Bonjour…. in celebration of today’s French significance, we have a nice array of French items for you to browse, Fresh to Stock at Moorabool.

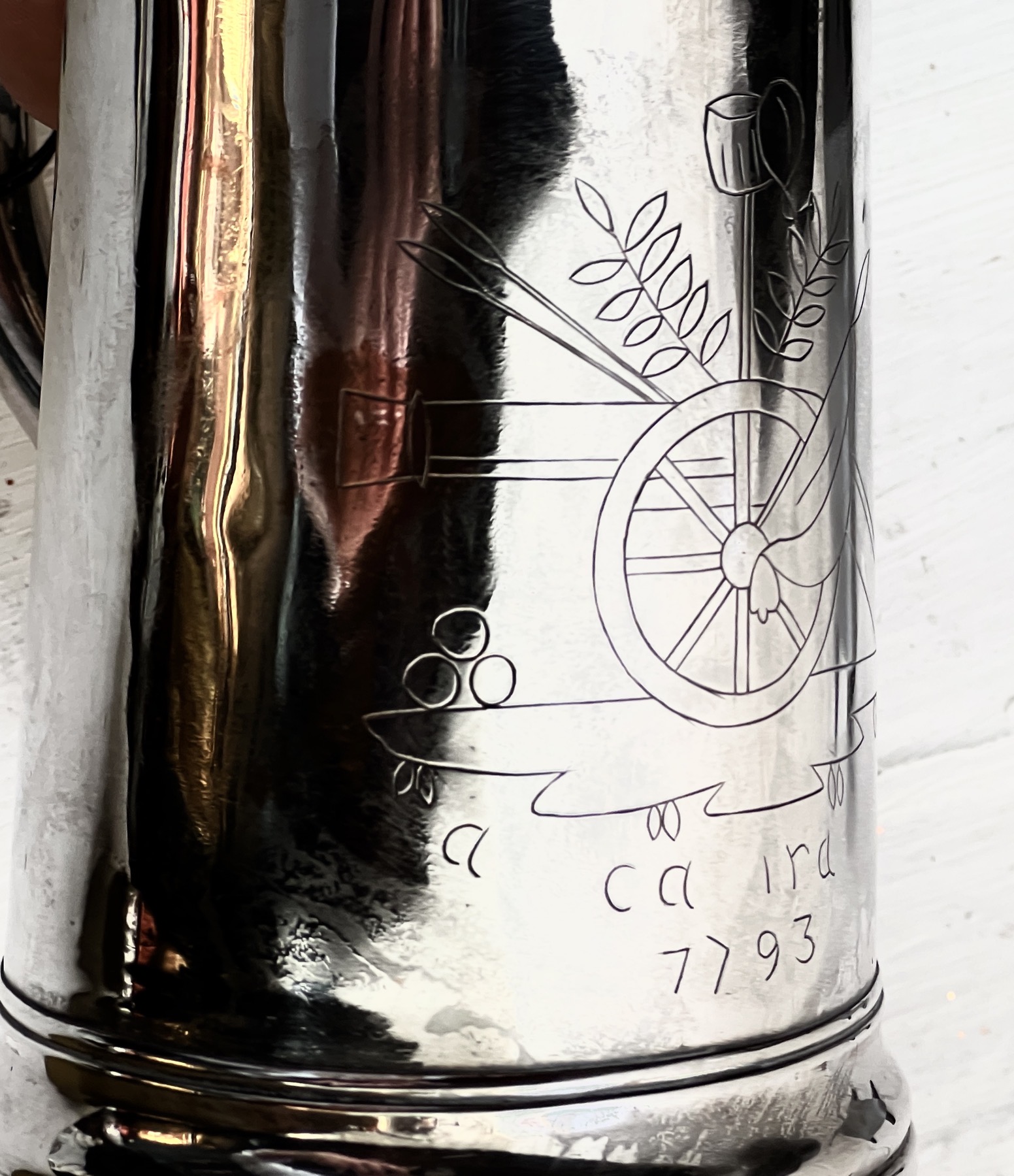

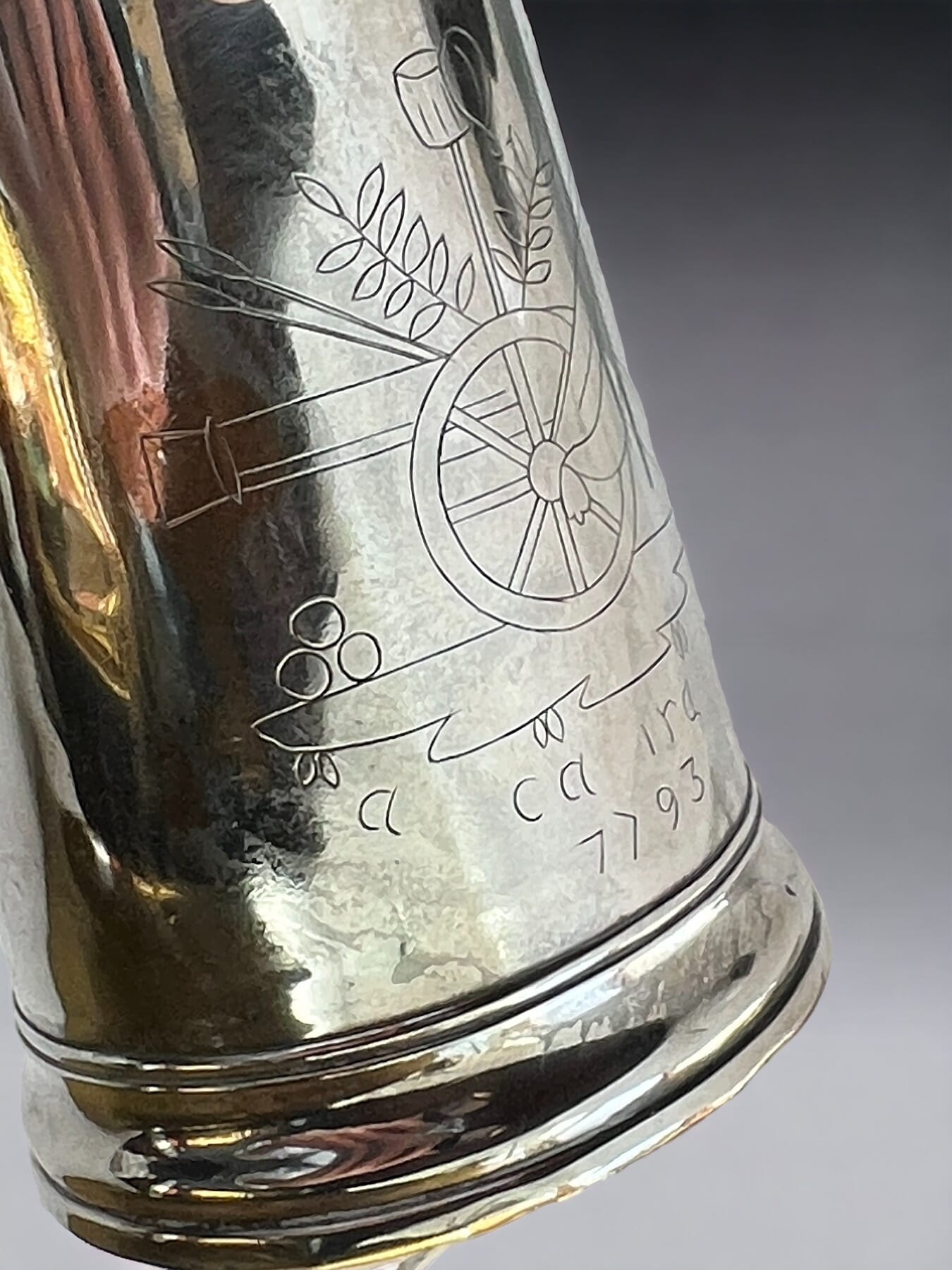

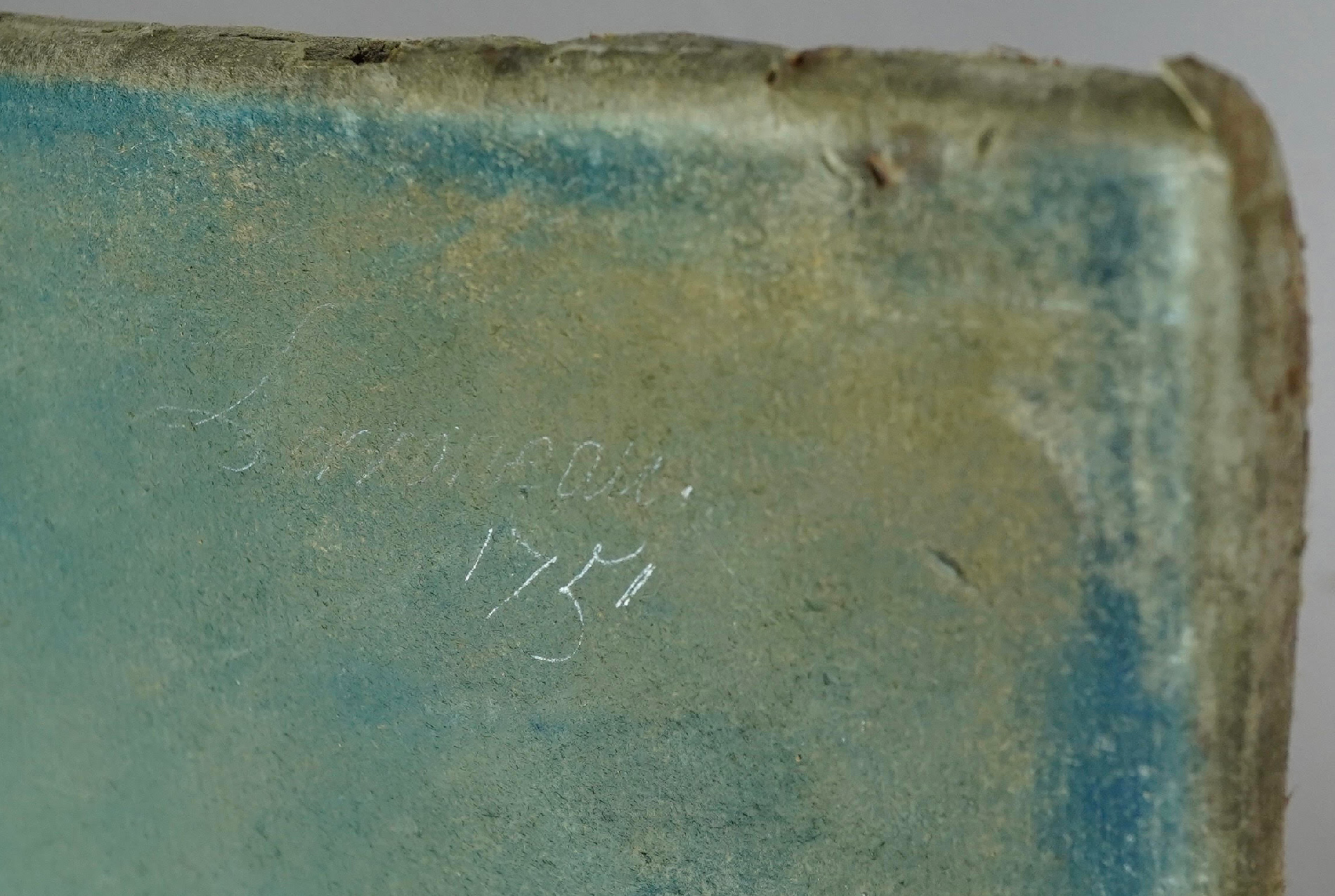

This interesting Revolutionary relic celebrates 1793: the year the Revolution ‘crossed the line’, executing the King & Queen, and purging the Ancien-Regime from France. The Cannon and cannonballs show the militant direction the revolution took, as 1793 was also the year France declared war on pretty well every European nation. Below is an inscription, ‘a ca ira’ – It’ll be OK, or as the Australian slang goes, ‘No worries!’

This is the chorus of a popular French song, ‘Ca Ira’. Ironically, the music is slightly older than the revolution, said to be a favourite of Marie Antoinette who would play it on her harpsichord. The words were put to it around 1790, and came to include a reference to Marie – calling her ‘the Austrian Slave’ ….

It was said to be the great Benjamin Franklin, while in France at the time as representative of the fledgling United States, who inspired the chorus. He had successfully led the revolution to free the people of America from tyranny – inspirational for the French seeking something similar. When asked for an opinion on France’s revolution, he would reply in broken French “Ça ira, ça ira” (“It’ll be fine, it’ll be fine”).

