Welcome to our June 20th Fresh Stock.

Today, there’s a fine selection to browse, mostly pottery but with a few pieces of porcelain, and some Asian Antiques.

-

Staffordshire figures, Victoria & Albert with baby, c. 1840Sold

Staffordshire figures, Victoria & Albert with baby, c. 1840Sold -

Early Staffordshire figure, child with parrot, C. 1800$295.00 AUD

Early Staffordshire figure, child with parrot, C. 1800$295.00 AUD -

Large Ridgway blue printed ‘India Temple’ pattern, ‘Stone China’ comport C.1820Sold

Large Ridgway blue printed ‘India Temple’ pattern, ‘Stone China’ comport C.1820Sold -

Ridgway blue printed ‘India Temple’ pattern, ‘Stone China’ twin-handled tureen C.1820Sold

Ridgway blue printed ‘India Temple’ pattern, ‘Stone China’ twin-handled tureen C.1820Sold -

Ridgway blue printed ‘India Temple’ pattern, ‘Stone China’ plate with handles C.1820$125.00 AUD

Ridgway blue printed ‘India Temple’ pattern, ‘Stone China’ plate with handles C.1820$125.00 AUD -

Ridgway blue printed ‘India Temple’ pattern, ‘Stone China’ round plate with handles C.1820Sold

Ridgway blue printed ‘India Temple’ pattern, ‘Stone China’ round plate with handles C.1820Sold -

Minton blue printed ‘Chinese Marine’ ‘Opaque China’ plate C.1830Sold

Minton blue printed ‘Chinese Marine’ ‘Opaque China’ plate C.1830Sold -

Minton blue printed ‘Chinese Marine’ ‘Opaque China’ plate C.1830Sold

Minton blue printed ‘Chinese Marine’ ‘Opaque China’ plate C.1830Sold -

Minton blue printed ‘Chinese Marine’ ‘Opaque China’ Rectangular dish C.1830Sold

Minton blue printed ‘Chinese Marine’ ‘Opaque China’ Rectangular dish C.1830Sold -

