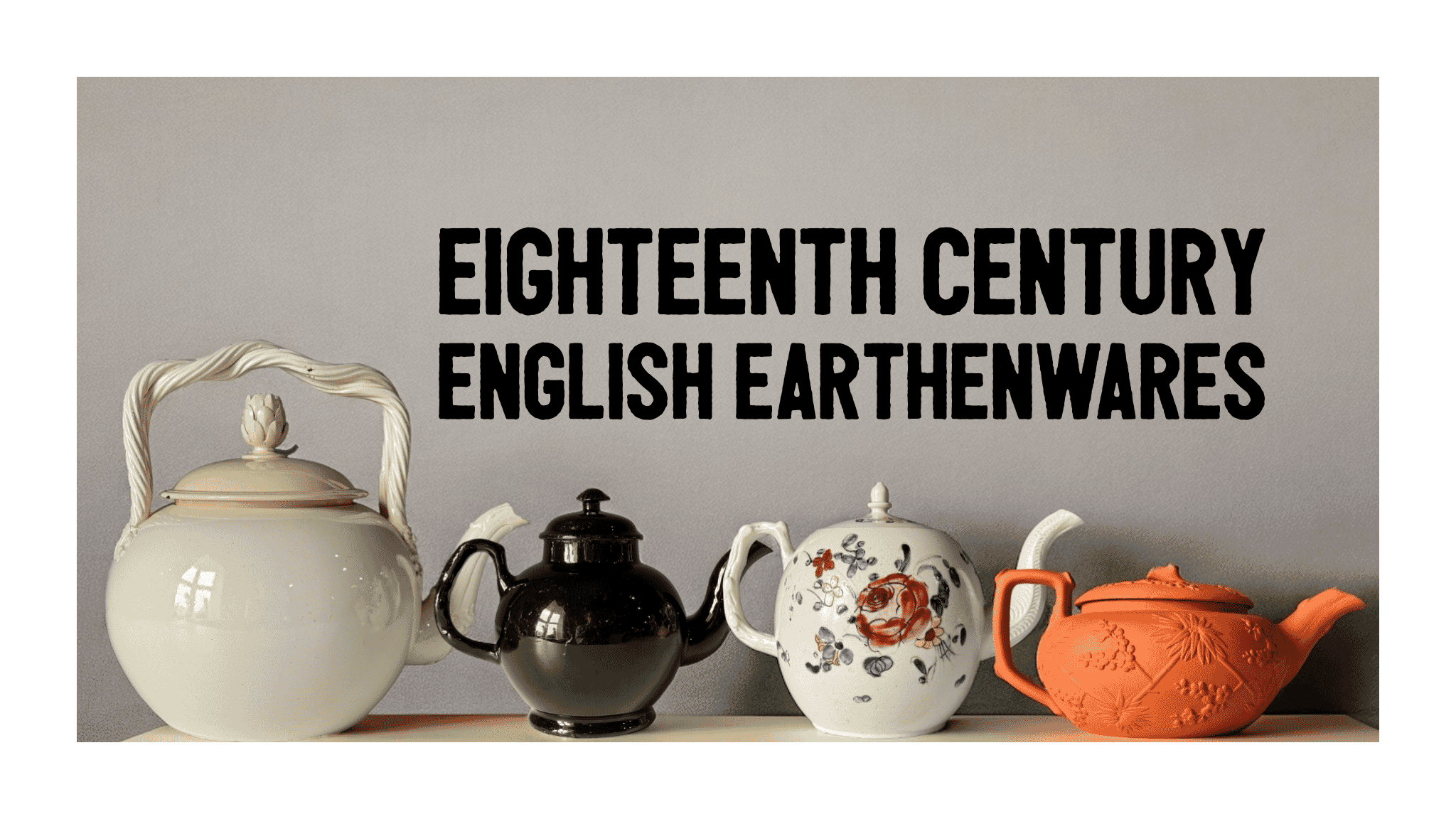

Creamware

Creamware is the term for an English earthenware body with a definite ‘cream’ tone, popular in the latter half of the 18th century and replicated across Europe. It emerged from the experimentation of Staffordshire potters seeking a local alternative to expensive Chinese porcelain around 1750. Their innovation yielded a refined cream to white earthenware with a lustrous clear lead glaze, prized for its lightweight construction and pristine finish, making it ideal for household use.

