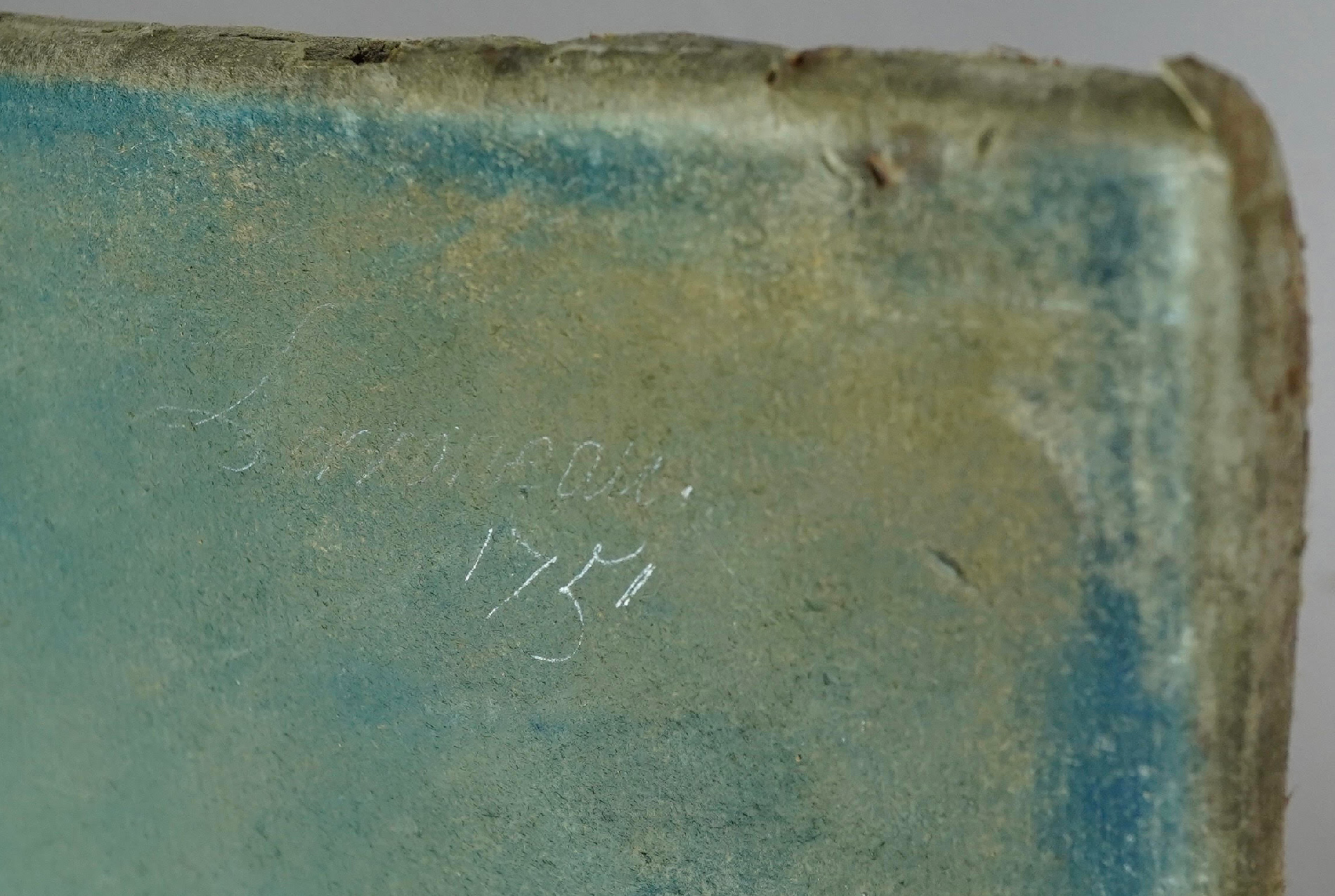

The inscription on the back reads ‘PHOTOGRAPHED AT BATCHELDER’S 41 COLLINS ST E., MELBOURNE’, over which is inscribed in pencil ‘Botterill / Artist’.