Herend finely painted plate with Iris and other florals, c.1900Sold

Herend finely painted plate with Iris and other florals, c.1900Sold -

Pair of Staffordshire children on goats circa 1855Sold

Pair of Staffordshire children on goats circa 1855Sold -

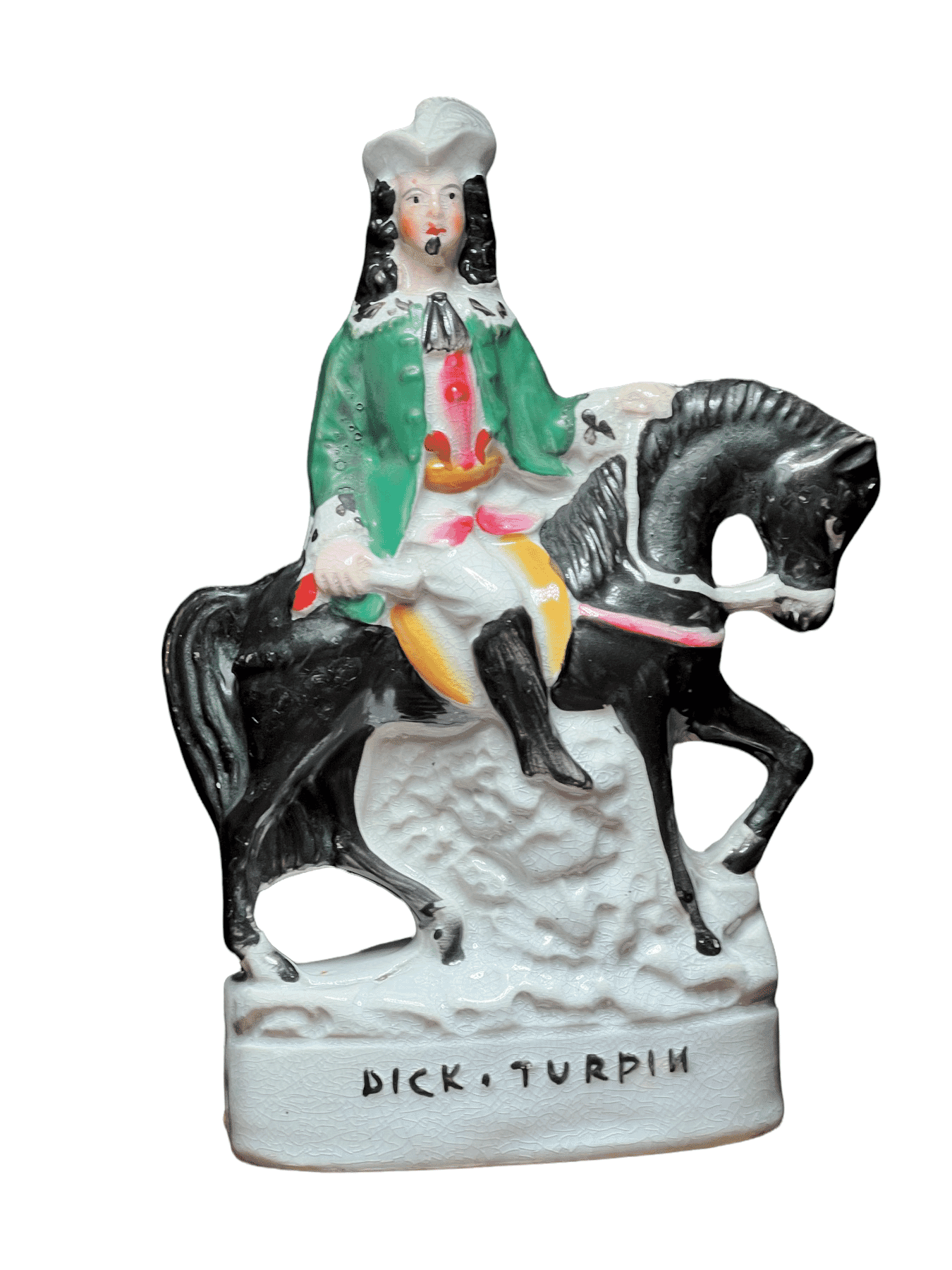

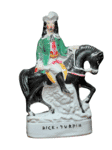

Staffordshire horse & rider figure, ‘Dick Turpin’, c. 1845Sold

Staffordshire horse & rider figure, ‘Dick Turpin’, c. 1845Sold -

Hartley Green & Co, Leeds, creamware plate, flower dec. c.1810$225.00 AUD

Hartley Green & Co, Leeds, creamware plate, flower dec. c.1810$225.00 AUD -

Pearlware tea canister, printed Chinoiserie island scene, c.1770$325.00 AUD

Pearlware tea canister, printed Chinoiserie island scene, c.1770$325.00 AUD -

Creamware plate with Chinoiserie scene, C.1770$325.00 AUD

Creamware plate with Chinoiserie scene, C.1770$325.00 AUD -

Victorian pewter straight-sided tankard, quart, circa 1850$65.00 AUD

Victorian pewter straight-sided tankard, quart, circa 1850$65.00 AUD -

Victorian pewter straight-sided tankard, quart, circa 1850$45.00 AUD

Victorian pewter straight-sided tankard, quart, circa 1850$45.00 AUD -

English creamware figure of a boy playing pipe, a dog & sheep at his feet, c. 1820$380.00 AUD

English creamware figure of a boy playing pipe, a dog & sheep at his feet, c. 1820$380.00 AUD -