It was a ‘working song’ for the preparations for the first Fête de la Fédération, held on the 14th July 1790, being the one year anniversary of the storming of Bastille – and still celebrated 232 years later…..

‘Ca Ira’ is repeated after every verse: the verses were elaborated on and changed as the revolution progressed; an earlier version goes:

“An armed people will always take care of themselves.

We’ll know right from wrong,

The citizen will support the Good.Ah ! It’ll be fine, It’ll be fine, It’ll be fine

When the aristocrat shall protest,

The good citizen will laugh in his face,

Without troubling his soul,

And will always be the strongerAh! It’ll be fine, It’ll be fine, It’ll be fine…”

By the end of the revolution, as the blood of the nobles flowed, the words used were:

”aristocrats to the lamp-post

Ah! It’ll be fine, It’ll be fine, It’ll be fine

the aristocrats, we’ll hang them!If we don’t hang them

We’ll break them

If we don’t break them

We’ll burn them…..We shall have no more nobles nor priests

Ah! It’ll be fine, It’ll be fine, It’ll be fine

Equality will reign everywhere

The Austrian slave shall follow him

Ah! It’ll be fine, It’ll be fine, It’ll be fine

And their infernal clique

Shall go to hell

Ah! It’ll be fine, It’ll be fine, It’ll be fine….”