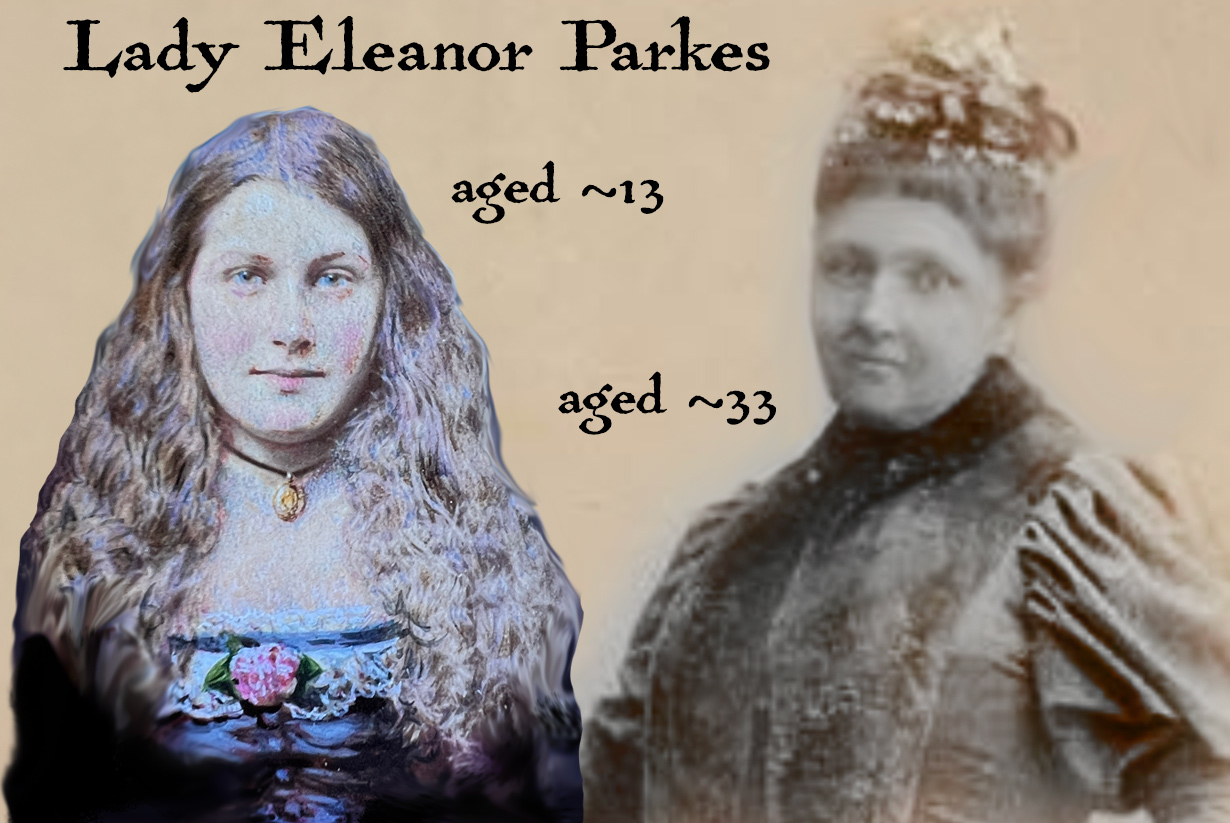

The three ‘Lady Parkes’

Who was the subject?

Lady Clarinda 1813-1888

There were three ‘Lady Parkes’, as Sir Henry always seems to have needed a companion – especially in his old age, where he had terrible luck with his partners.

His first wife, Lady Clarinda Parkes, was a Birmingham Dressmaker & Sunday-School teacher who married 21-year old Henry Parkes in Birmingham in 1836, when he was just ‘Mr Parkes’, son of a farmer and a novice businessman (which didn’t prosper for him). She came out to Australia with him, having their first child just 2 days before they landed, the first of 12. She had little public interaction, even when he became a notable in New South Wales government. She died in Sydney in 1888, aged 75 – and as this image we are considering is of a young ‘Mrs Parkes’, and is taken by a Melbourne photographer, it cannot be Clarinda who is depicted. She had 12 children, 6 of whom were still alive in 1888.

Lady Eleanor 1857-1895

The second ‘Lady Parkes’ was Lady Eleanor Parkes, a Sydney resident who married Sir Henry a few months after his first wife had died, in 1889. She took a keen interest in Politics, particularly social matters such as the plight of the ‘waifs’, the homeless youth of the time. She travelled with her husband as his political position grew, and appears to have been actively interested and supportive of his policies. She died from cancer in 1895, and they had five children.