Pair of German blue salt glazed vases in baroque style, c. 1880$280.00 AUD

Pair of German blue salt glazed vases in baroque style, c. 1880$280.00 AUD -

Liverpool pearlware plate with Chinoiserie in blue, C. 1780$480.00 AUD

Liverpool pearlware plate with Chinoiserie in blue, C. 1780$480.00 AUD -

English pearlware plate with Chinoiserie in blue, C. 1780.$480.00 AUD

English pearlware plate with Chinoiserie in blue, C. 1780.$480.00 AUD -

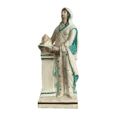

Staffordshire figure ‘Hope’ with anchor, c. 1800$395.00 AUD

Staffordshire figure ‘Hope’ with anchor, c. 1800$395.00 AUD -

Wedgwood drabware plate in sunflower pattern, c.1870.Sold

Wedgwood drabware plate in sunflower pattern, c.1870.Sold -

Early Staffordshire Pearlware figure, ‘Fire’, circa 1795Sold

Early Staffordshire Pearlware figure, ‘Fire’, circa 1795Sold -

Pair of creamware plates, Chinoiserie figure in garden, c. 1765Sold

Pair of creamware plates, Chinoiserie figure in garden, c. 1765Sold

Blue & White

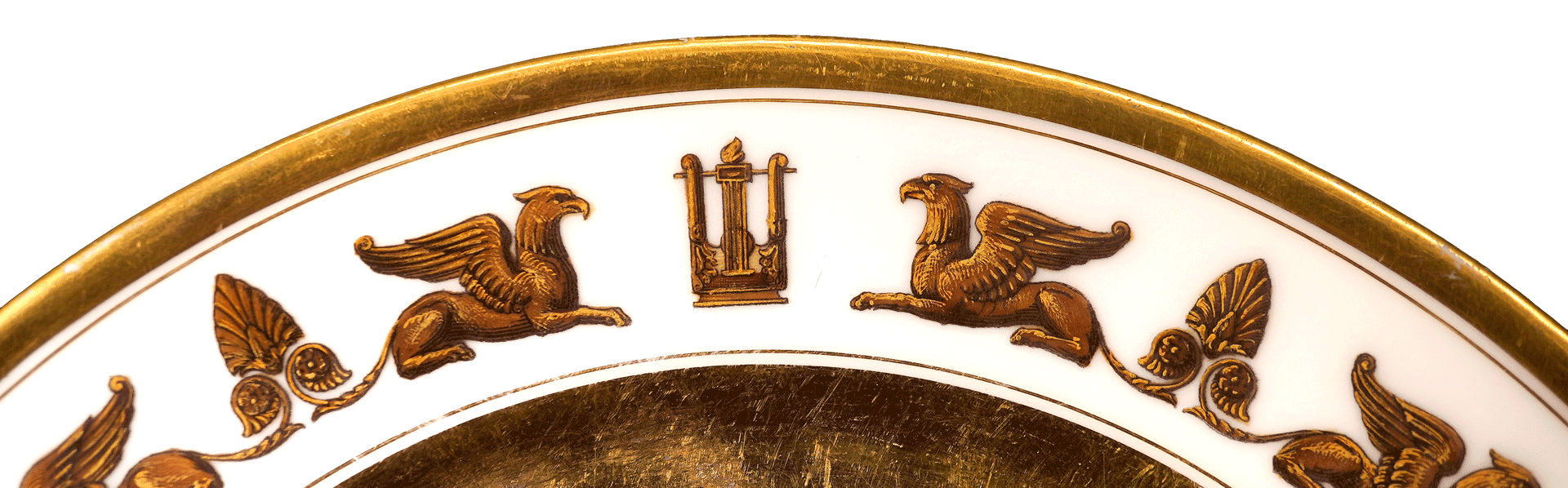

There’s a terrific group of printed English earthenware – at first, we thought it was a single service, the shapes and the patterns are so similar! One part is Ridgway’s ‘India Temple’ pattern, circa 1820. The other is Minton earthenware, and printed in blue with their ‘Chinese Marine’ pattern.

Earlier blue + white includes some interesting creamware plates, maker unknown, and some Liverpool ‘Pearlware’ plates. They make an interesting contrast: the Creamware lives up to its name, with the body having a distinct yellow tinge: the Pearlware, on the other hand, has had cobalt blue added to the lead glaze, which has the optical effect of making a pale colour look whiter. Where it pools along the footrim, there is a distinct blue tone, the required feature for classification as ‘Pearlware’.

Staffordshire Figures

We have some fresh Staffordshire to share with you, just before Paul gives his presentation on the subject at Valentine’s, Bendigo. Queen Victoria is very well represented – as a mother – and there’s a number of earlier 19th century figures as well.

See them here >>

What’s the story of the goats?

When Queen Victoria ascended the British throne in 1837, she received a fine pair of Tibetan goats as a present from the Shah of Persia. From these, a ‘Royal Goatherd’ was bred at Windsor. By the time the children were born, the goats were used to tow a miniature carriage just big enough for them to drive – and this caught the public’s imagination. These figures of children riding goats were obviously a talking point about the young royals and their childhood at Windsor.

This pair featuring in today’s Fresh Stock are fun – but different to the single example above in one important detail: they only have a single feather in their cap. The ‘Princess Royal’ above is identified by the three feathers in her hat, as in the ‘Prince of Wales’ symbol of three feathers.