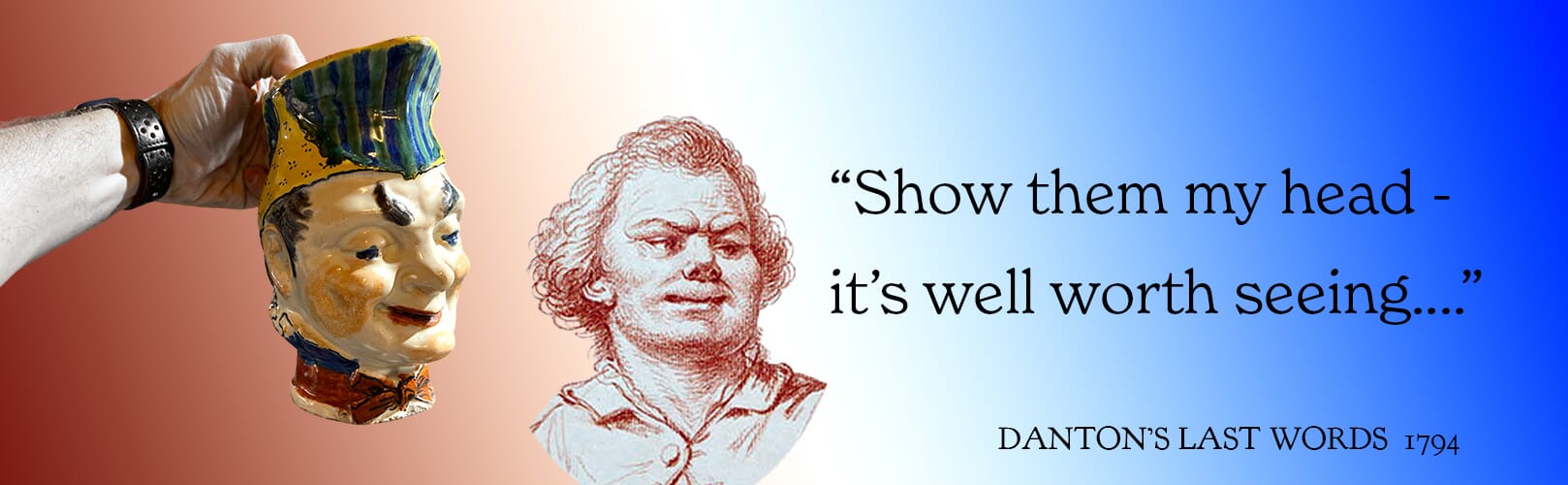

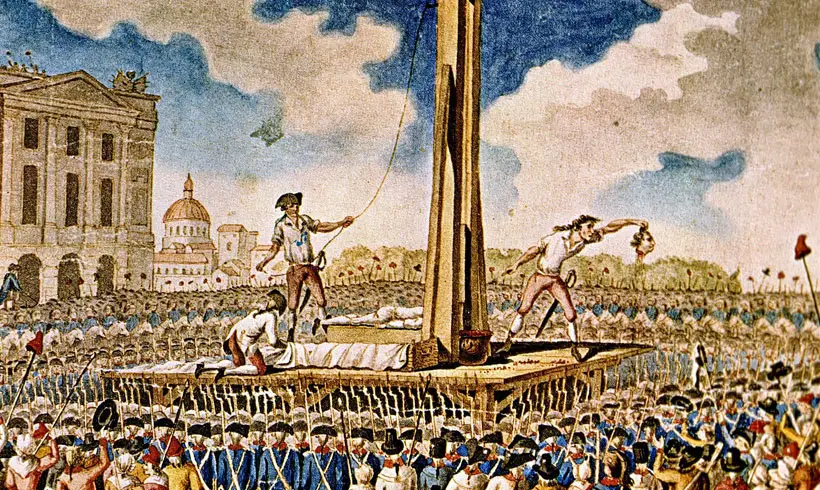

1793 was the year ‘The Terror’ began. After Louis XVI and Marie Antionette lost their heads, the purge of the ancien regiem gathered pace as more and more privileged aristocrats came under suspicion of not being loyal. Heading the purge was Georges Jacques Danton. As head of the ‘Committee of Public Safety’, he was able to remove all opposition, using that French favourite, the guillotine. Until one day, he himself met the same fate for not being radical enough! The ‘character jug’ below is French, of the Revolutionary period – and looks just like him. Read More to follow our attribution of this character to the feared Georges Danton.

Often mis-labelled a ‘Toby Jug’, this is an early version of a comical jug that becomes popular in the latter 19th century, sometimes identified as ‘Puck’. We believe this head jug is a distinctive character, and as it belongs to the period of the French Revolution, his identity must be found in that timespan. His appearance matches that of Georges Jacques Danton (17591794), an important public figure of the late 18th century in France, and the perfect candidate for a slightly humorous head mug like this.

The ‘French Room’ at Moorabool Antiques

In the upstairs centre of our Geelong premises we have constructed a ‘French Salon’. The walls are the basis, being a series of rare surviving early 19th century wallpaper panels. They were never used – they still have the trim marks along the edges, usually cut-off when installed.

The fabrics you see are all rather special – Aubusson weavings, including large floor carpet, wall panels, large & small upholstery panels, curtain pelmets, and even a pair of shield-shape fire screens…. all unused, purchased in France on the eve of WW1, shipped out, and left in the boxes until now. In other words, brand-new Antique fabrics, ready for the keenest of French decorators…. we’re hoping they will sell as a complete group, otherwise there will be a split-up into groups. Email if this sounds interesting.

There’s also a series of rather special French pieces, some already online, with more to be added shortly.

Note the portrait in the centre: this is signed & dated pastel, a portrait of Jeanne-Marie- Malles, aged 18, as ‘Dianna the Huntress’. It’s by the pastel master, Jean Baptiste Perronneau (1716-83), regarded by leading scholar in the field, Neil Jeffares, as one of the two ‘best pastel portraitists‘ of the 18th Century (alongside M. de La Tour 1704–1788).

See this exciting freshly identified piece here >

French Furniture

-

French Mahogany armchair with scroll arms, circa 1870Sold

French Mahogany armchair with scroll arms, circa 1870Sold -

French Mahogany open armchair with scroll arms, rosettes, c. 1870$540.00 AUD

French Mahogany open armchair with scroll arms, rosettes, c. 1870$540.00 AUD -

French Ebonized and amboyna venner work table with musical trophy and ormolu mounts, c. 1870$850.00 AUD

French Ebonized and amboyna venner work table with musical trophy and ormolu mounts, c. 1870$850.00 AUD -

Petite French Fauteuil, gold silk, Louis XV period c.1760$1,450.00 AUD

Petite French Fauteuil, gold silk, Louis XV period c.1760$1,450.00 AUD -

Louis XV style fauteuil, early 20th centurySold

Louis XV style fauteuil, early 20th centurySold -

Louis XV style fauteuil, early 20th centurySold

Louis XV style fauteuil, early 20th centurySold -

Pair of French Fauteuils, Louis XV period circa 1765$2,950.00 AUD

Pair of French Fauteuils, Louis XV period circa 1765$2,950.00 AUD -

Small French Provincial buffet, Louis XV period$2,950.00 AUD

Small French Provincial buffet, Louis XV period$2,950.00 AUD -

Large French Fauteuil, Louis XIV C.1700$2,450.00 AUD

Large French Fauteuil, Louis XIV C.1700$2,450.00 AUD -

Large French Fauteuil, scroll arms, Louis XIV, Circa 1700$2,450.00 AUD

Large French Fauteuil, scroll arms, Louis XIV, Circa 1700$2,450.00 AUD -

Large French Provincial amoire, Louis XIII, mid-17th century$5,800.00 AUD

Large French Provincial amoire, Louis XIII, mid-17th century$5,800.00 AUD -

Pair of Louis XVI style accent chairs as-is, c.1890$280.00 AUD

Pair of Louis XVI style accent chairs as-is, c.1890$280.00 AUD

There’s a strong French Connection with Australia: we could well have been a French colony…..