Lady Julia 1872-1919

The third ‘Lady Parkes’ was Lady Julia Parkes, an Irish migrant born in 1872, employed as Nanny & House-keeper in the Parkes household, where she nursed the weakening Lady Eleanor. She married the 79 year old Sir Henry in 1895 – just months after the death of Eleanor. This was the shortest marriage, as Sir Henry died just 6 months later, in April 1896.

Setting out the three ‘Lady Parkes’ as above makes him look awfully unlucky – and afraid of being lonely….

But unlike Henry VIII, he wasn’t desperately seeking an heir – he’d already fathered a dozen children. Rather, he sought someone of the opposite sex to make his home ‘homely’, a companion for his old age and protector of his children.

So which of the three is the portrait at Moorabool?

Clarinda, the first Mrs Parkes, who married him when he was just a lad of 21, was apparently the love-of-his-life for the next five decades – but it was only months after she died (after a long illness) that Eleanor was married to Henry. As a contemporary commentator said in the papers, ‘…the community was startled by a report which was published, that Sir HENRY PARKES had just been married”…. The shock wasn’t just that ‘….she is considerably younger than her husband’ – 32, when he was 74 – but also the fact they had been an item while his elderly wife was ailing, and in fact already had two children together! So the untold story was that Sir Henry Parkes had married his mistress after his wife had died. His political opponents and the papers made the most of the situation….

This relationship was contentious – his daughters were reported to have left the house in disgust, his servants all quit before he returned with his bride, and the doors of Parliament were closed to him due to his ‘indiscretion’.

It was justified in the press:

The facts of the matter are, we learn, that the aged statesman, feeling the loneliness of his life when State cares, gave him a brief respite, determined some short time ago—for he is not a man to dilly-dally in such an important matter—that his final days should be soothed and made happy by a second partner of his joys and sorrows. …..

However, the plan of being soothed by Eleanor came crashing down when she became ill and soon died, in 1895.

Sir Henry Parkes continued his career of scandal by marrying his housekeeper, Julia, only three months after Eleanor passed away! Julia was an Irish migrant, and had been employed as the housekeeper / nanny in the Parkes household. She nursed the ailing Lady Eleanor, and it is said that Eleanor herself requested that Julia marry the elderly Sir Henry Parkes. Although somewhat scandalous, this made sense in the Victorian world: there were five young children in the household, and Henry had died penniless and in debt. Julia fulfilled his wish – she dedicated the rest of her life to this step-family, never re-marrying and going to great lengths to provide them with a stable upbringing. She was a remarkable woman.