Having single feathers may indicate thee are just what they appear to be – children riding goats! See this pair here >>

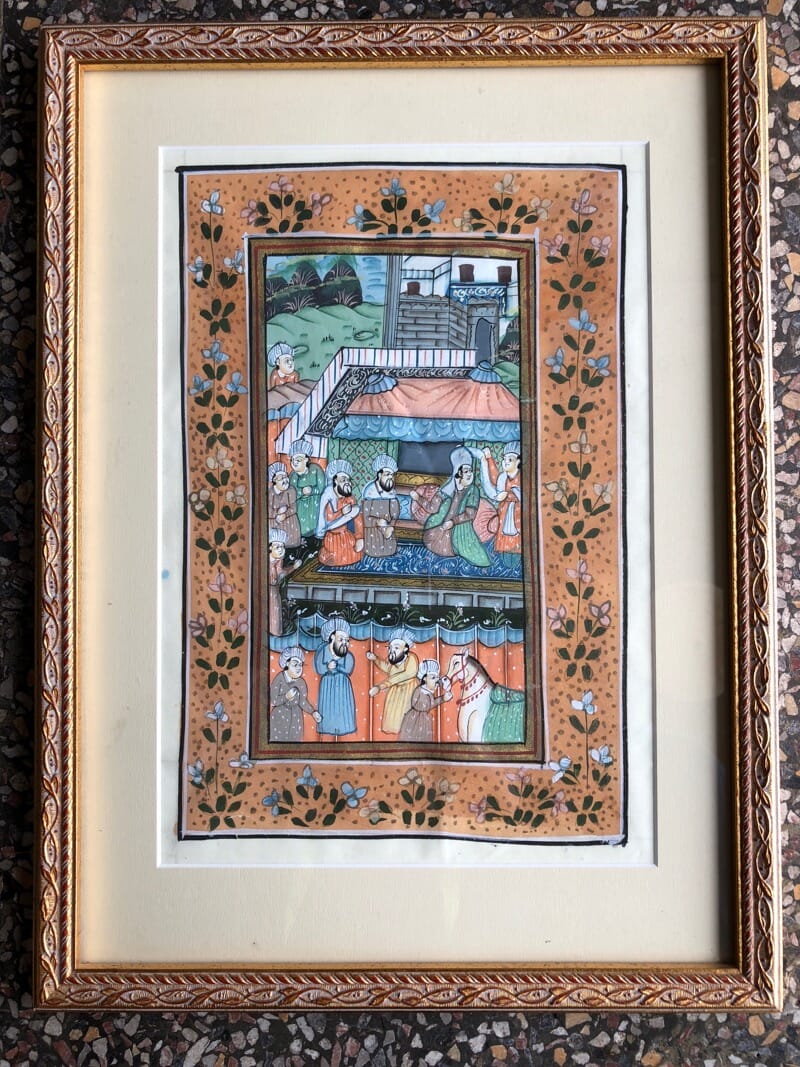