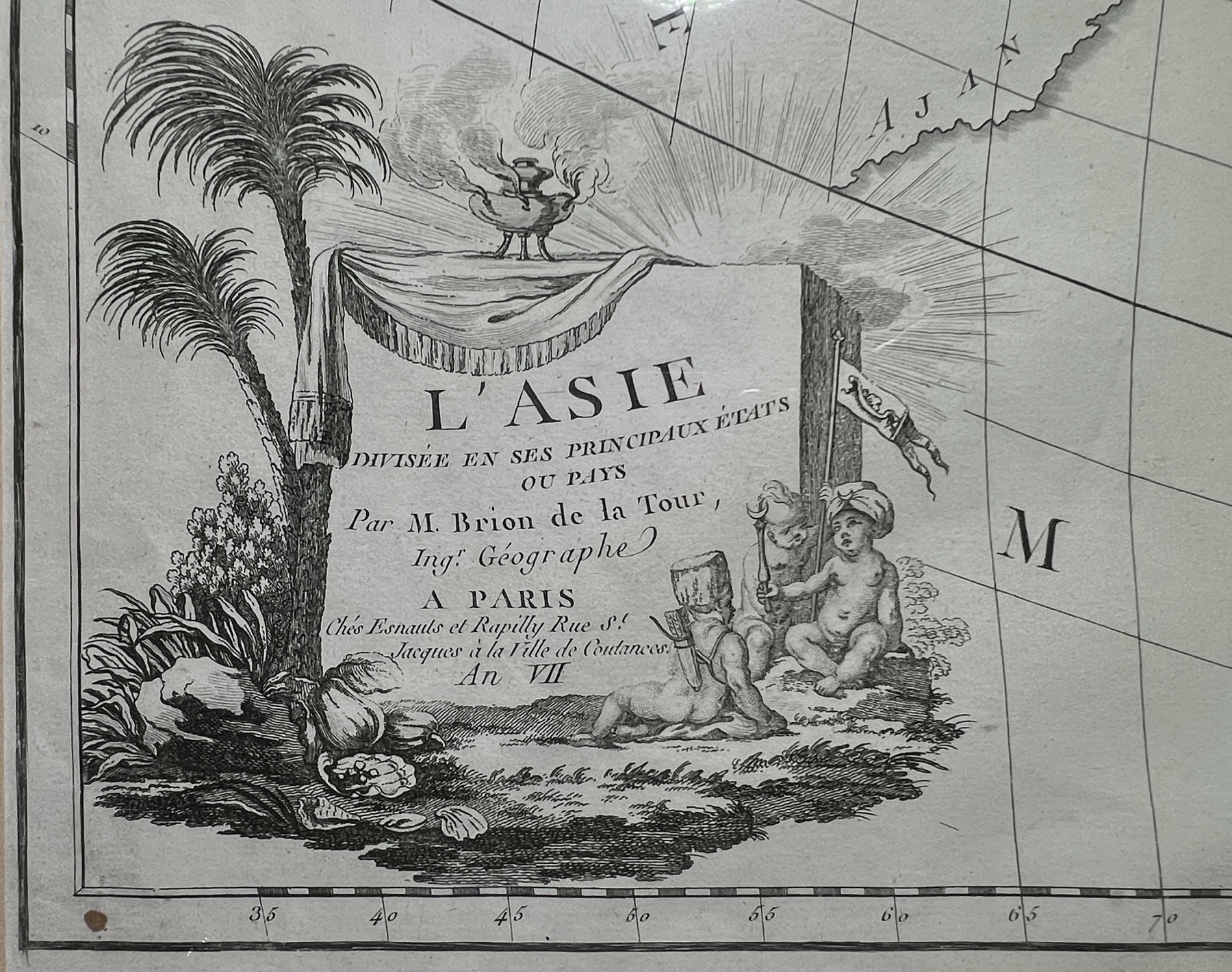

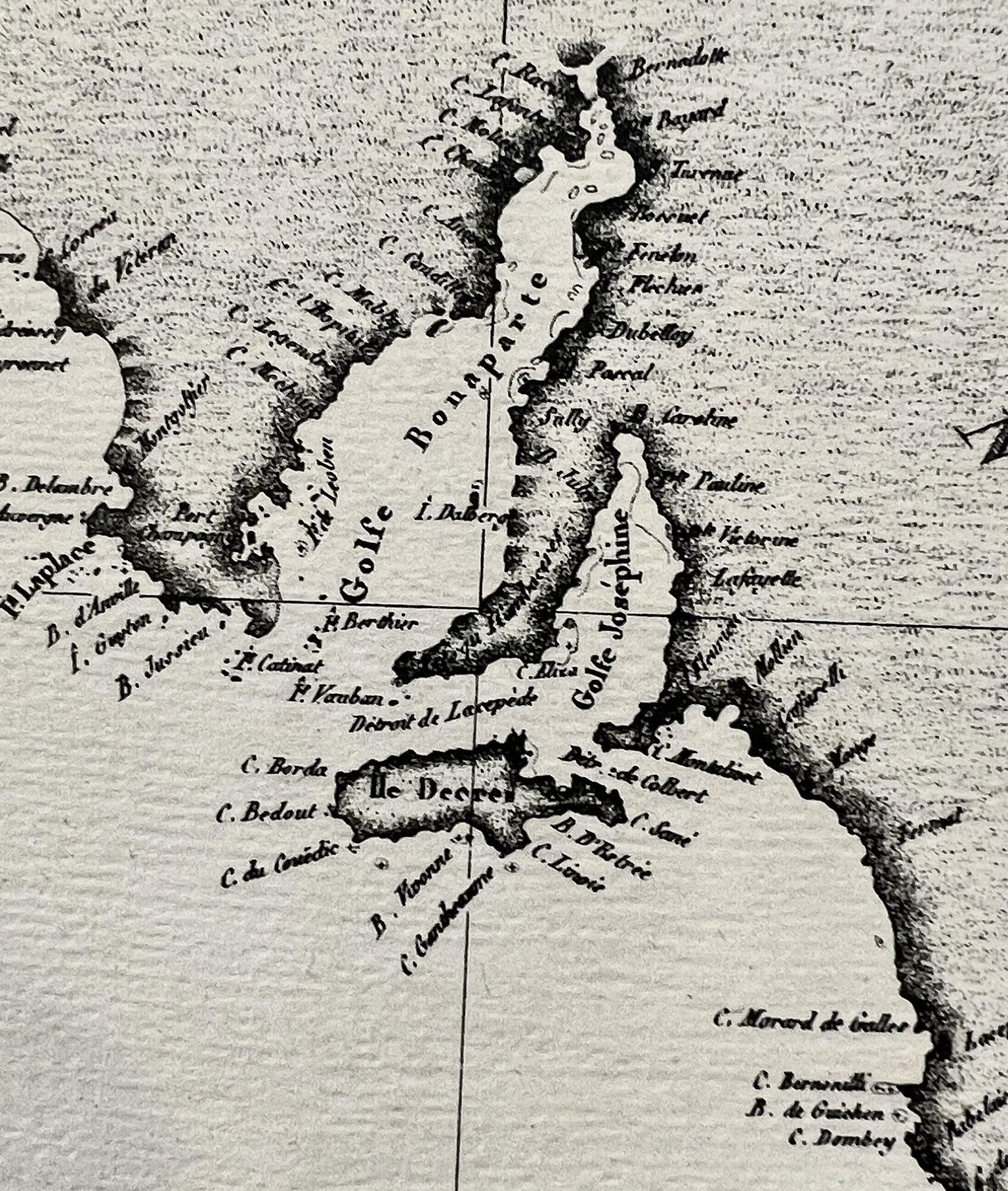

This interesting map shows just the top left of Australia,

As a footnote, I can’t resist posting a pair of rare hand coloured French ‘Australiana’ lithographs. They reflect the French interest in Australia – just days after the first British colonists arrived at Botany Bay in 1788, the French appeared, having travelled along the southern coast and then arriving right at the spot the British had chosen for their new colony. Coincidence? Not quite – Louis XVI was very interested in the idea of a colony in the South Seas, to compete with the British, and had instructed Lapérouse to report on the British actions on the Great Southern Land.

Of course, the Revolution soon took hold back in France – but science & exploration still carried on. In 1785, Jean François de Galaup, comte de Lapérouse was put in charge of a mission to the Pacific. The voyage of Lapérouse took a keen interest in the Great Southern Land, made keener by the colonising actions of their main competition, the British. They had arrived on the 18th January, after 252 days sailing from Britain. Lapérouse had been exploring for several years, but in one of those serendipity occurrences history throws up, arrived at the same point as the British just 6 days later! They stayed for six weeks, and then sailed off never to be seen again….

Nicolas Baudin was the next Frenchman to explore the South Pacific. He was selected by Napoleon in 1798 to explore the southern coast of Australia, or ‘New Holland’ as it was known. While the right-hand portion was the British colony of New South Wales, there was so much more promising land as-yet unclaimed. The tension between the French & the English is illustrated by the events at ‘Encounter Bay’, now in South Australia: Mathew Flinders was completing the first-ever complete navigation of Australia when he stumbled across Baudin’s ship heading the other direction… with the same intent! They cautiously approached, uncertain if they were meant to be enemies or allies, as when Bourdain had left France, they were at war. However, in the name of science, they met peacefully and proceeded on their way. While Baudin died on the way back to France, the charts made it and were published, including all the French names he had given to the features he mapped – ‘Napoleon’s Land’ features ‘Gulf de Napoleon’ next to ‘Gulf de Josephine’, for example. Unfortunately, Mathew Flinders had already mapped & named the same areas, giving them good British names like ‘Spencer Gulf’, names which were officially published a little later, and which remain to today.