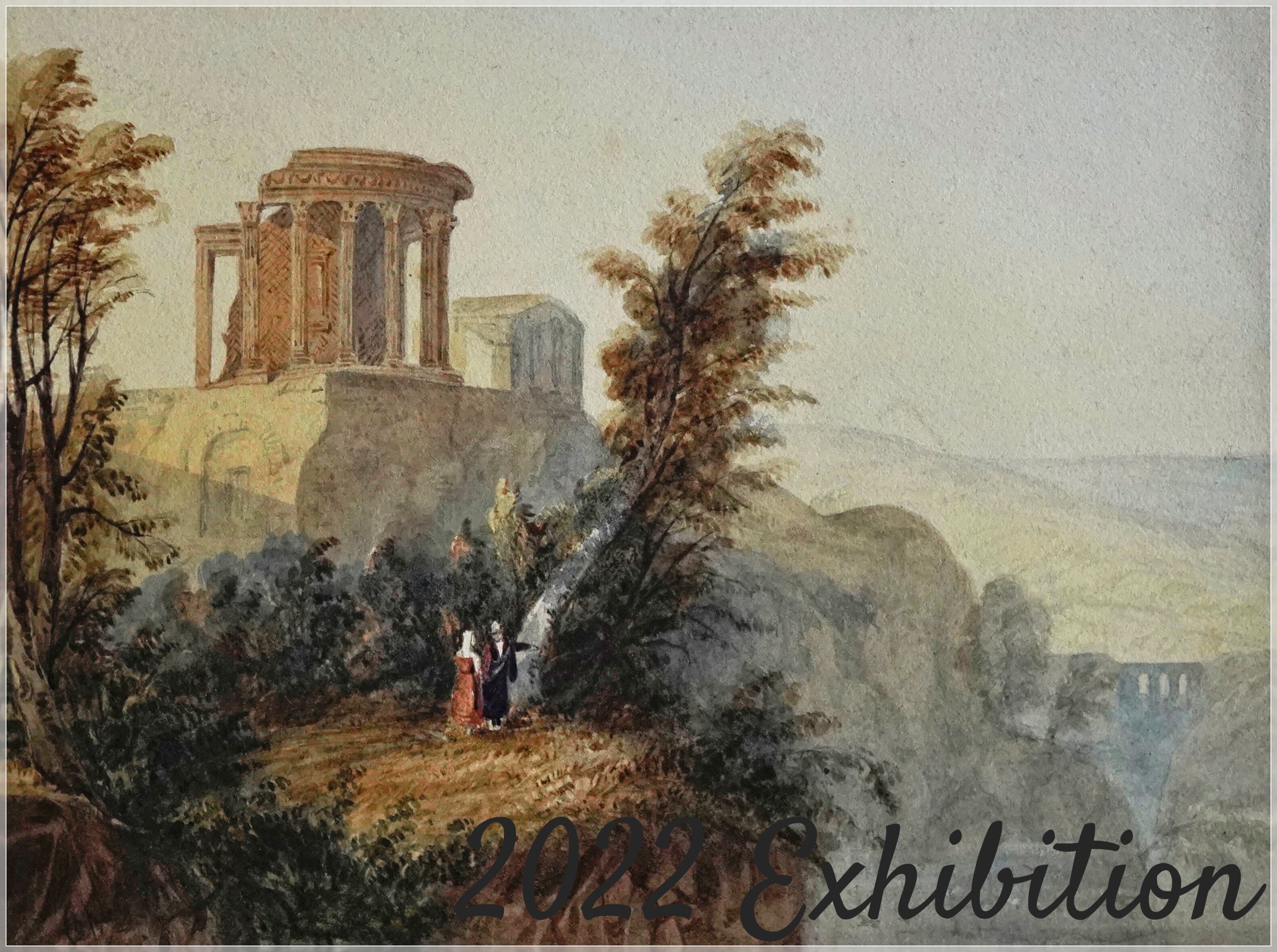

The Image: both a Photograph and a hand-painted Miniature.

This very engaging image is actually an albumen silver carte-de-visite, the traditional way of providing images for family & friends; however, while most would be placed into specially made albums with spaces the exact size of the image, this example is intact in it’s original Victorian frame, and behind glass. This is essential, as the fine painted surface, applied over the photographic image, is very vulnerable. The effect is superb, to the degree that when this was sold as a portrait of an unknown girl, it was also described as a ‘portrait miniature’ rather than a hand-coloured photograph.