It was not expensive to produce when compared with porcelain, but also not as robust; replacements were probably a necessity if you were using Creamware tea wares or tablewares. After its heyday in the 1780’s, Creamware remained popular well into the 20th century despite competition from other ceramic types. Today, it is valued for the pleasant off-white body and refined shapes often decorated with bright spontaneous on glaze enamel flowers.

-

Creamware punch pot / tea kettle with baroque face & double strap handle, English c. 1780$840.00 AUD

Creamware punch pot / tea kettle with baroque face & double strap handle, English c. 1780$840.00 AUD -

Creamware tea canister, engine turned with flower swags, c. 1790$480.00 AUD

Creamware tea canister, engine turned with flower swags, c. 1790$480.00 AUD -

Creamware Coffeepot, Rhodes type flowers, c. 1770$425.00 AUD

Creamware Coffeepot, Rhodes type flowers, c. 1770$425.00 AUD -

Rare creamware tankard, C. 1780$595.00 AUD

Rare creamware tankard, C. 1780$595.00 AUD -

Hartley Green & Co, Leeds, creamware plate, flower dec. c.1810$225.00 AUD

Hartley Green & Co, Leeds, creamware plate, flower dec. c.1810$225.00 AUD

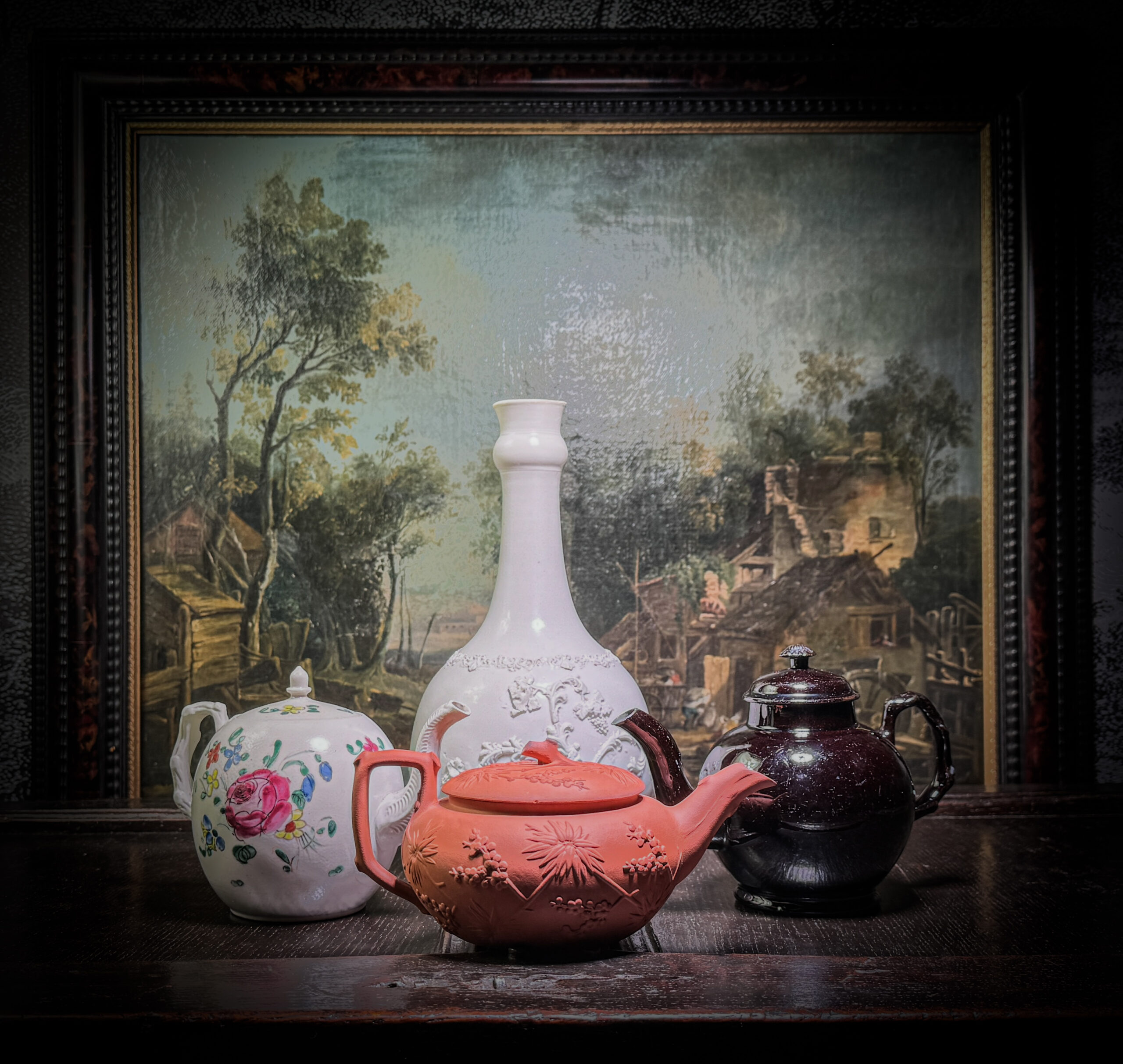

Salt glaze

Salt glaze refers to a distinctive ceramic made by the English potters in the mid-18th century, with an ivory-white stoneware body lightly glazed with a clear covering having a texture resembling orange peel.

This forms on the white high-fired stoneware body when common salt is introduced into the kiln at its highest temperature. During firing, sodium from the salt reacts with silica present in the clay, resulting in the formation of a glassy sodium-silicate coating. This glaze can exhibit a range of slight hues, usually colourless but also found in shades of brown (due to iron oxide), blue (from cobalt oxide), or purple (from manganese oxide).