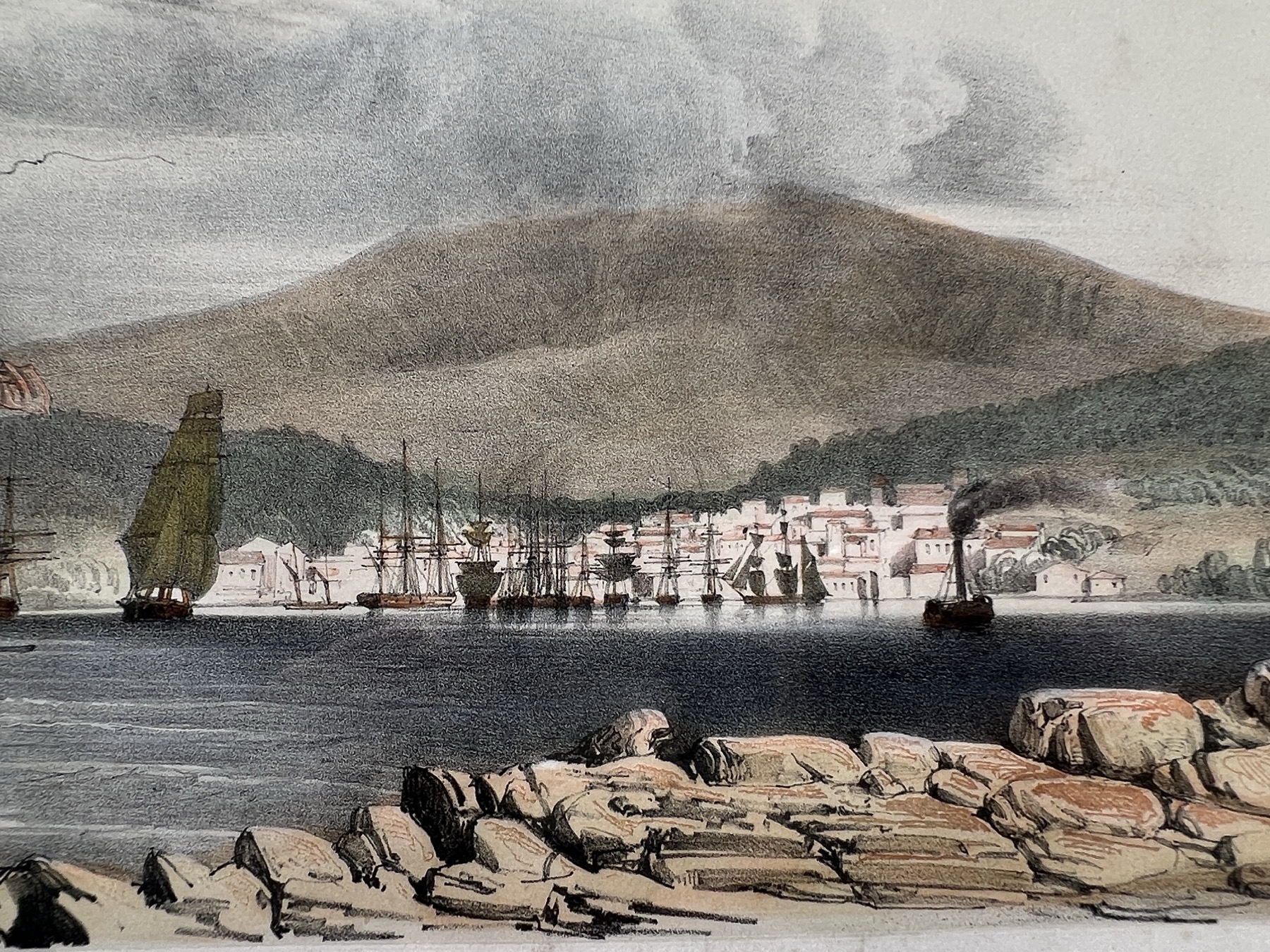

The fine French views of Hobart were published in 1833, the result of yet another French expedition to the region: confusingly, in a ship named in honour of the lost Lapérouse expedition: another Astrolabe, under Dumont D’Urville. He was instructed by the re-instated French monarch, Louis-Phillipe, to head south & claim the South Pole for France!

He left France on his first voyage in 1826, and was away for three years in total, visiting Hobart in 1827 to re-supply, when the sketches that were used for these lithographs were made. His voyage was published in ‘Voyage de la corvette “l’Astrolabe’, 1833, from which these come.

He was also responsible for solving the mystery of the disappearance of Lapérouse and his Astrolabe – which he did, discovering relics of the wreck on Vanikoro, in the Solomon Islands.

So Australia has a fair share of French History to celebrate!

Vive la France, tout le monde!

French Fresh stock for Bastille Day….

-

18th century French tin glaze apothecary jar, Ong. Styrax, c.1780$280.00 AUD

18th century French tin glaze apothecary jar, Ong. Styrax, c.1780$280.00 AUD -

Petite French Fauteuil, gold silk, Louis XV period c.1760$1,450.00 AUD

Petite French Fauteuil, gold silk, Louis XV period c.1760$1,450.00 AUD -

Vue d’Hobart-Town, 1833Sold

Vue d’Hobart-Town, 1833Sold -

Vue des Défrichemens, from ‘Voyage of the Astrolobe’ 1833Sold

Vue des Défrichemens, from ‘Voyage of the Astrolobe’ 1833Sold -

French Revolutionary print, la Tour d’Auvergne, published year ‘8’ – 1800$580.00 AUD

French Revolutionary print, la Tour d’Auvergne, published year ‘8’ – 1800$580.00 AUD -