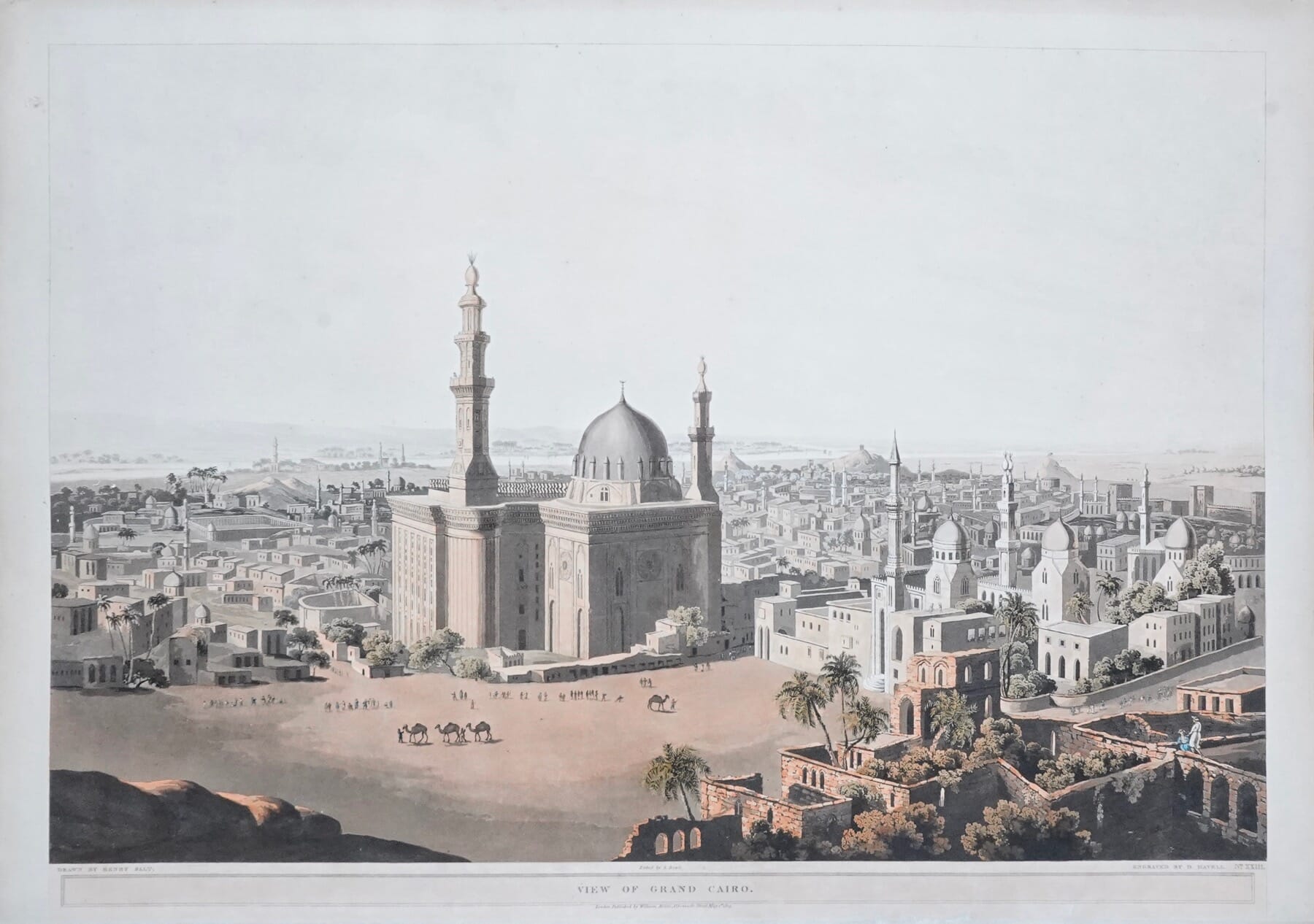

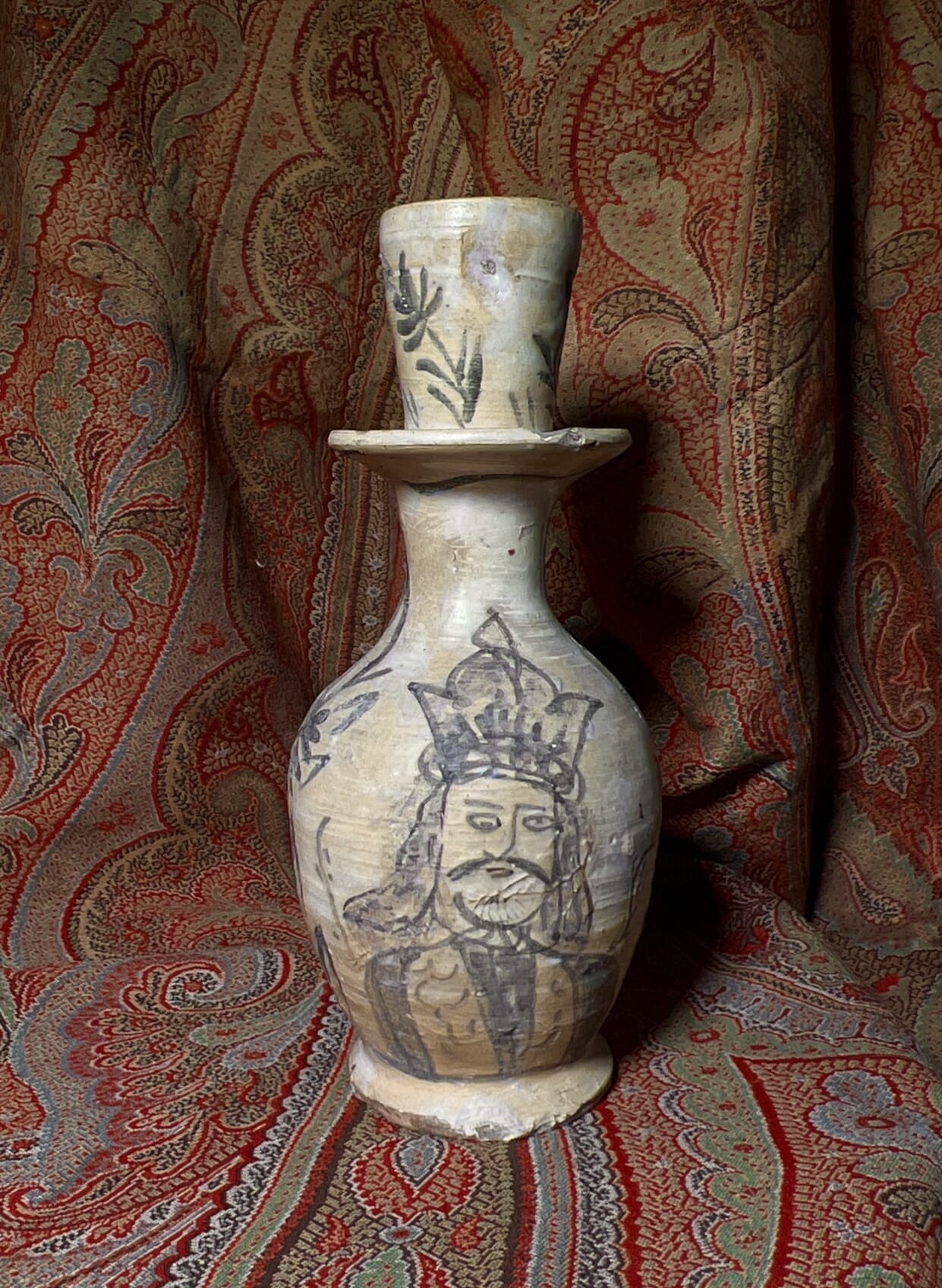

Asian Ceramics

There are some splendid fresh pieces of Chinese porcelain, mostly the ‘Nonya’ or Straights Chinese type – plus some other Asian items. There’s a superb collection of Ming and Kanxi just being prepared, expect it in the next few ‘Fresh Stock’ posts.