The result is a glistening white product, usually slip-cast and very lightweight & thin, yet also very tough. Forgive me for making the comparison, but it could be mistaken for a plastic! The glaze is transparent, and fits tight and thin against the body, meaning any moulded decoration is as sharp and crisp as the clay beneath. It has become a highly desireable field to collect in the English Earthenwares field.

-

Saltglaze guglet with rococo scroll & fruiting vine sprigging, c. 1750$1,250.00 AUD

Saltglaze guglet with rococo scroll & fruiting vine sprigging, c. 1750$1,250.00 AUD -

Saltglaze Teapot with bright flower decoration, c. 1760$675.00 AUD

Saltglaze Teapot with bright flower decoration, c. 1760$675.00 AUD -

Wedgwood smearglaze teapot, wheat sheaf knop & basketweave, c. 1820$495.00 AUD

Wedgwood smearglaze teapot, wheat sheaf knop & basketweave, c. 1820$495.00 AUD -

English saltglaze ‘House’ teapot, British coat-of-arms, c. 1745$1,250.00 AUD

English saltglaze ‘House’ teapot, British coat-of-arms, c. 1745$1,250.00 AUD -

Saltglaze -Flora- wall pocket, circa 1770Sold

Saltglaze -Flora- wall pocket, circa 1770Sold -

Saltglaze ‘bamboo’ teapot, pale teal colour, c. 1790$580.00 AUD

Saltglaze ‘bamboo’ teapot, pale teal colour, c. 1790$580.00 AUD -

Saltglaze Flora cornucopia, Wedgwood/Greatbatch type, c.1765$1,850.00 AUD

Saltglaze Flora cornucopia, Wedgwood/Greatbatch type, c.1765$1,850.00 AUD

Redware

The Chinese were fond of a red clay sourced near the city of Yi Xing, on the Yangtze River Delta. When Europeans started trading with them in the 17th century, the ‘Yixing Stonewares’ were a popular item. Naturally, the local European potters were keen to provide versions of this suddenly popular ware, and the potters of Delft, in Holland produced a ‘clone’ of the Chinese – often with the same decoration – in the latter 17th century, followed by the Eeler Brothers, Dutch silversmiths who came to London in the 1680’s and produced the first English redwares. Meissen was a latecomer, with J.J.Böttger discovering a fine high-fired red ware body now named after him in 1706. By the mid 18th century, the potters of Staffordshire and elsewhere were making Redwares.