Louis XV style fauteuil, early 20th centurySold

Louis XV style fauteuil, early 20th centurySold -

Louis XV style fauteuil, early 20th centurySold

Louis XV style fauteuil, early 20th centurySold -

Pair of French Fauteuils, Louis XV period circa 1765$2,950.00 AUD

Pair of French Fauteuils, Louis XV period circa 1765$2,950.00 AUD -

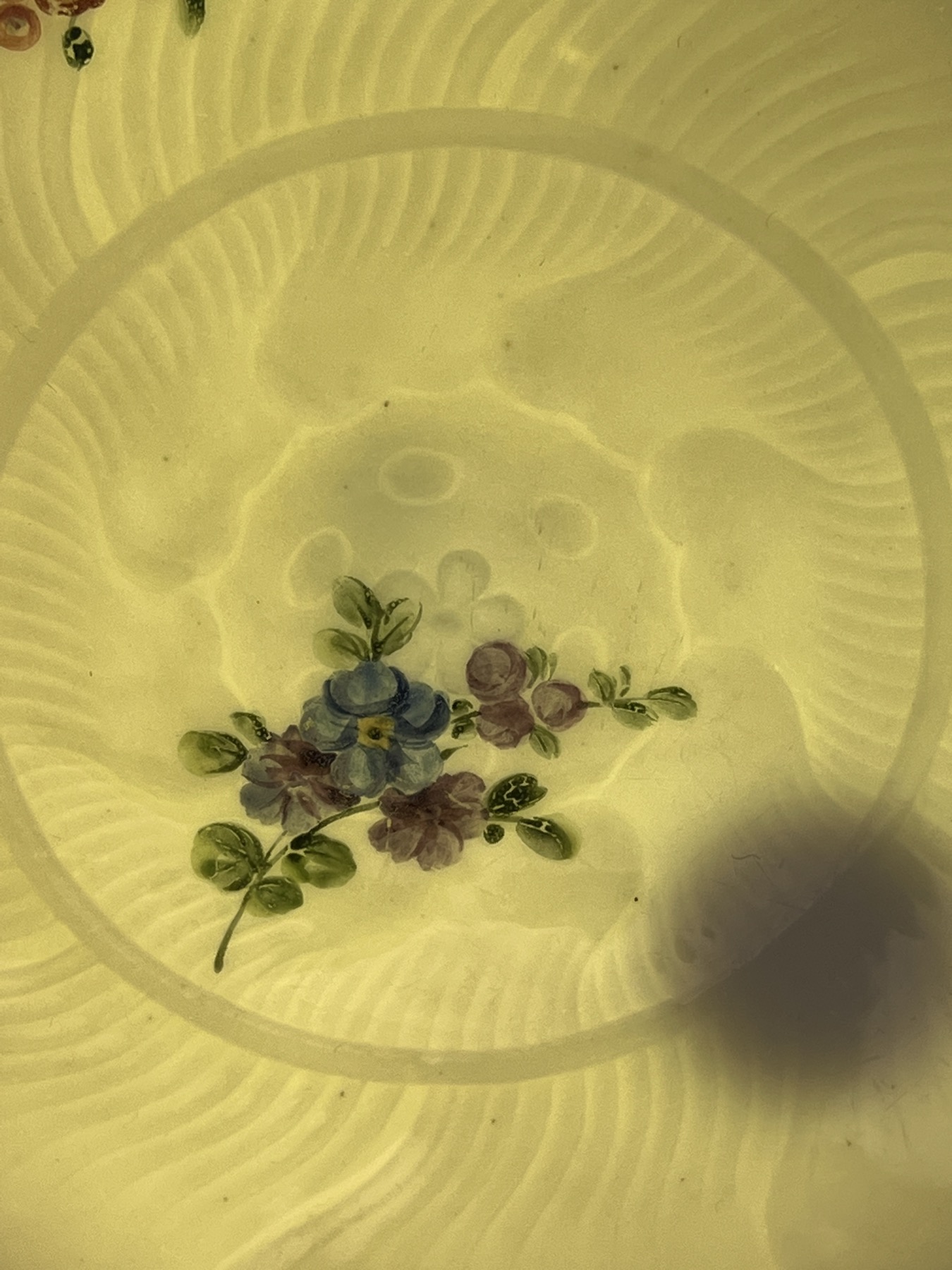

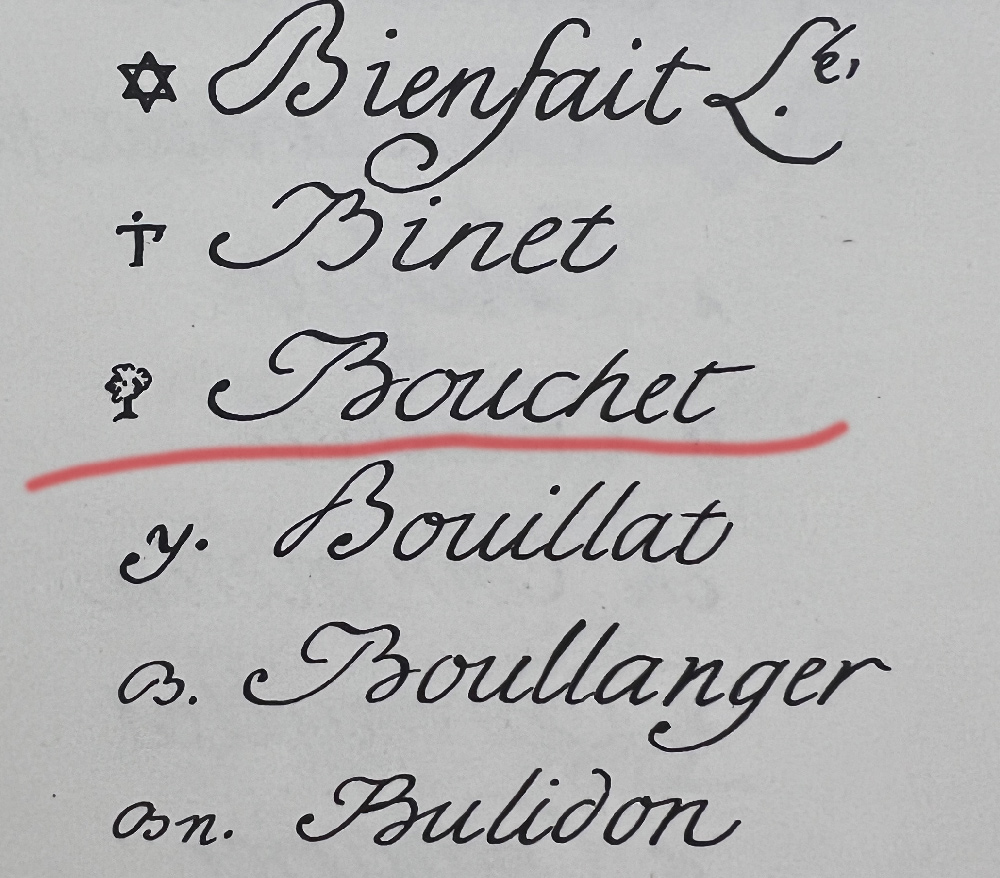

French yellow faience dish, Rococo form with flowers, attr. Montpellier c.1765$395.00 AUD

French yellow faience dish, Rococo form with flowers, attr. Montpellier c.1765$395.00 AUD -

Jean Baptiste PERRONNEAU (1716-83) -Pastel portrait of Jeanne-Marie Mallès, Dated 1751 Fresh Discovery!Sold

Jean Baptiste PERRONNEAU (1716-83) -Pastel portrait of Jeanne-Marie Mallès, Dated 1751 Fresh Discovery!Sold -