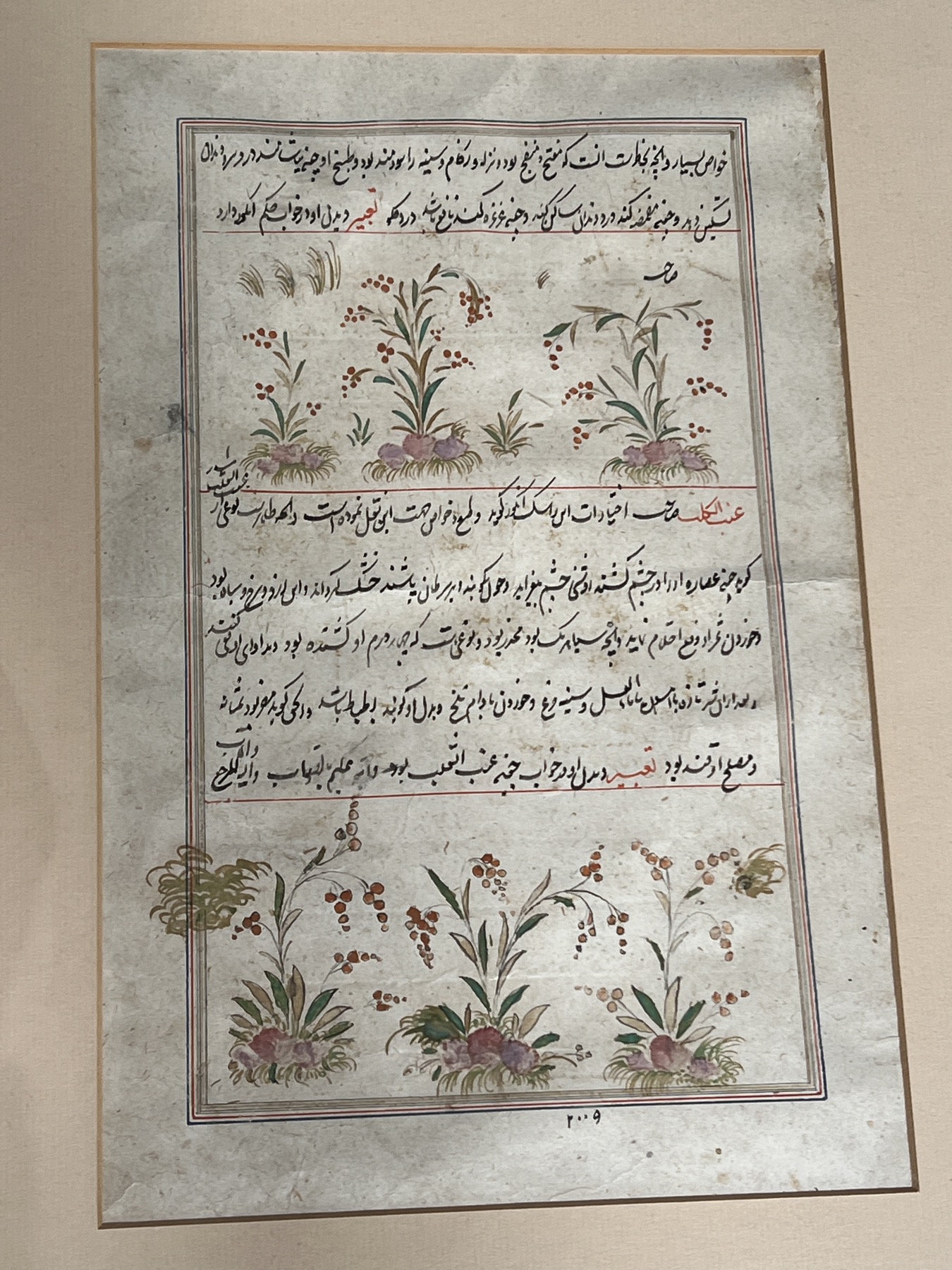

Botanical Illustrations

There’s a Fresh-to-stock group of superbly detailed watercolours, botanical studies for an unknown book. They would look wonderful framed & up on a wall as a group – ask for a price for the lot!

-

Original hand-painted botanical illustration – ‘Cinchona Succirubra’$45.00 AUD

Original hand-painted botanical illustration – ‘Cinchona Succirubra’$45.00 AUD -

Original hand-painted botanical illustration -Passionfruit, ‘Passiflora edulis’Sold

Original hand-painted botanical illustration -Passionfruit, ‘Passiflora edulis’Sold -

Original hand-painted botanical illustration -Sugarcane, ‘Saccharium Officinarum’$55.00 AUD

Original hand-painted botanical illustration -Sugarcane, ‘Saccharium Officinarum’$55.00 AUD -

Original hand-painted botanical illustration – Chillies with flower$65.00 AUD

Original hand-painted botanical illustration – Chillies with flower$65.00 AUD -

Original hand-painted botanical illustration – Kumquat with leaves ‘ Fortunella Margarita’$65.00 AUD

Original hand-painted botanical illustration – Kumquat with leaves ‘ Fortunella Margarita’$65.00 AUD -

Original hand-painted botanical illustration – vanilla vine & podsSold

Original hand-painted botanical illustration – vanilla vine & podsSold -

Original hand-painted botanical illustration – Pomelo ‘C. Grandis’Sold

Original hand-painted botanical illustration – Pomelo ‘C. Grandis’Sold -

Original hand-painted botanical illustration – Citron, ‘Citrus Medica’$65.00 AUD

Original hand-painted botanical illustration – Citron, ‘Citrus Medica’$65.00 AUD -

Original hand-painted botanical illustration -Cotton, ‘Gossypium Hirsita’$45.00 AUD

Original hand-painted botanical illustration -Cotton, ‘Gossypium Hirsita’$45.00 AUD -

Original hand-painted botanical illustration – Roselle, “Hibiscus Sabdarifta’$45.00 AUD

Original hand-painted botanical illustration – Roselle, “Hibiscus Sabdarifta’$45.00 AUD