Characterized by its rich reddish-brown hues derived from iron in the clay oxidising in the firing process, English Redware exemplified both utilitarian functionality and aesthetic charm. Crafted with meticulous attention to detail, these pieces often featured simple yet elegant designs, at first copying the imported Chinese wares, but soon reflecting the prevailing tastes of the era. Commonly used for everyday household items such as teapots, jugs, and mugs, English redware found its place in both rural cottages and aristocratic homes alike. Despite its widespread popularity, redware production faced challenges from the emerging dominance of porcelain and other fine ceramics. Wedgwood brought it back to the tasteful table in the late 18th- early 19th century with a refined version they called ‘Rosso Antico’, and other firms through the Victorian era continued to make ‘redwares’ in small numbers. The original 18th-century English redware remains a testament to the skilled craftsmanship and enduring legacy of the era’s pottery traditions.

Jackfield

Jackfield is largely a generic name for a class of black/brown bodied earthenwares with a glossy ‘black’ glaze. I emphasise ‘black’ as close examination reveals it is actually made up of mostly dark brown tones, which combined with a dark-toned clay body appears black to the naked eye.

Traditionally this type of ware was said to be made at a pottery works located at Jackfield, near Coalport in Shropshire – which became the name for the type. But excavations and other evidence suggest that at the same time, such pieces were also made in Staffordshire and at other ceramic centres. The shapes and mouldings are often closely related to the other bodies detailed in this article, showing the black products were made alongside red wares , cream wares and salt glaze. Perhaps ‘black wares ‘ would be a more accurate name, but the ‘Jackfield’ name persists.

Decoration was hard, as the black surface didn’t allow for the usual decorative technique. Rare ‘cold-painted’ examples show that some were decorated in colourful oil paints, often with dedications and dates, painted onto a piece to order by a retailer, independent of the potteries.

Today, it is collected for the dramatic impact it makes in contrast to the usual white or off-white alternative wares.

-

Jackfield-type Teapot, deep brown glaze & crabstock handle, c. 1780$780.00 AUD

Jackfield-type Teapot, deep brown glaze & crabstock handle, c. 1780$780.00 AUD -

Jackfield glaze jug & cover, silver urn knop & animal head terminal, c. 1770$860.00 AUD

Jackfield glaze jug & cover, silver urn knop & animal head terminal, c. 1770$860.00 AUD -

Staffordshire pottery cow creamer, c.1870$240.00 AUD

Staffordshire pottery cow creamer, c.1870$240.00 AUD -

Product on sale

Jackfield glaze loving cup with ‘cold colour’ flowers, C. 1780Original price was: $480.00 AUD.$432.00 AUDCurrent price is: $432.00 AUD.

Jackfield glaze loving cup with ‘cold colour’ flowers, C. 1780Original price was: $480.00 AUD.$432.00 AUDCurrent price is: $432.00 AUD. -

Product on sale

Large Jackfield type baluster shape jug, C. 1765Original price was: $495.00 AUD.$445.50 AUDCurrent price is: $445.50 AUD.

Large Jackfield type baluster shape jug, C. 1765Original price was: $495.00 AUD.$445.50 AUDCurrent price is: $445.50 AUD. -

Jackfield glaze teapot, fruiting vine & flower knop, c. 1760$1,250.00 AUD

Jackfield glaze teapot, fruiting vine & flower knop, c. 1760$1,250.00 AUD