4 x French ormolu pelmet supports, 19thc.Sold

4 x French ormolu pelmet supports, 19thc.Sold -

French Revolutionary close-plated tankard, dated 1793$980.00 AUD

French Revolutionary close-plated tankard, dated 1793$980.00 AUD -

Small French Provincial buffet, Louis XV period$2,950.00 AUD

Small French Provincial buffet, Louis XV period$2,950.00 AUD -

Large French Fauteuil, Louis XIV C.1700$2,450.00 AUD

Large French Fauteuil, Louis XIV C.1700$2,450.00 AUD -

Large French Fauteuil, scroll arms, Louis XIV, Circa 1700$2,450.00 AUD

Large French Fauteuil, scroll arms, Louis XIV, Circa 1700$2,450.00 AUD -

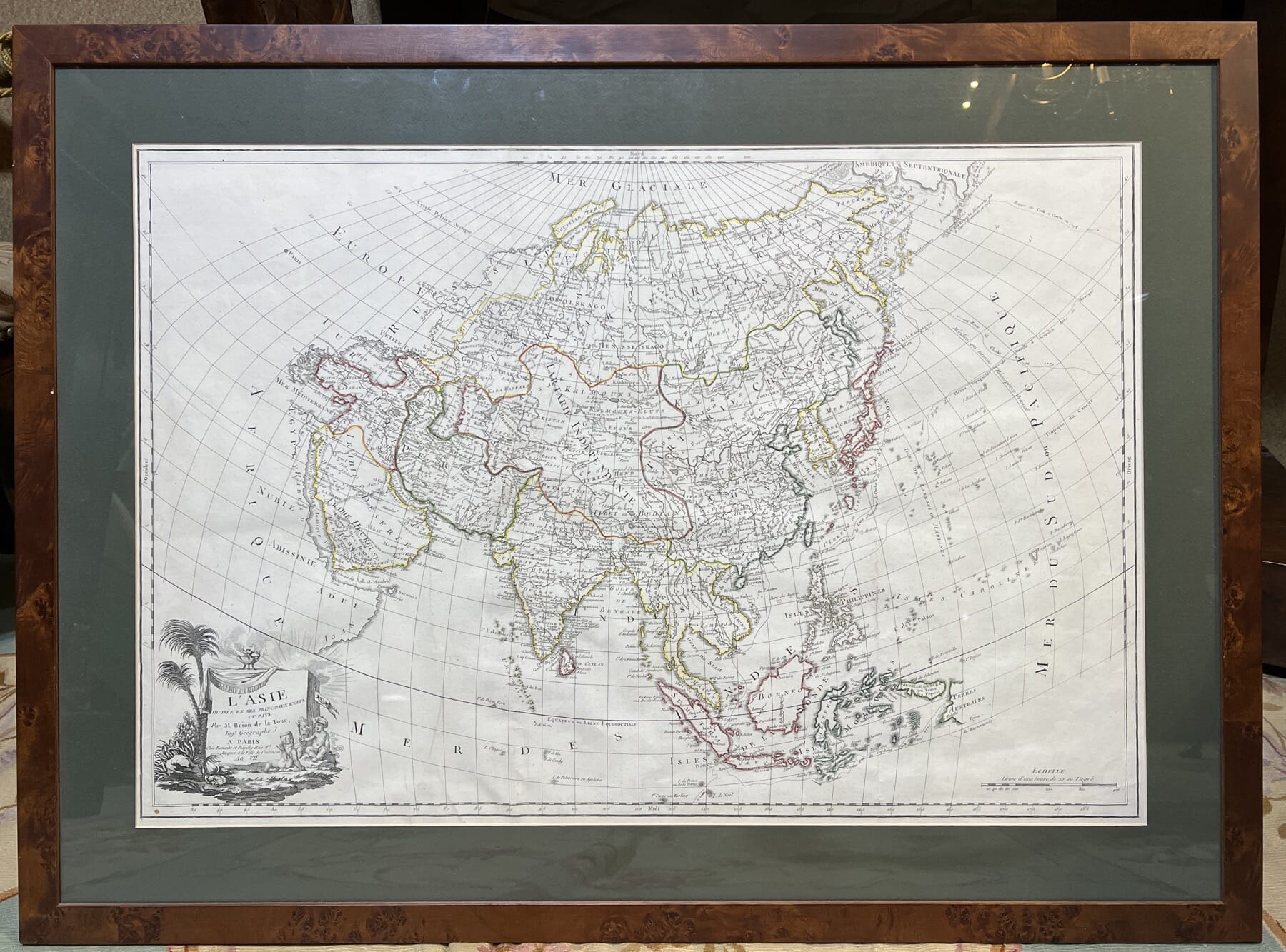

Large French map, Asia, by Lois Brion de la Tour, Paris, year VII (1798)$1,680.00 AUD

Large French map, Asia, by Lois Brion de la Tour, Paris, year VII (1798)$1,680.00 AUD -

Large French Faience jug, mid-18th century$680.00 AUD

Large French Faience jug, mid-18th century$680.00 AUD -

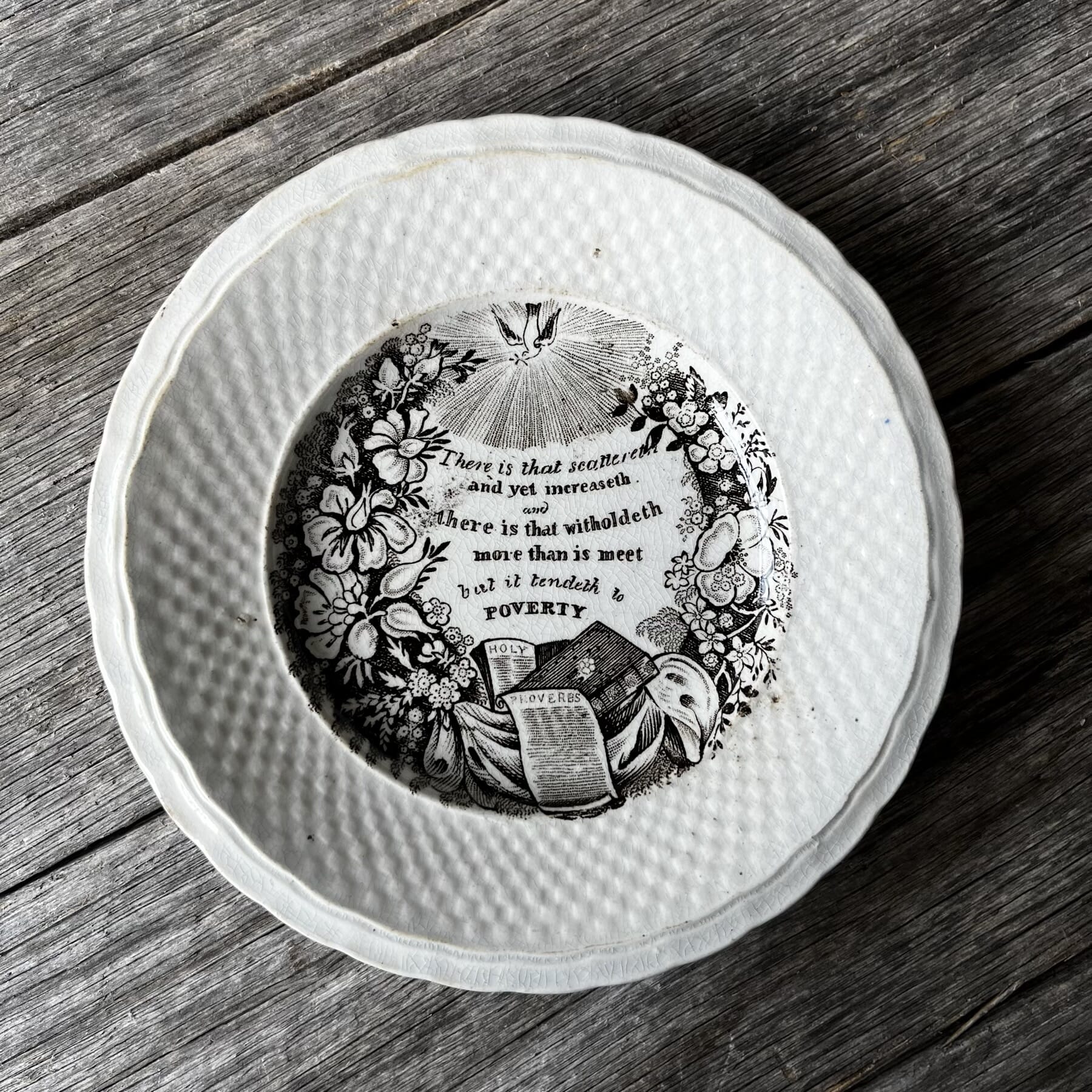

French creamware plate, Mademoiselle D’Artois print, c. 1825$235.00 AUD

French creamware plate, Mademoiselle D’Artois print, c. 1825$235.00 AUD -

Large French Provincial amoire, Louis XIII, mid-17th century$5,800.00 AUD

Large French Provincial amoire, Louis XIII, mid-17th century$5,800.00 AUD -

French fauteuil with faded red velvet upholstery and fringe, C. 1700$2,450.00 AUD

French fauteuil with faded red velvet upholstery and fringe, C. 1700$2,450.00 AUD -