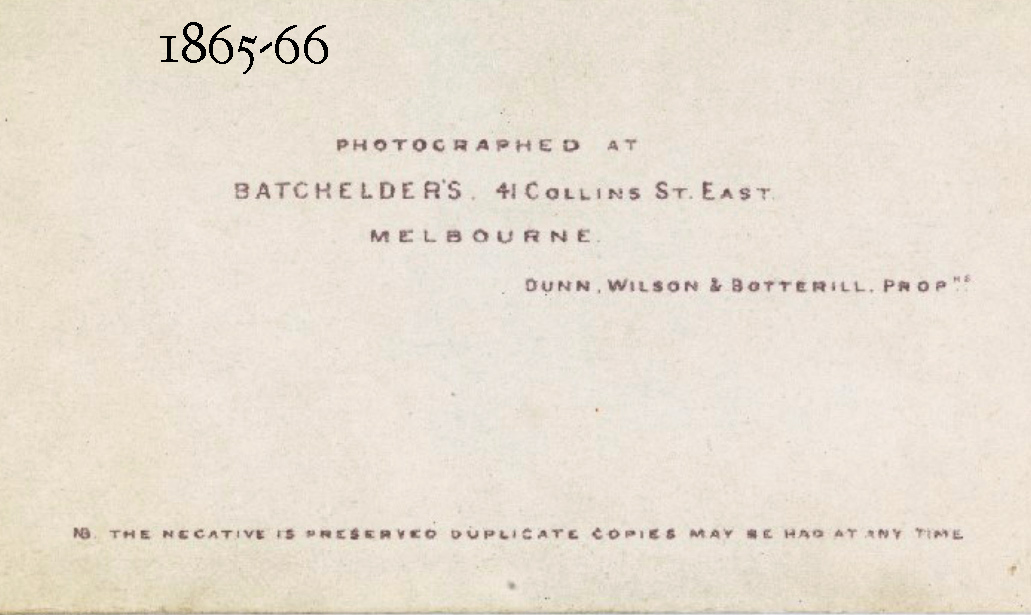

The work is produced in the Batchelder studio, 41 Collins Street East, Melbourne. This was established by the well-known American Batchelder brothers, who had come to the Australian goldfields directly from the Californian goldfields with the sole purpose of setting up a photographic business. While they had left by the stage this photo was taken, the studio name remained associated with the address for several decades.

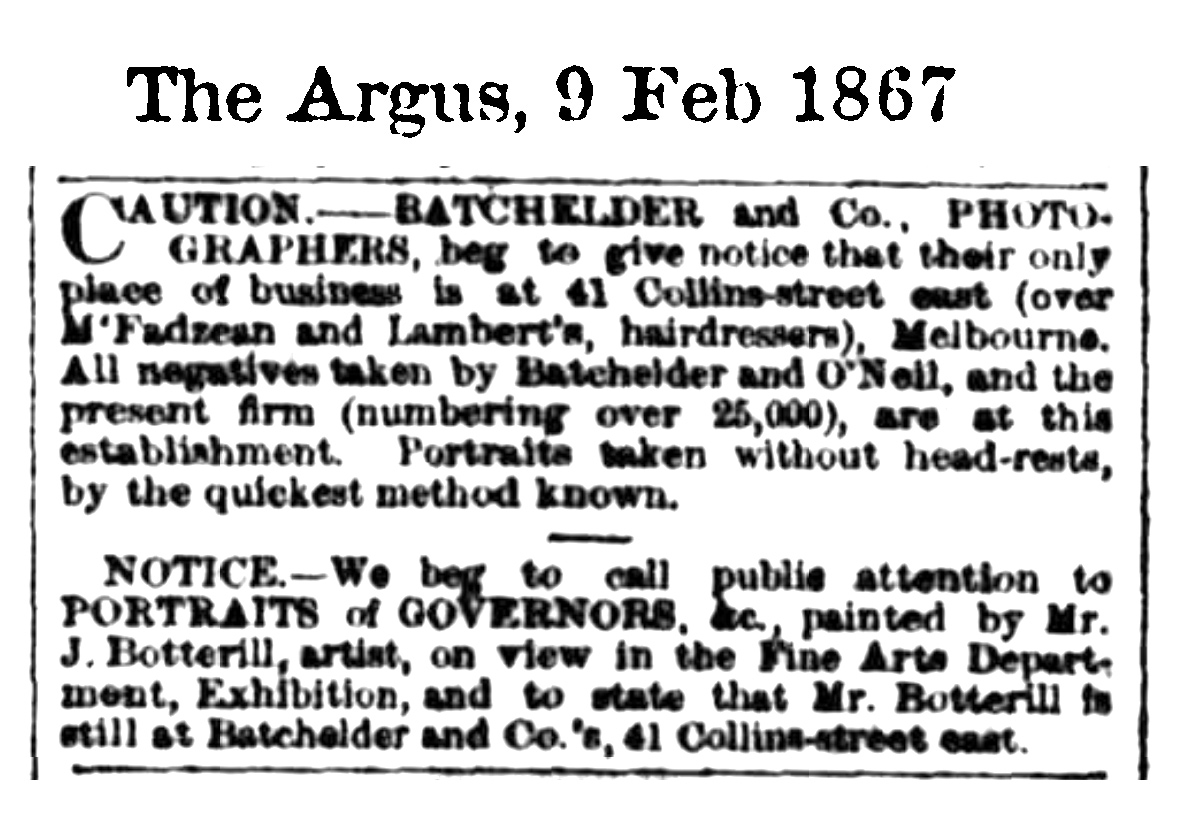

Batchelder’s was regarded as a premium establishment, and many of the images of notable members of Melbourne society of the period were the product of the studio. In 1867, an advert reminds the public that Batchelder’s has now been going for 11 years – ie since 1856 – and has stored over 25,000 negatives in case you would like a re-print!