French quill holder with figure of a seated lady, C. 1870.$95.00 AUD

French quill holder with figure of a seated lady, C. 1870.$95.00 AUD -

Head of Georges Danton, French Revolutionary faience jug, c. 1795$3,450.00 AUD

Head of Georges Danton, French Revolutionary faience jug, c. 1795$3,450.00 AUD

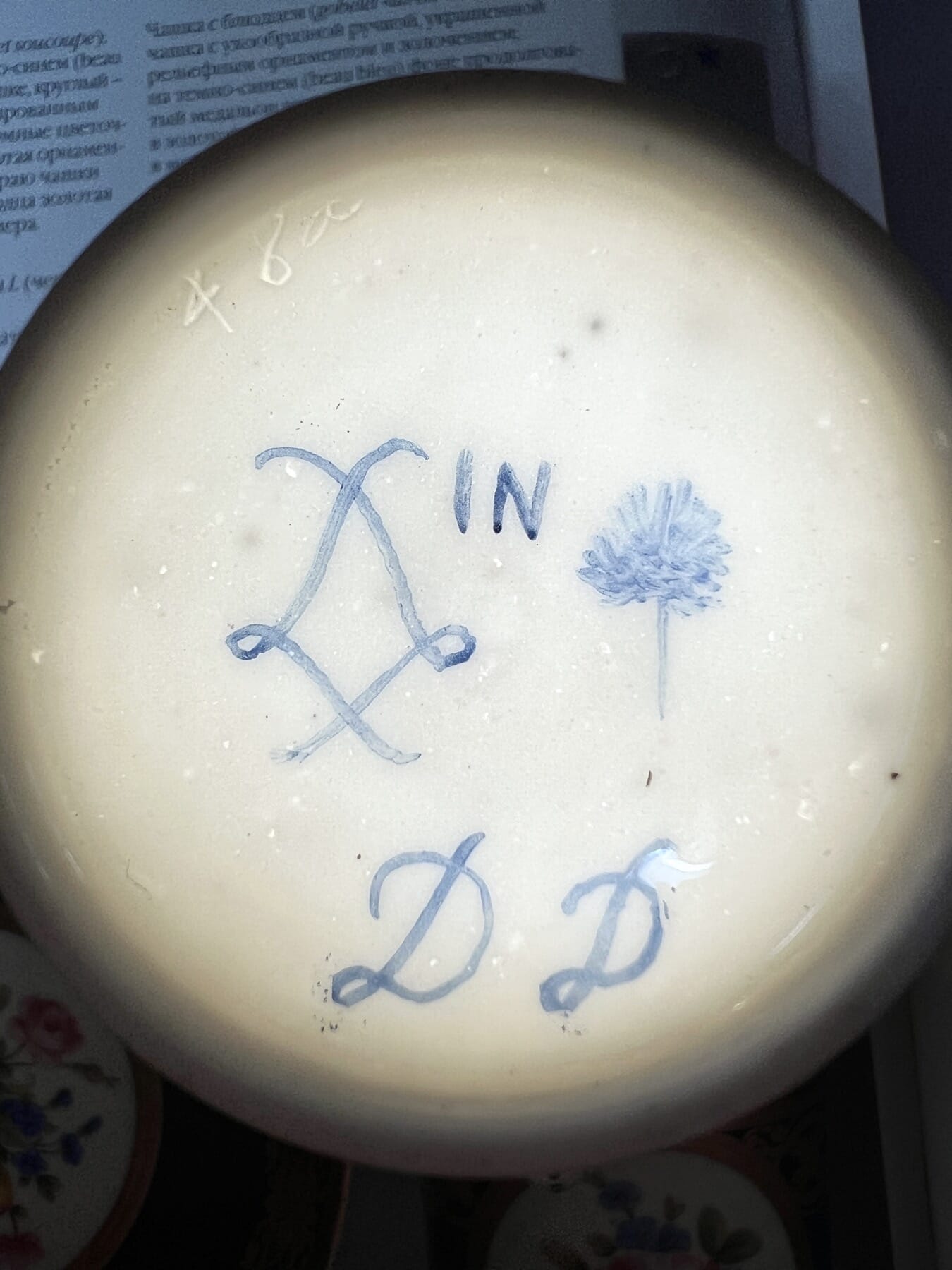

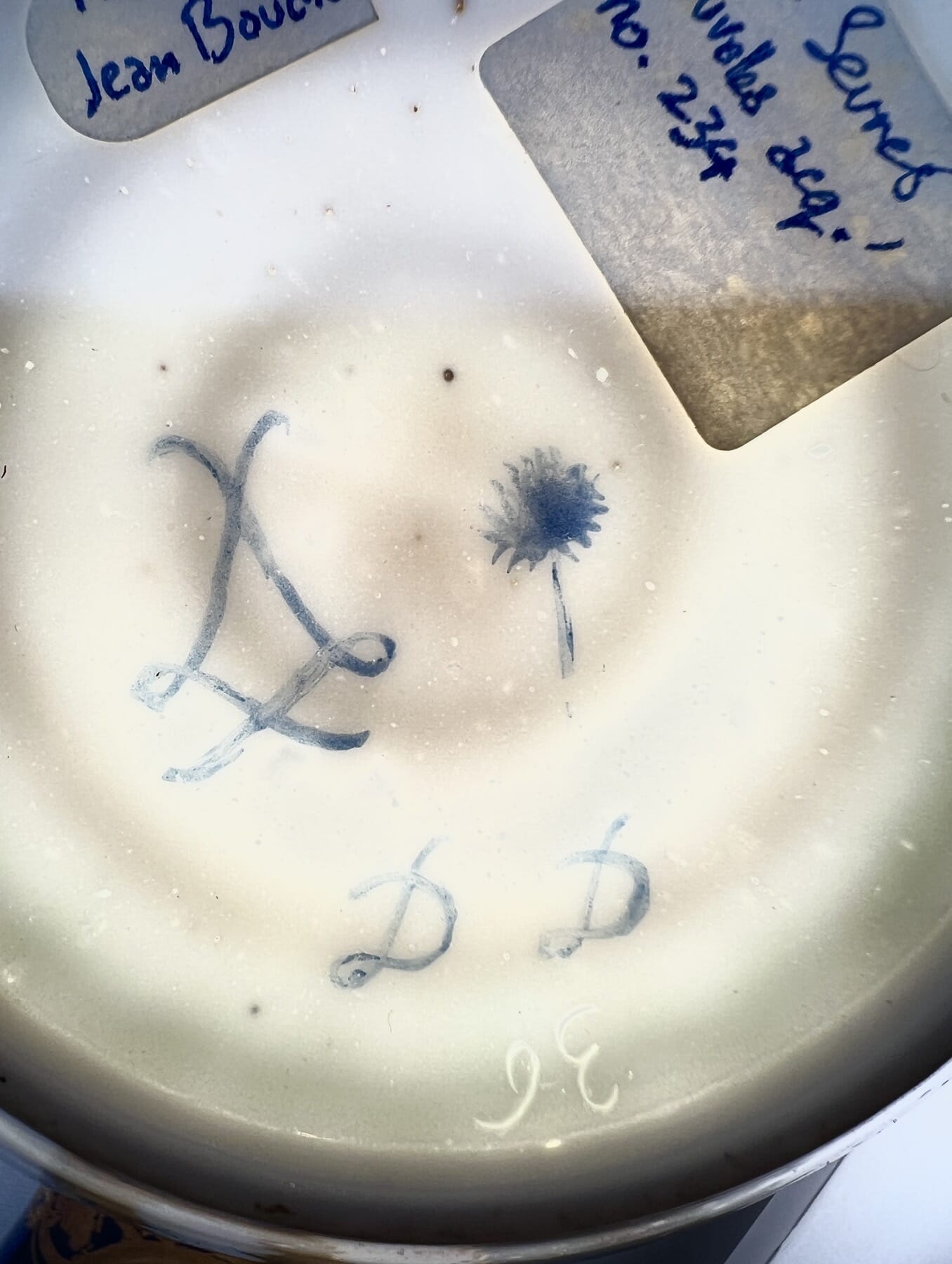

perhaps was not used much due to the issues we see on this cup & saucer: the blue tends to bead into clumps, and the thick yellow enamels shift in the heat of the enamel firings. While the yellow pigment had been a very early Sévres development, the tone seen here appears in the early 1780’s and is not repeated after the Revolution. There are a handful of specimens scattered around the globe in various collections, making this a most rare & desirable item.

perhaps was not used much due to the issues we see on this cup & saucer: the blue tends to bead into clumps, and the thick yellow enamels shift in the heat of the enamel firings. While the yellow pigment had been a very early Sévres development, the tone seen here appears in the early 1780’s and is not repeated after the Revolution. There are a handful of specimens scattered around the globe in various collections, making this a most rare & desirable item.