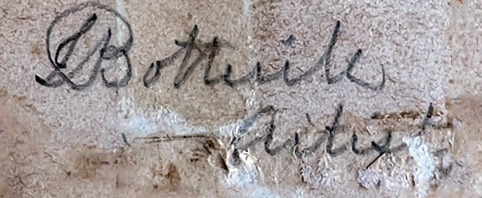

The image is signed in pencil to the back, ‘Botterill / Artist’. This is a very interesting detail: the ‘artist’ was John Botterill, described as miniaturist, portrait painter and professional photographer. He was active in Melbourne in the mid 1850’s joined the organising committee for the 1853 Victorian Fine Arts Society’s exhibition, to which he contributed eight works including a miniature self-portrait. In 1859, he is working as a ‘visiting master’ at Woodford House, a school for Young Ladies in Park Street. In 1861, he joined Batchelder’s Photographic Portrait Rooms in Collins Street East, ‘engaged … to paint miniatures and portraits in oil, watercolour or mezzotint – these deserve what they are receiving, a wide reputation’. He also gained knowledge of photography from somewhere, so probably learnt ‘on the job’ in the busy studio. In 1866, he became one of the partners of the firm alongside Dunn & Wilson, and in 1867 the firm won a medal at the Intercolonial Exhibition for their tinted photographs. This was the work of Botterill, as the advertising from that year emphasises:

“…the PORTRAITS… painted by Mr J. Botterill, artist…. on view in the Fine Art Department , (at the) Exhibition, and to state that Mr Botterill is still at Batchelder and Co’s, 41 Collins St East..”

The use of ‘is still at‘ is curious, and perhaps reveals problems in the company. They parted ways at around this time. In his 1869 adverts, Botterill declares:

“J. BOTTERILL. Portrait

Painter and Photographer, REMOVED from

Batchelder’s to 19 Collins Street East”

He continues at this address for several years, before opening in Elizabeth Street for his final years. He died in 1881.

Who is ‘Lady Parkes’?

The subject of this photo would be hard to place if it didn’t have the inscription, added to the backing of the original. Sir William Parkes had 3 wives, but we can identify who this one is by the fact the photography studio was in Melbourne. His first, Clarinda, was born in England in 1813 and far too old when they migrated to Sydney in 1839. The third, Julia was born in 1872 – probably after this photo was taken – so she’s not possible. The second, Eleanor, was born in 1857, so is the right age for a Melbourne photograph in the late 1860’s, early 70’s.

John Botterill signed this piece, on a Batchelder-branded photograph. Note there is no ‘partnership’ described, as was the case 1866-68. Having the partnership details removed would suggest it belongs to a transitional period – the photograph taken at 41 Collins Street East, with the painting done by Botterill a few doors down at his studio, 19 Collins Street East. There was still a strong connection, as after Botterill died in 1881, the Batchelder studio advertises that they have added the archive of Botterill’s negatives to their own extensive archive.

The final dating evidence is the arrival of Eleanor Dixon, the future Lady Parkes, in Melbourne as a migrant. She was from Wooler, Northumberland, one of five children, her father listed as a ‘Master Shoemaker’. He died in 1869, and several months later, Eleanor’s elder brother was married and promptly left for Australia. Eleanor and three siblings followed in 1870, accompanied by their mother.

1870 becomes the most probable date for the portrait. Eleanor would have been 12 or 13, an appropriate age for the girl in the photo, who still has her hair ‘out’, indicating she was not yet considered an adult. Around her neck is a black ribbon with large gold locket: this is typical Victorian mourning jewellery, and no doubt had a portrait of her late father in it.

We can imagine the scene: the newly arrived family caught up in the bustle & thrill of Marvellous Melbourne in the post-Gold rush boomtown, celebrating their new life with a very fine portrait. She engages the viewer with a very frank, inquisitive look. There’s a pink rose on her dress, and she is presented as a true ‘English Rose’, her hair spilling wildly out over her lace-trimmed dress, not yet constrained on top of the head in an adult style. For the young Eleanor, the future was as golden as the mounts of this image; anything was possible – and indeed, for a few years in the 1890’s she achieved something remarkable, marrying one of the most powerful men of the age, the ‘Father of Federation’.

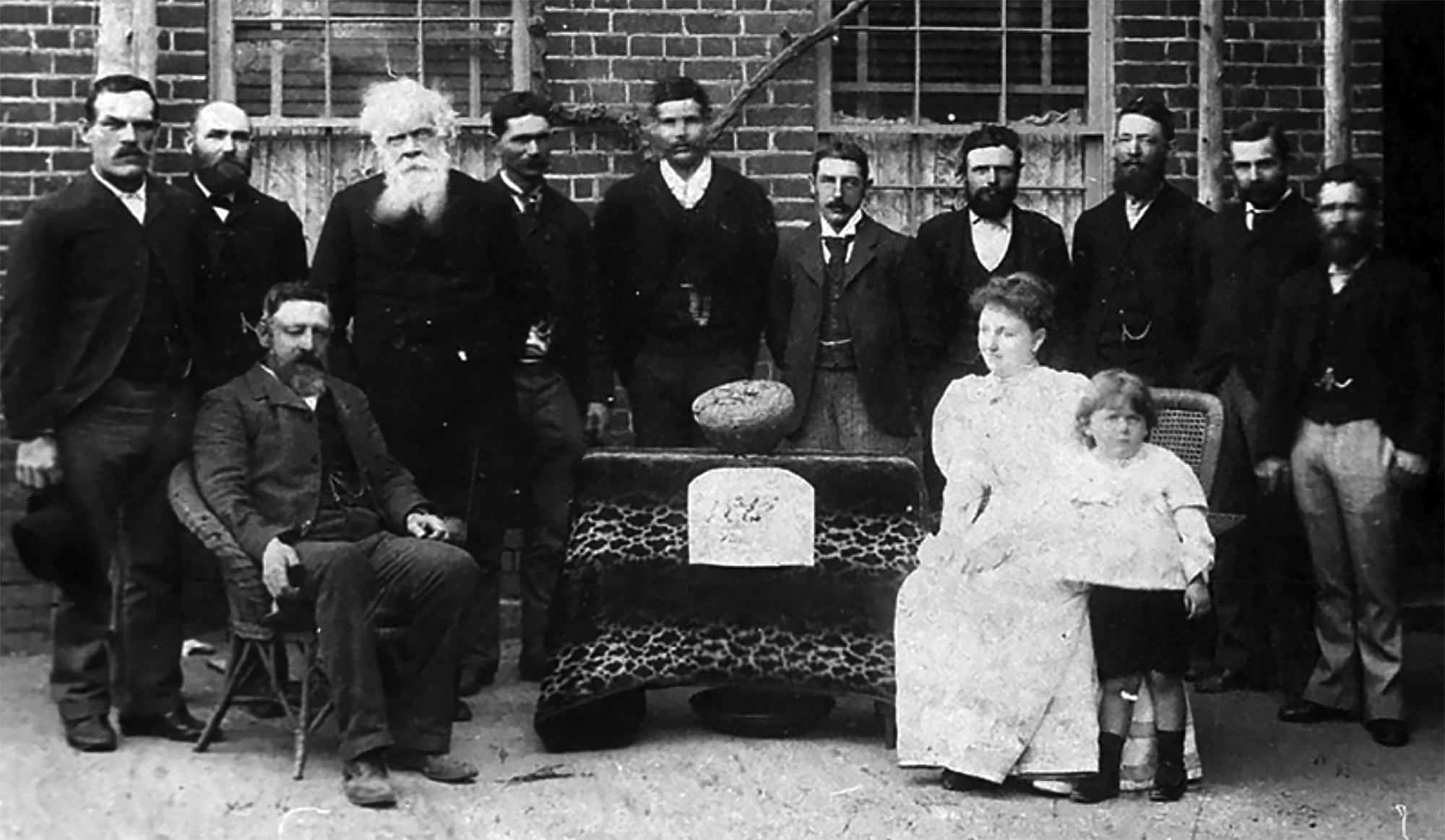

On the theme of a ‘Golden Future’, there’s a wonderful image of Lady Eleanor Parkes on tour with Sir Henry: they were visiting the offices of Bushman’s Mine in around 1890; sitting to the right with her son is Eleanor, beside a very strong table on which sits a big lump of gold castings. The label at the front reveals its weight to be 1,347oz – and named “The Lady Parkes” in her honour!

©Paul Rosenberg, Moorabool Antiques, Geelong. Please contact if you wish to reproduce any part of this documentation. Images from various online sources, mostly TROVE-accessed archives.

Further Info on John Botterill & the Batchelder & Co Studio.

Then comes the ‘big one’ –

Then comes the ‘big one’ –